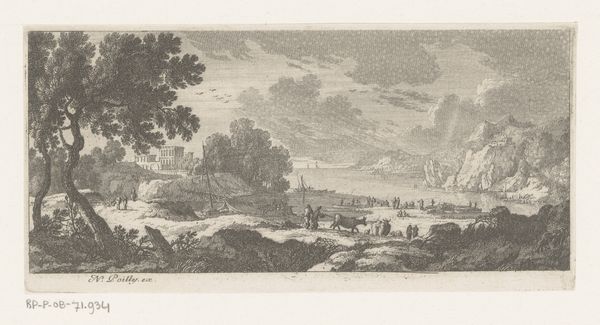

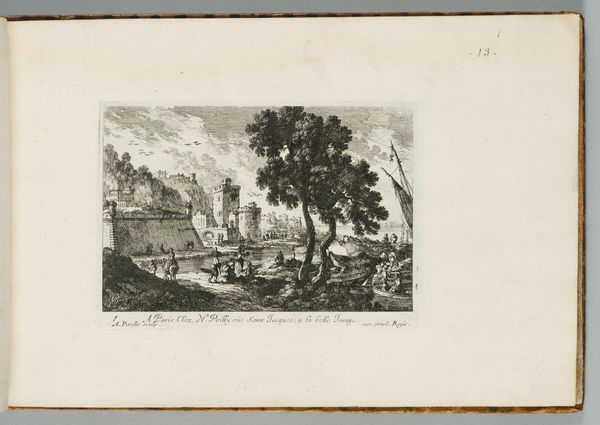

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 104 mm, width 209 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This etching, entitled "Ruïne op kade bij zee" or "Ruin on a Quay by the Sea," is attributed to Nicolas Perelle and dates sometime between 1613 and 1666. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: My immediate impression is of decay and a slightly unsettling tranquility. The architectural ruins juxtaposed with everyday dockside activities…it creates a poignant sense of transience, doesn't it? Curator: Absolutely. The contrast is striking. Perelle has created this landscape, really a city-scape, through etching, a printmaking process reliant on acid to cut into the metal plate, holding ink to create the lines on paper. You can almost feel the pressure of the printmaking process at play, a pressure like the socio-economic conditions shaping the landscape that Perelle so neatly captures. Editor: That's a great point about the process informing the product! And think about the context in which such prints circulated. These weren’t precious, unique objects necessarily, but rather relatively mass-produced images. How do we consider its distribution, consumption and impact on viewers accustomed to seeing their world reflected through this lens? It serves almost like early modern mass media! Curator: Precisely. These images served a very public role. How they depict the urban landscape and social interactions tells us a great deal about the prevailing ideologies and perspectives of that period. Was this ruin a picturesque element to be admired, or did it represent societal failings, failures of infrastructure? Editor: I'd argue that it probably served both purposes! On the one hand, we romanticize ruins. On the other hand, you are also documenting a moment, recording aspects of social life. How do the figures use that space? It adds nuance to the idealized ruin, anchoring the image within its own historical context, prompting reflection on how places evolve. Curator: It is thought-provoking how Perelle weaves those layers together through line, texture, and form. We often impose categories-- high art or craft--when what we have here is something fluid, dependent upon the artist's skills as much as the viewer's social positioning and the circulation context for its overall historical meaning. Editor: A great reminder to look at art not just as aesthetic objects, but as dynamic documents shaped by social processes, which helps us grasp the complexities inherent in interpreting such historical prints. Curator: Yes, it invites you to re-evaluate historical records. It challenges the rigid categorization and the power dynamics, if you look closely enough.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.