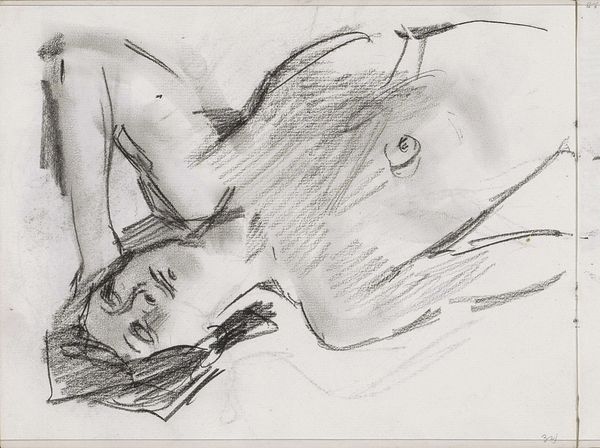

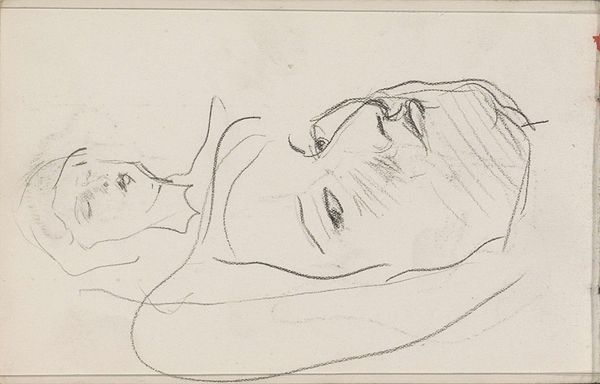

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

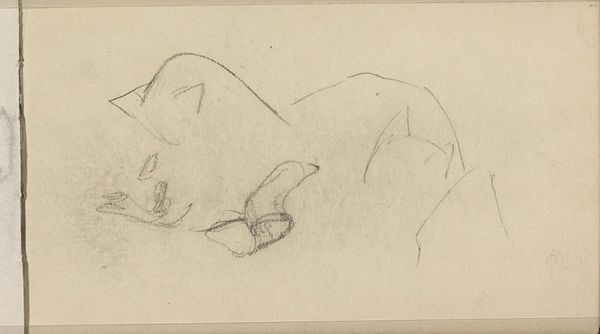

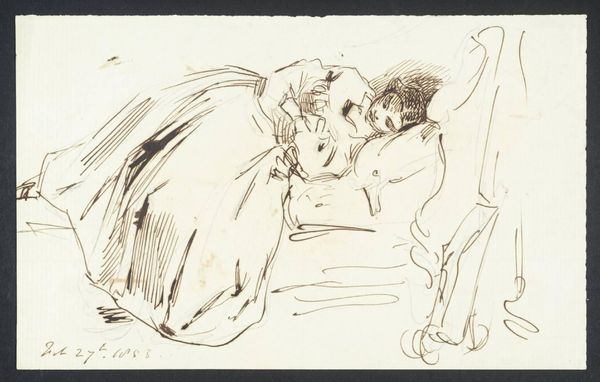

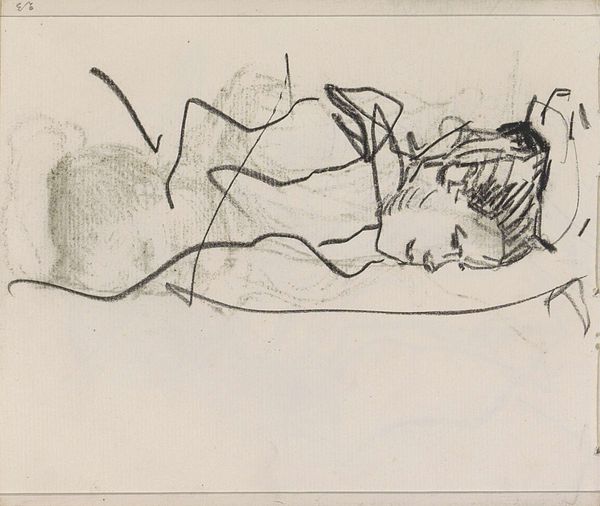

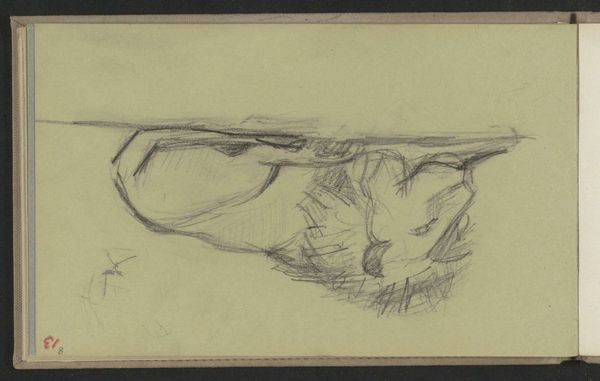

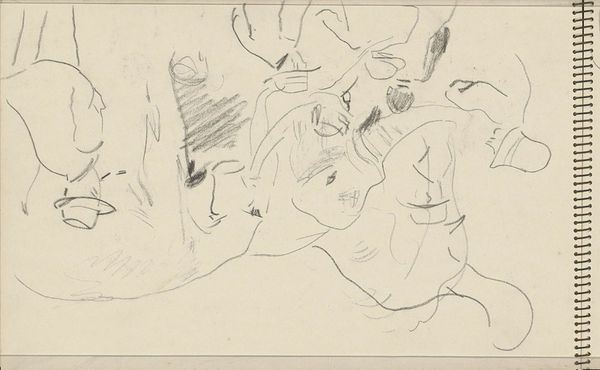

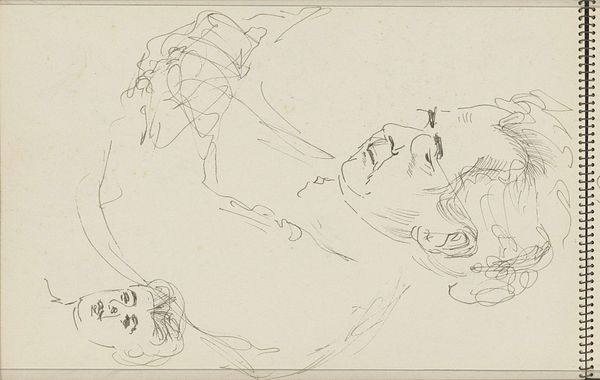

Curator: Isaac Israels' pencil drawing, "Twee vrouwenhoofden," which roughly translates to "Two Women's Heads," done sometime between 1887 and 1934. It's here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: A whisper of charcoal, barely there... two ghostly visages emerging from the paper's grain. Melancholy, or perhaps just lost in thought. There's a definite raw beauty to it, the lines unfinished. Curator: Raw is a good word for it. It feels so immediate. Looking closely, I get the sense Israels was trying to capture a fleeting moment, a particular mood or impression. It reminds me of Degas' quick studies of dancers. What really interests me are the possible connections of those working class female models. Editor: Absolutely. It is all about class, isn’t it? You can practically feel the pressure of the pencil on paper, documenting these faces... probably piecework, like those women performing their own labor, visible or not. The cheapness of pencil against costly canvas speaks volumes about access to materials. The sketch is an art object but also a record of that unequal transaction. Curator: That's insightful. I'm always drawn to that sketchy quality too. It has an honesty that a highly polished piece often lacks. It invites me to imagine, to co-create with the artist, almost like glimpsing the initial spark of an idea. And given Israels's focus on figures in motion, perhaps this sketch represents an exercise to practice gesture or build a record for his memories. Editor: Yes! The ephemerality is critical here. Not just the visible work, but also, the many revisions, now unseen. Also the kind of knowledge that does not necessarily translate into technical skill, but to what purpose, which commission. We are looking at a set of social and material relations there. I always wonder if the two subjects were looking in a mirror, perhaps sharing each other's material circumstances at the time of sketching. Curator: I'm left pondering about the women depicted here and how this fleeting encounter captures some unspoken essence of their being, filtered through the artist's perception. I am always attracted to Israels' portraits and depictions of common workers and regular, real subjects. Editor: Right. What began as what feels like the artist's solitary pursuit transforms into a collective memory through art. Now, it invites our reflections on not only art history but the silent labor embedded within.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.