print, etching

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 79 mm, width 73 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

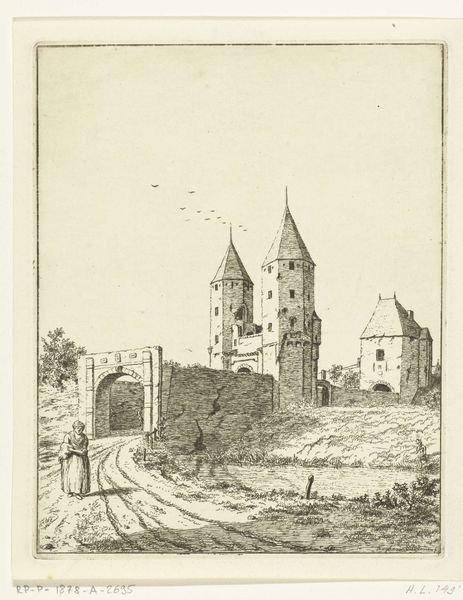

Curator: Today, we’re looking at Israel Silvestre’s 1656 etching, “View of a City Gate of Clermont,” currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. It captures a moment in the life of a bustling urban center. Editor: It strikes me as so fragile, almost a sketch caught mid-thought. The lines are so delicate, and yet they suggest such weighty structures – stone and social hierarchies both. Curator: Absolutely. The technique itself – etching – is crucial. Silvestre used a metal plate, covered with a waxy ground. He then drew through this ground, exposing the metal, and submerged it in acid. This process of controlled corrosion allowed for incredibly fine, detailed lines. Editor: The crumbling gate looms so large, it suggests decay but also the power of historical precedence, I see echoes of medieval power structures and the inequalities in early urban planning. How does Silvestre handle the narrative around urbanization during this time, do you think? Curator: Well, this print, like many of Silvestre's works, served a specific function within a larger economy of image production. These prints would have been widely circulated and sold to people invested in maintaining their positions in the old aristocracy. Consider the materials – the metal plate itself, likely sourced through trade networks, the acid, the paper. Every stage involved labor and economic exchange, creating an object intended for relatively wide distribution to people seeking evidence of past glories. Editor: The figures almost feel like stage props – are they more representative or playing into an allegorical representation of societal rank? The figures at the front, perhaps members of the working classes, observe as someone of more 'importance' appears in transit on horseback? Is this a study of a very fixed system, perhaps critiquing through capturing such obvious inequity? Curator: The relationship between technique and subject matter opens a space for just such an argument to be had around the purpose and implications of Silvestre's art; in choosing such fragile materiality he allows it to stand as a document of something historically monumental that would and could never truly return. Editor: I am so caught up on how fleeting it feels. The delicate lines, the crumbling architecture… it is as though Silvestre is intentionally suggesting that nothing will truly stand the test of time and, furthermore, there is power in such awareness. Curator: His work prompts us to consider not just what is represented, but how it came to be represented, by whom, and for what purpose. It makes us rethink not just this scene from 1656, but about everything we know about what survives for the study of history in material culture. Editor: Yes, seeing art in context encourages critical evaluation of historical periods. So much to unpack in this tiny scene!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.