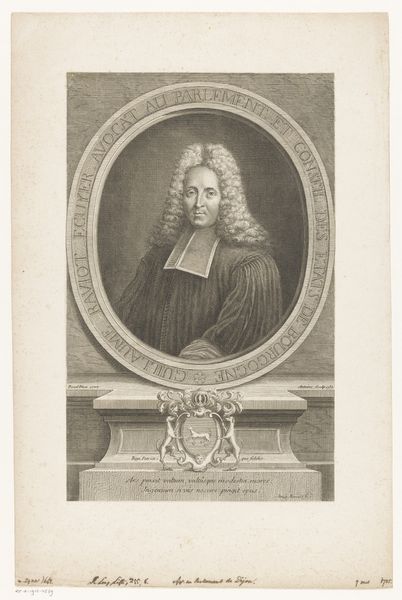

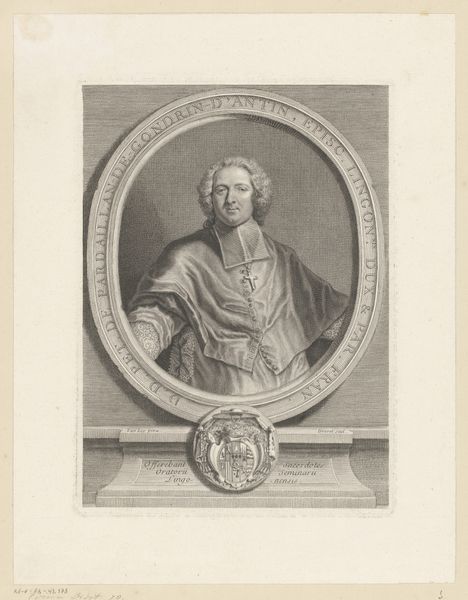

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 359 mm, width 249 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Today we're looking at Nicolas de Larmessin’s print, "Portret van Philippe Vleughels," created in 1732, an engraving after what I assume was a painted portrait. What’s your first impression? Editor: Well, beyond the old-world formality, it’s kind of… sweet? He looks approachable, not like your typical stern, be-wigged nobleman. The lines seem delicate. Curator: The engraving process itself is key to understanding that impression. Larmessin would have meticulously cut into a copper plate, transferring the original image through a complex system of labor, craft, and reproducibility. This wasn't about unique expression; it was about dissemination, about solidifying Vleughels' position in the art world. Editor: You know, it reminds me a bit of old money vibes. Everything is just slightly understated. Look at the draped fabric - luxurious, sure, but rendered in these soft, almost muted tones. And that oval frame is so classic; the text around him has aged to perfection with no more than a few nicks in it, beautiful and full of history. It makes me think, "What would it be like to step back and look at these historical images being created in their time?". Curator: Precisely. The social context here matters immensely. Vleughels was a painter who became director of the Académie de France in Rome, quite an achievement. The print then functions as both a record of his likeness and a form of cultural capital, connecting him to the academic establishment and broader artistic patronage networks. And with an engraver of Larmessin's reputation, it meant even wider viewership of the artwork itself than may have ever occurred by painting it and hoping that other important people saw it to then want more painted artworks by the artist depicted here. Editor: Right, a public declaration. There’s an interesting tension though – between the accessibility of the print and the elitism it subtly reinforces. It’s a Baroque portrait made accessible via mass printmaking for a greater range of audience viewers to consider than previously before in earlier generations, something to reflect on there, too. Curator: I agree. Considering the mode of its creation – engraving on metal plate – and its intended function as publicity is also relevant; what happens to the value assigned by an art marketplace when more people can own a piece for less expenditure is yet something different that should not be forgotten. Editor: The artist depicted and the engraver's own contributions become inseparable parts of this visual moment as time has marched onwards too. Both creative actions in that sense contributed, if not equally, to how this art will be forever interpreted now through different modern sensibilities than just Baroque. It is a collaboration after all of art and human intention made concrete.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.