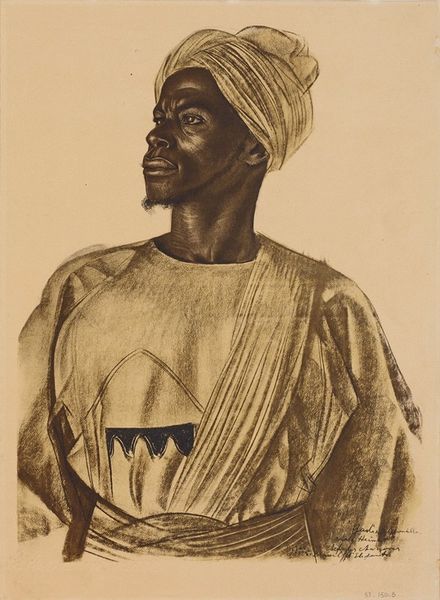

Copyright: Public domain

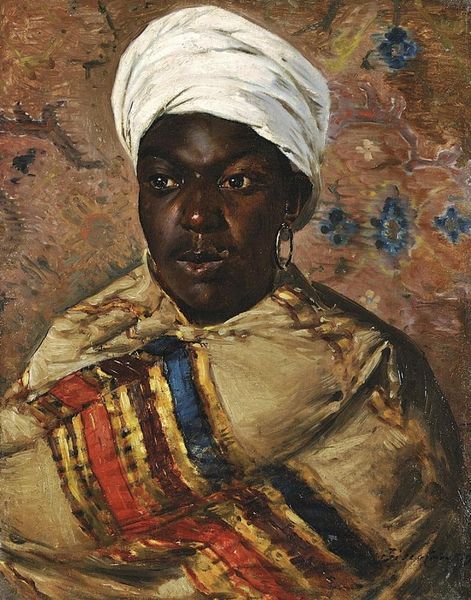

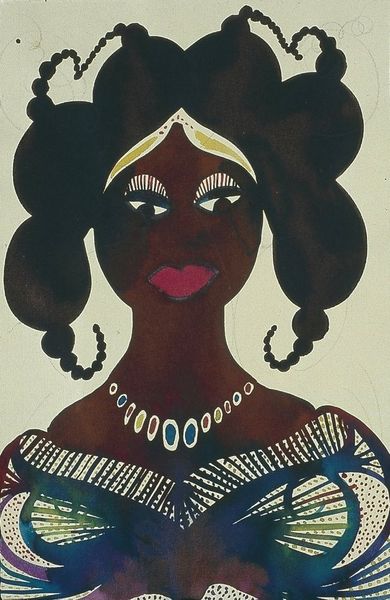

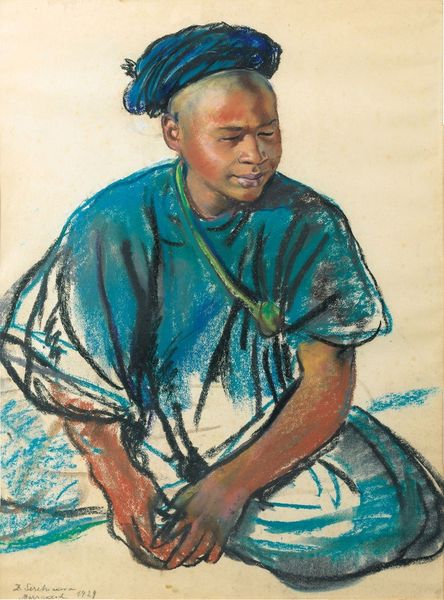

Editor: Here we have "Massaida," a pastel drawing from 1912 by Théophile Alexandre Steinlen. There's something striking about the sitter's direct gaze and the vibrant colours... How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see a portrait deeply embedded within the complexities of early 20th-century Europe, grappling with colonialism and exoticism. Steinlen, known for his social realism, here engages with the prevailing fascination with African cultures, but it's crucial to ask: From whose perspective? How does the Western gaze shape the representation of Massaida? Editor: That’s interesting! I hadn't really thought about the implications of that gaze. What specifically in the artwork leads you to this reading? Curator: Consider the title itself, likely referencing the Maasai people. Does it genuinely represent an individual, or does it flatten her into a symbol of an entire continent? Look at the composition, the rich colours. Are they celebrating her individuality, or are they performing a kind of visual "othering" common in that era? We need to be aware of art history but interrogate the narrative. What is being celebrated, and at whose expense? Editor: So, you’re suggesting the portrait, while beautiful, potentially perpetuates stereotypical views. Does Steinlen's other work give us any clues to his intentions? Curator: Precisely. And yes, looking at his broader body of work, including his illustrations for social causes, might offer a more nuanced understanding, but it does not excuse the problems of representation present within this single portrait. Are her own views, her own lived experiences included? Almost certainly not. And it's vital for us to acknowledge that absence. Editor: That’s given me a lot to think about. I guess I was initially drawn to the aesthetics, but I see now there’s a far more complex conversation happening here about representation and power. Curator: Exactly. This isn't just about aesthetics; it’s about engaging critically with the historical and social context that shaped this image, and by understanding whose voices are present - and importantly, absent - we are better equipped to comprehend our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.