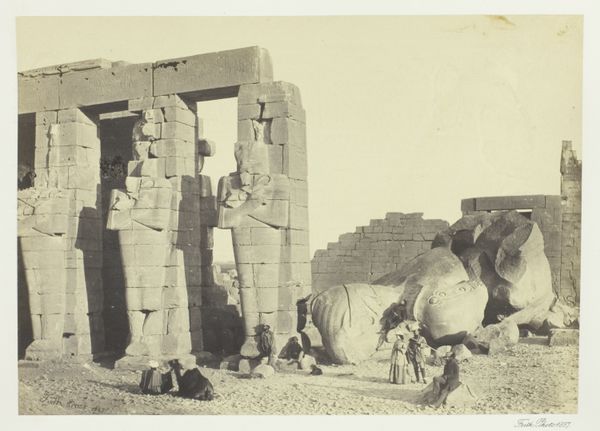

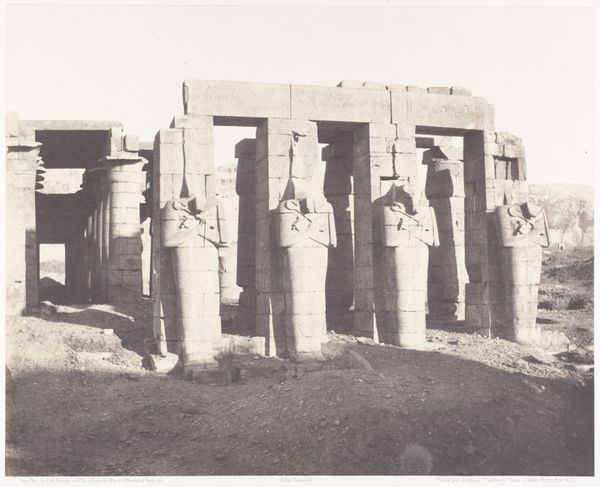

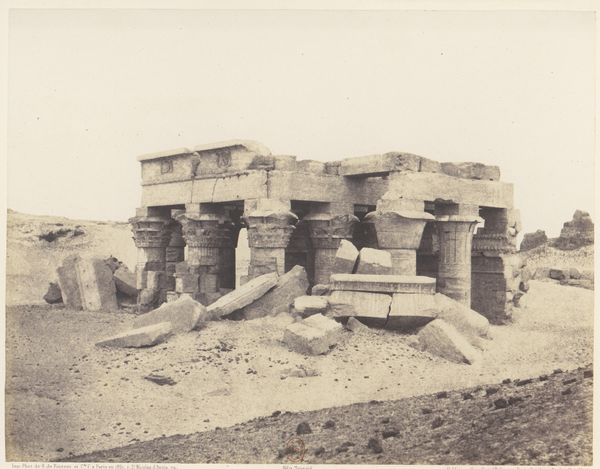

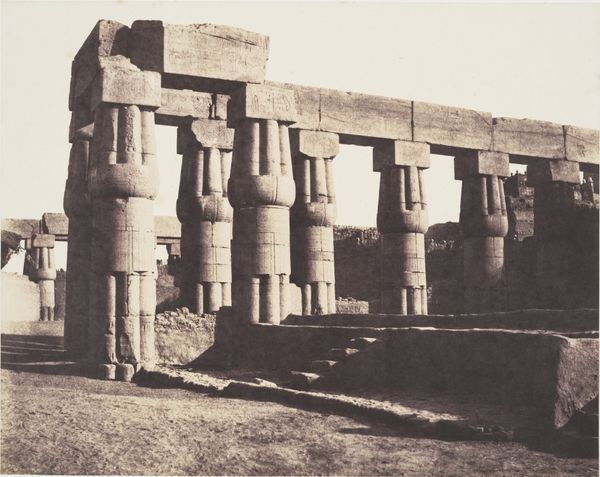

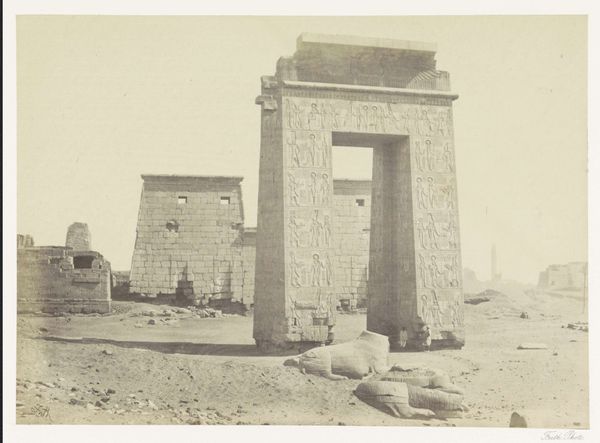

Osiride Pillars and Great Fallen Colossus c. 1857 - 1862

0:00

0:00

silver, print, photography

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

agricultural

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

realism

Dimensions: 14.3 × 22.7 cm (image); 31.6 × 43.4 cm (paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

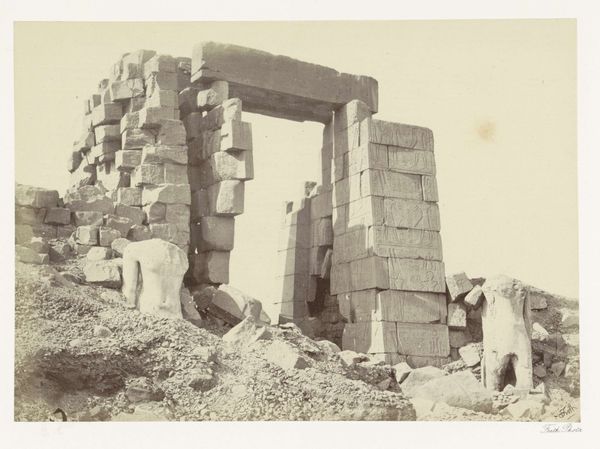

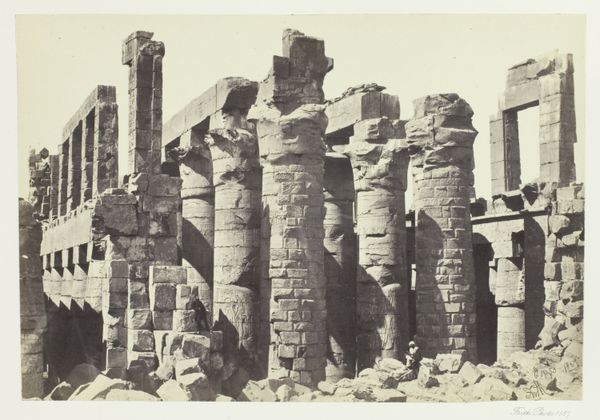

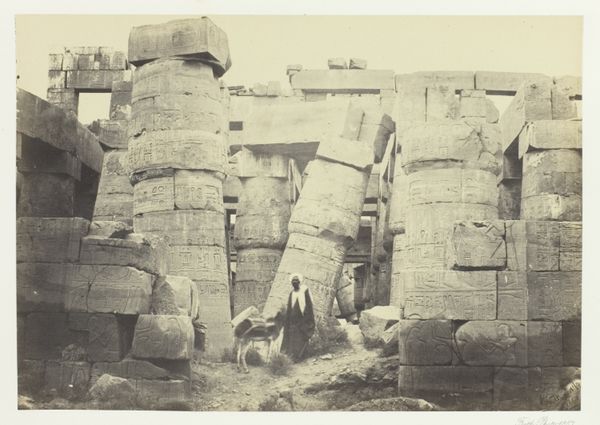

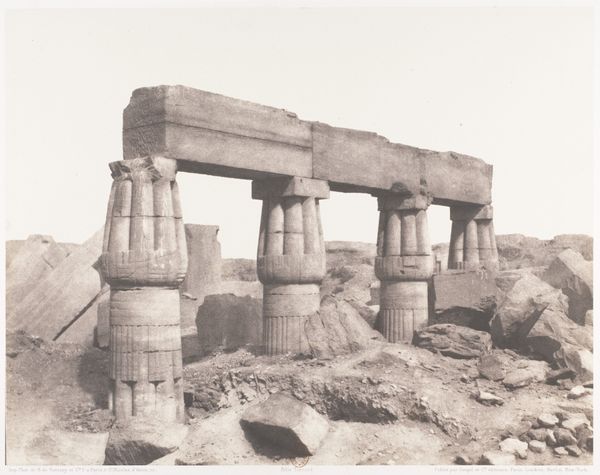

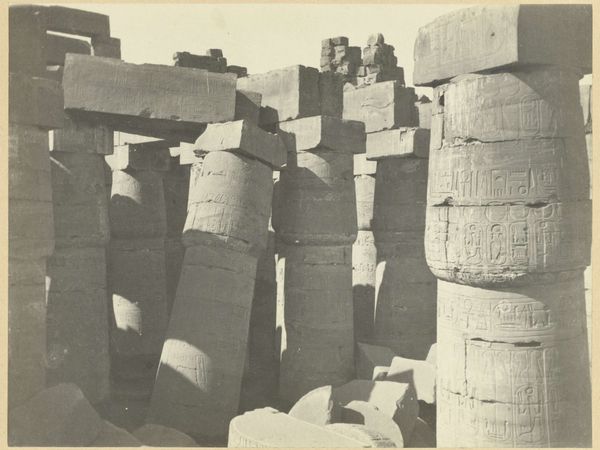

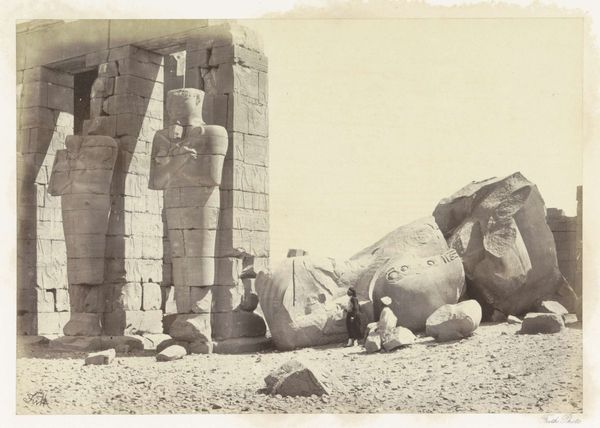

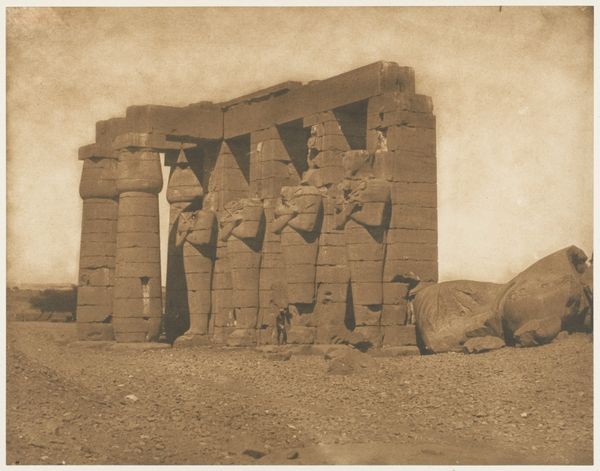

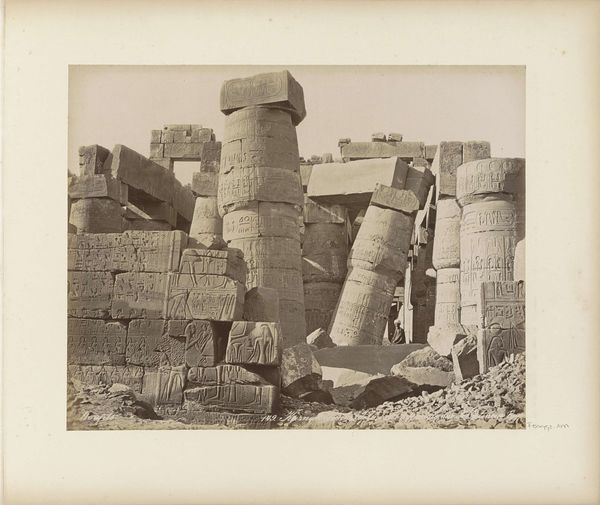

Curator: Before us, we have Francis Frith's photographic print, titled "Osiride Pillars and Great Fallen Colossus," likely taken between 1857 and 1862. It is currently held at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s…breathtakingly desolate. The scale is what strikes me first. The sheer mass of these fallen forms speaks volumes about time and decay. You can almost feel the weight of history bearing down. Curator: Absolutely. Frith's choice to photograph these ruins during this period speaks to the West's growing fascination with and, arguably, appropriation of ancient Egyptian history. Photography became a tool for documentation, and even exploitation, by making these distant places accessible to a European audience. Editor: I’m immediately drawn to the materiality, or rather, the *im*materiality implied. These are massive stone structures, monuments crafted by human labor over centuries. Now reduced to fragments…what a statement on human endeavor. The making and unmaking, really. Curator: Precisely. These images served not just as records, but as powerful symbols within a broader narrative of Western dominance and control, subtly reinforcing a hierarchy. Editor: What about the workers? See those figures in the photograph near the broken colossus. Their presence emphasizes not only scale, but also perhaps hints at the colonial project and the labour involved in these expeditions. It's not just ruins, but ruins observed through a particular social lens. The silver print medium gives a rich tonal scale, highlighting texture. Curator: Interesting observation. The aesthetic value of Frith's image helped shape the popular perception of Egypt at the time. Did these grand structures symbolize ancient glory, or perhaps were they warnings about the impermanence of civilizations and empires? It depends on who you ask. Editor: And who gets to do the asking, right? Even Frith’s method becomes material—silver printing, mass reproduction...turning monuments into commodities, into easily-consumed representations. How was the raw material for his photography extracted and who was providing it? A picture tells a thousand words, but so too, does the process. Curator: Indeed. It forces us to consider how photographs like this reinforced, or even challenged, existing social and political frameworks within both the Egyptian landscape, but moreover, how European powers projected influence. Editor: A poignant, material echo of a civilization and a lens that transforms stones into an artifact that both is, and isn’t, a window into a forgotten age. Curator: Very well said. The layers of historical narrative embedded within Frith’s print continue to raise critical questions, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.