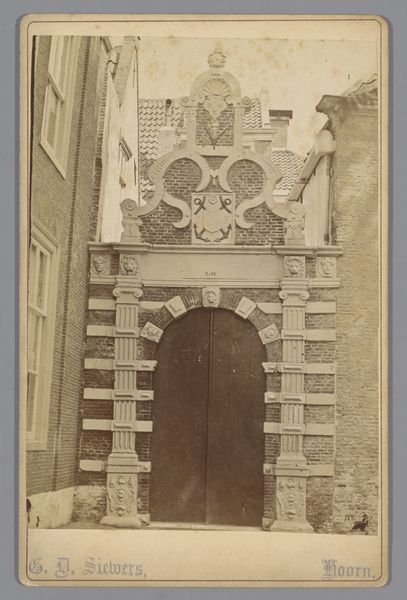

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

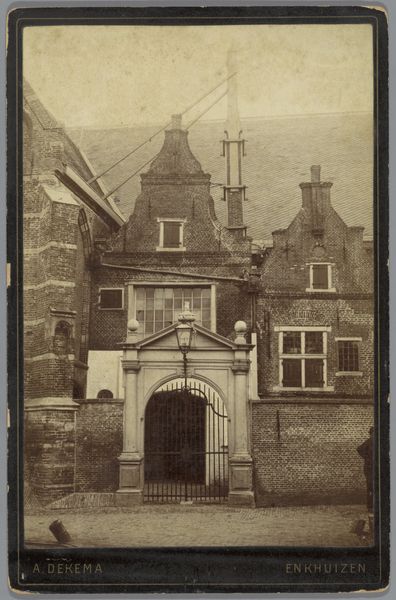

Editor: This is "Oosterpoort te Hoorn," a photograph by Gerrit Dirk Siewers, probably taken between 1855 and 1890. It’s quite a stark image of a city gate, isn't it? Almost feels like a stage set. What catches your eye when you look at this piece? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the process of creating this image. As a daguerreotype and a print, the layering of techniques, the precise moment of capturing the gate contrasted with the later act of reproduction - what does this tension between automation and manual work tell us? Consider the social context; this isn't just a gate, it’s a symbol of a city's power and history. The gate represents controlled access, a tangible boundary. What kind of statement do you think Siewers was trying to make through its representation in this way? Editor: That's a great question! Perhaps about the changing face of the city itself? I mean, photography democratized image-making, right? And that coincides with changes in power structures... Curator: Exactly! It prompts questions about labor. Who built this gate? What materials were used and from where were those sourced? What social class benefited from this construction? And what class might have labored? The material existence of the photograph then extends outwards towards the larger circumstances of life in this period. It becomes evidence. The photograph, this specific object we see, gives us a trace of past labor. It challenges romantic views and calls attention to underlying materials. Editor: So, the romantic style listed in the description becomes almost ironic in a way? It uses romantic visual language to show a very real place shaped by equally real, sometimes harsh, social forces. Curator: Precisely. Seeing the labor that constructed the gate forces one to face the realities beyond romanticization. Now, can you view other "romantic" artwork critically, searching for underlying conditions that contributed to its creation? Editor: I think so. I'll definitely look closer at materiality and labor in future works I study. It offers a much richer, albeit more complicated, understanding. Curator: Indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.