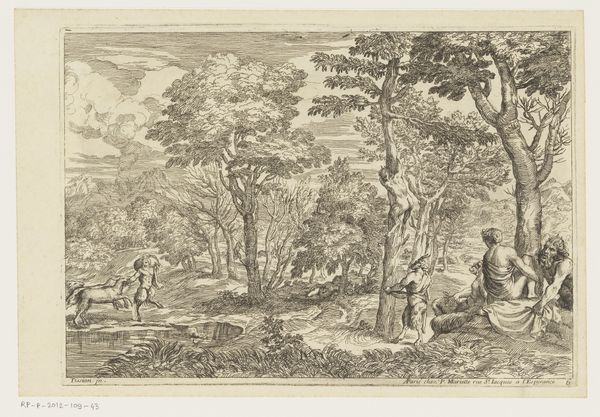

drawing, print, etching, intaglio, engraving

#

pen and ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

intaglio

#

landscape

#

etching

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 15.2 × 27 cm (6 × 10 5/8 in.); trimmed within platemark

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This is "River Landscape with Tobias and the Angel" made around 1648 by John Galioth Nardois, created with etching, engraving, and other intaglio methods. It's such a detailed print; I am immediately drawn into the landscape. What do you see in this piece that stands out to you? Curator: Well, beyond the immediate pastoral scene, it's vital to recognize that even ostensibly religious scenes reflect and refract the complex societal values of their time. Nardois presents a landscape that feels almost like a stage. Consider the roles—Tobias, the dutiful son, and the angel, a figure of divine guidance. What narrative is implicitly reinforced through this visual hierarchy? Editor: That's an interesting point about the hierarchy. I hadn’t considered the staging of the landscape as part of that message. Curator: Exactly! Look closer—the meticulous details applied with pen and ink reflect a particular aesthetic preference, of course, but more subtly, also the patronage of an elite audience. Ask yourself: whose stories get told, and whose visions get circulated through art? Editor: So, the artistry isn't just technical skill, but also a carrier of social ideas and class distinctions. Curator: Precisely. Moreover, exploring Baroque art, it's worthwhile investigating the prevailing historical, philosophical, and social currents of the era. Are there other visual components, beyond the relationship of Tobias and the Angel, that suggest specific philosophical considerations that mirror historical inequities, or power imbalances? Editor: Now that I look again, the distant landscape seems almost inaccessible, dominated by the immediate foreground, which could suggest something about limited horizons for the figures within the scene. It makes me consider what we’re not seeing, too. Curator: Yes, precisely that. Recognizing those artistic exclusions offers us more robust and thorough historical comprehension. Editor: Thanks! It changes the way I’ll approach other landscape pieces from the period. Curator: Indeed. Remember that understanding context can liberate art history, allowing for richer conversations regarding who is represented, how they are represented, and, critically, what voices are deliberately absent from representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.