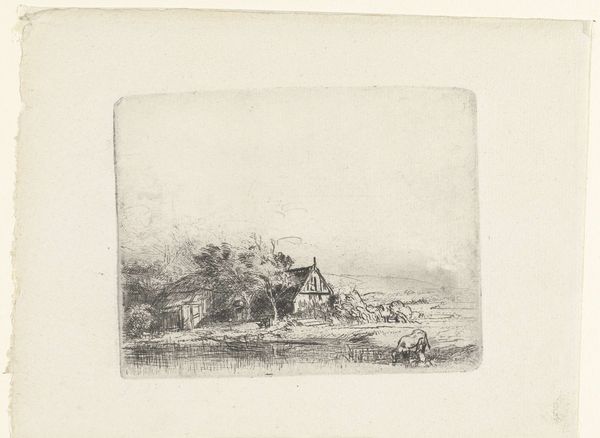

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have a delicate pencil sketch held at the Rijksmuseum titled "Landschap met drinkende koe," or "Landscape with a Drinking Cow," attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, possibly dating anywhere from 1648 to 1808. Editor: It’s incredibly subtle, almost ethereal. There’s a peacefulness here, a sense of rural life continuing regardless of the larger social struggles brewing in that era. It makes you wonder who owned this land. Curator: Absolutely, and that connects with much of the landscape art of the Dutch Golden Age. On the one hand, this style signifies growing urbanization and a new merchant class able to purchase real estate; on the other hand, as we can discern in the drawing, there's an idealization of nature as unspoiled, tranquil, a symbol of order. Editor: I'd argue that the depiction of the cow is equally powerful. It serves as a sort of "every animal" figure, an emblem of agrarian labor and prosperity—a visual shorthand that evokes the deep bonds between people and the land, though often masking inequalities inherent in land ownership. This could almost be an Arcadian image if not for its sketchy rawness, resisting a perfectly beautified interpretation of nature. Curator: Exactly. The very nature of pencil—its quick, fluid potentiality—allows for multiple meanings. A highly-rendered cow might suggest prosperity outright, whereas this one appears quite common, not stylized at all. In many ways, that reflects a shifting symbolic landscape in that era. Traditional symbols connected with the nobility are starting to be replaced by those depicting the working class. Editor: It's precisely that ambivalence I find fascinating. The work acknowledges the beauty and the sustenance of the natural world, yet whispers about who benefits from that labor. A contemporary artist might explore similar terrain, reflecting our equally complex relationship with nature, given ongoing ecological crises and class structures. Curator: The way the thatched roofs mimic the slopes of the fields...a reflection of a worldview that saw humans and nature coexisting, co-evolving within a greater order. Editor: Perhaps the drawing urges us to engage with the pastoral in new ways—a sort of resistance to the oversimplified readings of such scenes in our historical memory, where romanticizing nature often comes at the expense of understanding the realities of labor. Curator: Ultimately, its power lies in asking these questions across the ages.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.