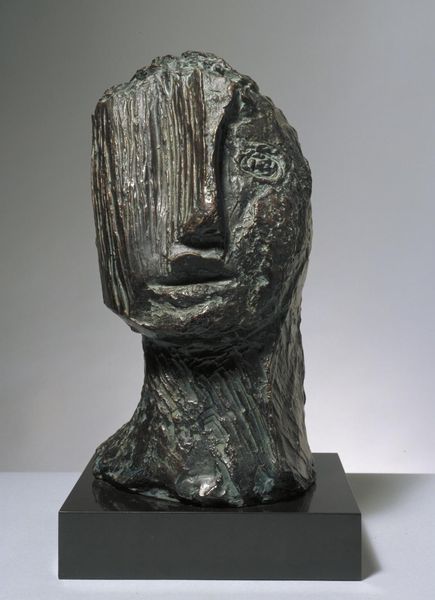

Dimensions: 26.5 x 26.5 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us is "Lament" by Käthe Kollwitz, crafted from bronze, possibly between 1938 and 1960. The work resides here at the Städel Museum. Editor: The immediate impression is striking, a dense feeling of grief. The raw texture of the bronze lends a powerful sense of pain and resignation. Curator: Precisely. Kollwitz's process here is particularly important. We see evidence of her direct engagement with the material, almost a battle with the bronze to express the depth of sorrow. It resists easy narrative; rather it emphasizes the laborious aspect of mourning itself. The act of physically working the bronze echoes the arduous internal labor of grief. Editor: And it's crucial to remember Kollwitz’s biography here. The loss of her son Peter in World War I haunted her life and her art. This sculpture transcends personal tragedy, though. It becomes an icon of universal suffering, reflecting the impact of war and social injustice on individuals and families, specifically reflecting on working class women of her time, rendered invisible by mainstream patriarchal narratives. Curator: Absolutely. The choice of bronze further reinforces these ideas. Its durability speaks to the enduring nature of sorrow but it's also rooted in the availability of this material to her in the face of post-war austerity, forcing her to be resourceful and creative. It is rough, unlike refined materials often favored in sculptures, which shifts our attention from artistic polish to raw expression. Editor: I agree. Furthermore, that rough handling visually echoes the social context of profound loss after both World Wars. Kollwitz created multiple versions of grieving mother figures—I interpret this one as representative of a broader community's collective lament. A powerful statement on the human cost of conflict that gives voice to historically under-represented feelings of anguish. Curator: Yes, thinking about the casting process brings new light. Did Kollwitz use the lost-wax method? Did she have assistants? These elements bring in the narrative of artistic production—a confluence of effort and choice, challenging us to see art-making within wider systems. Editor: The act of creating, as you point out, a deliberate disruption of normalized forgetfulness. It encourages a sustained engagement with historical pain that can inform current movements for peace and social justice, too. Curator: Ultimately, this sculpture remains a profound object lesson in transforming trauma into art, inviting reflection and empathy through meticulous labor. Editor: Indeed. By grappling with her personal sorrow, Kollwitz crafted an enduring, complex reminder that art is essential for collective remembrance and transformation.

Comments

stadelmuseum about 2 years ago

⋮

This is the mute lament of an artist, perpetuated in bronze. The image speaks of pain, grief and incomprehension: the overlarge, powerful hands are placed protectively over the mouth and eye, as if wanting to no longer be compelled to see the terrible events, or to suppress a scream. With this relief created during the Nazi dictatorship, Kollwitz recalls her artist friend Ernst Barlach, who had died in 1938 and who was ostracised like her. As early as 1920 she had formulated her artistic task timelessly and with universal validity: "I shall give voice to the suffering of man, which never ceases."

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.