![(13) [Persepolis] by Luigi Pesce](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2NhMWUwYTYxLTUzYWMtNDMwYy1hMjg2LTA5MjdiZmU2YThjYS9jYTFlMGE2MS01M2FjLTQzMGMtYTI4Ni0wOTI3YmZlNmE4Y2FfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

carving, photography, architecture

#

carving

#

landscape

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

carved into stone

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

arch

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

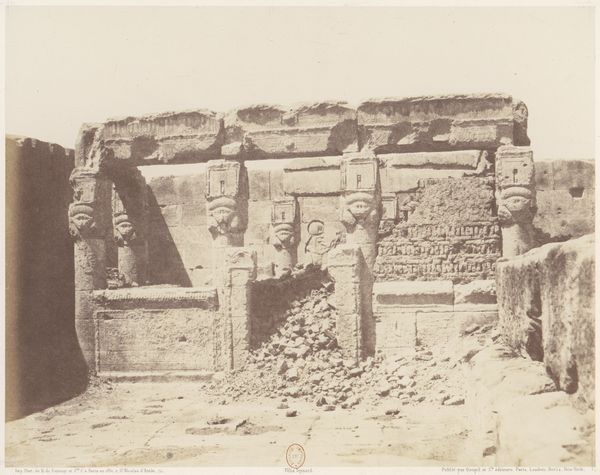

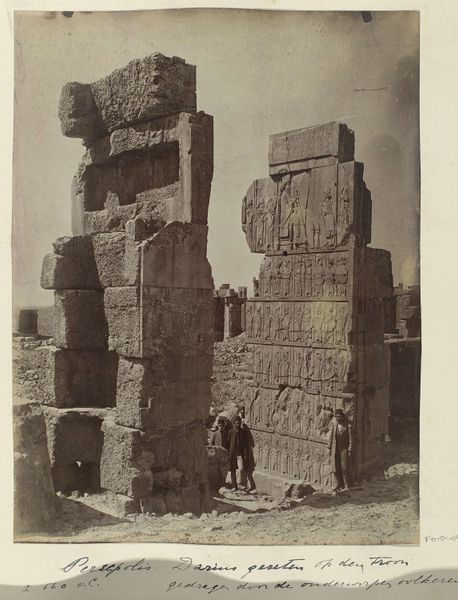

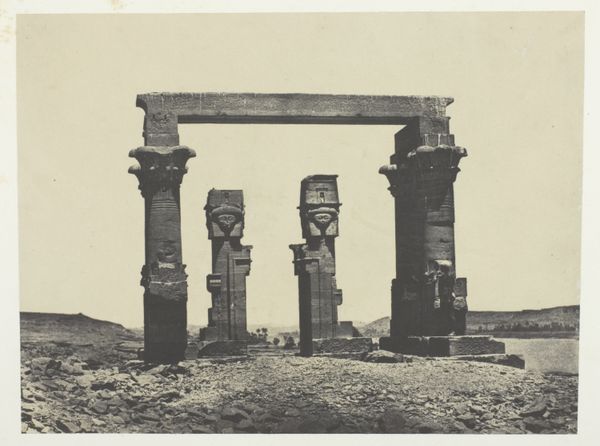

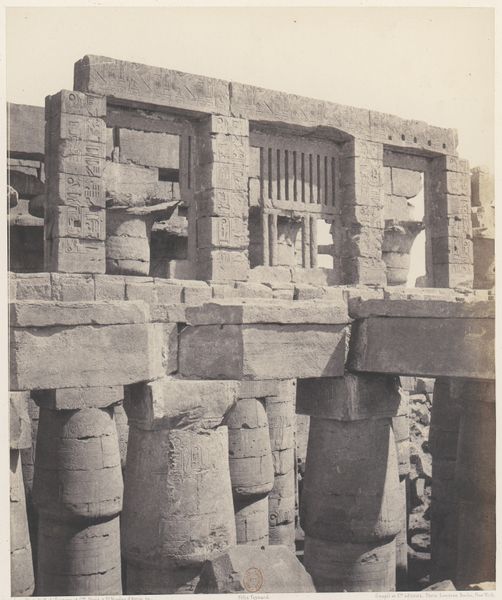

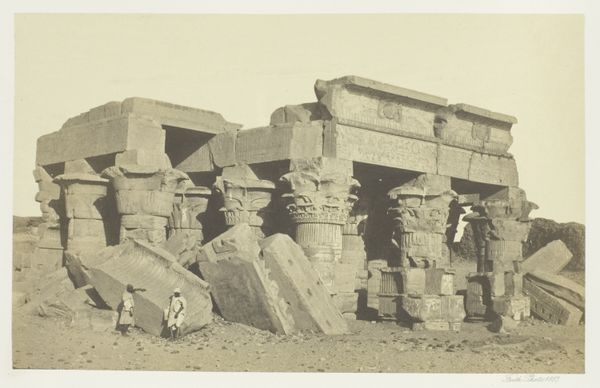

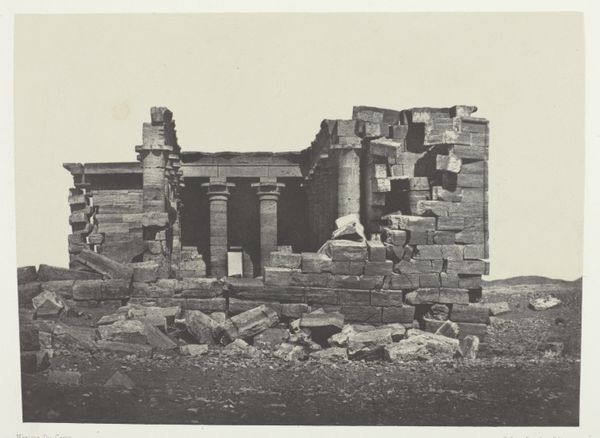

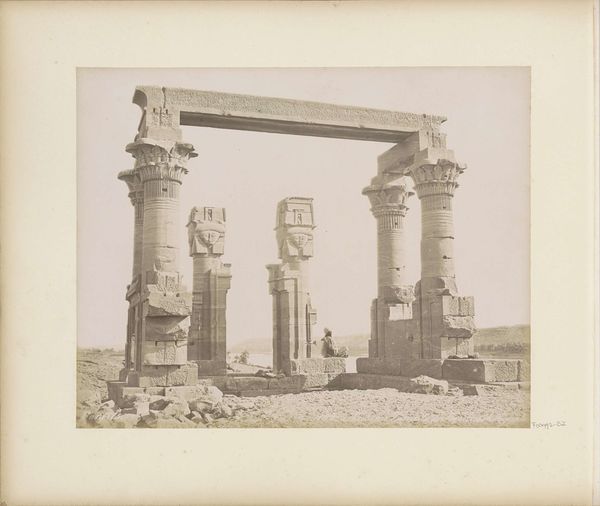

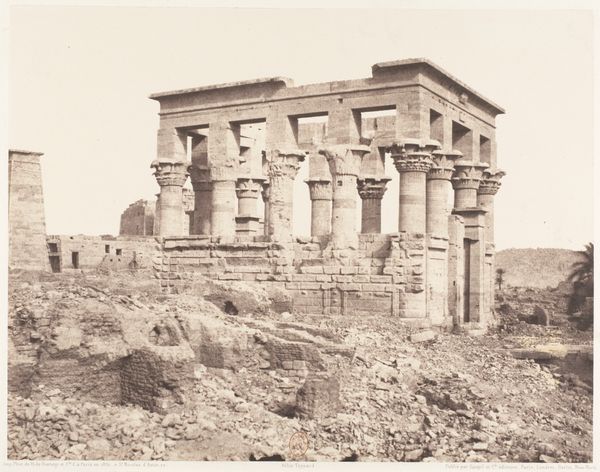

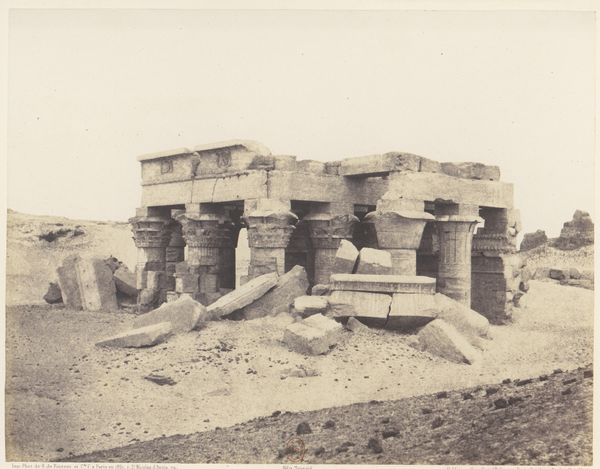

Editor: Here we have Luigi Pesce's photograph "(13) [Persepolis]" taken sometime between 1840 and 1869. The image is, well, arresting! A stark, sepia-toned view of what looks like ancient ruins, immense stone carvings rising from a landscape littered with rubble. What strikes me is the way photography, a relatively new medium at the time, is being used to document such an ancient site. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: This photograph speaks volumes about the burgeoning field of archaeology and its intersection with colonial interests in the mid-19th century. Photography offered a seemingly objective means of documenting historical sites like Persepolis. However, the choice of perspective, lighting, and what to include or exclude, always involves subjective decisions that reflect the photographer’s – and, by extension, society’s – biases. Consider how this image might have been used to bolster European claims of cultural superiority by highlighting the 'fallen glory' of a non-Western civilization. Editor: So, you're suggesting that this photograph isn't just a neutral record, but a statement? A form of visual rhetoric? Curator: Precisely! How was it circulated? Who was the intended audience? These details are crucial. Were these images meant to educate the public back home, or serve as trophies for wealthy collectors? These factors reveal a great deal about the socio-political forces shaping the image’s production and reception. Early photography was rarely about simple documentation; it was often deeply entwined with power dynamics. Think of who funded Pesce’s expedition and for what reasons. Editor: It's fascinating to consider the layered meanings embedded in what appears to be a straightforward image. It makes you wonder about the purpose behind archiving such records and who gets to tell these stories. Curator: Indeed. It urges us to analyze the narratives that photographs construct, and the institutional contexts in which these narratives gain authority. We should always be aware of photography's power in shaping how we perceive history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.