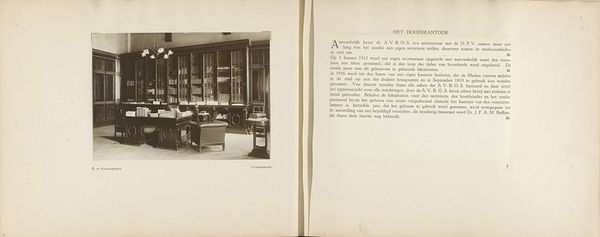

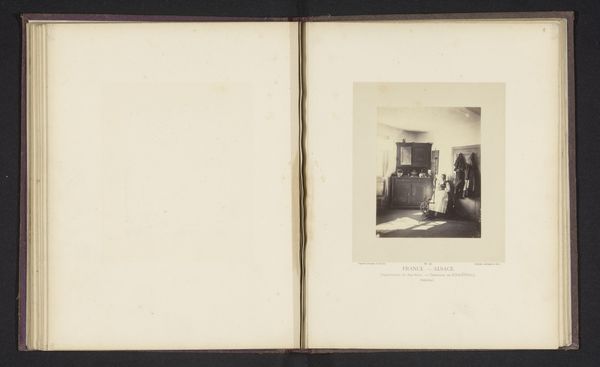

Pagina 4 en 5 van fotoboek van de Algemeene Vereeniging van Rubberplanters ter Oostkust van Sumatra (A.V.R.O.S.) c. 1924 - 1925

0:00

0:00

jwmeyster

Rijksmuseum

print, photography, albumen-print

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

photography

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 310 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

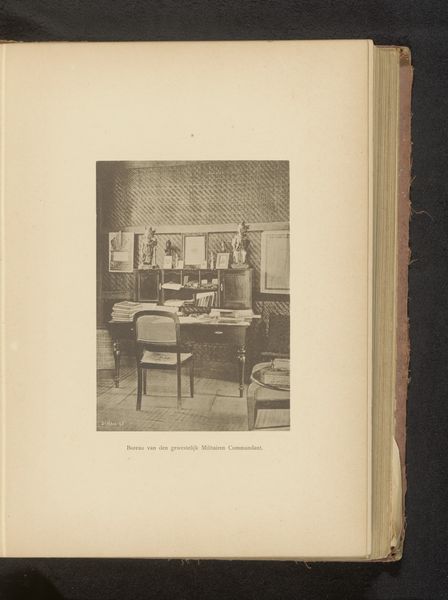

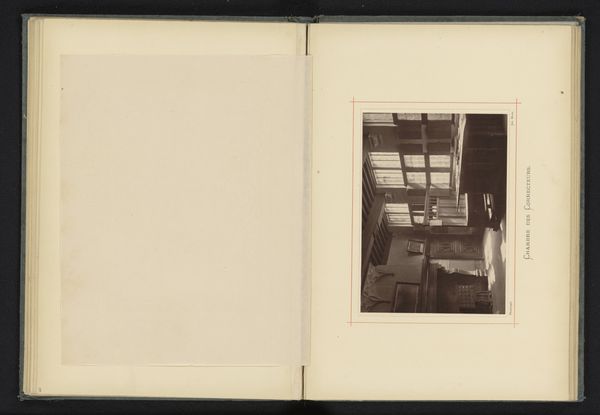

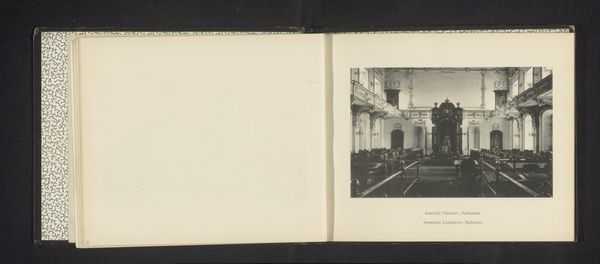

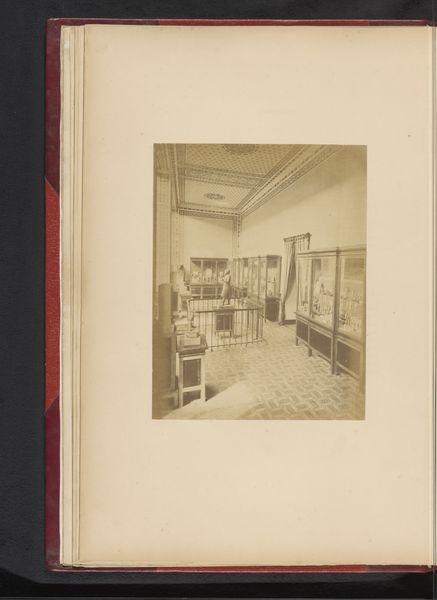

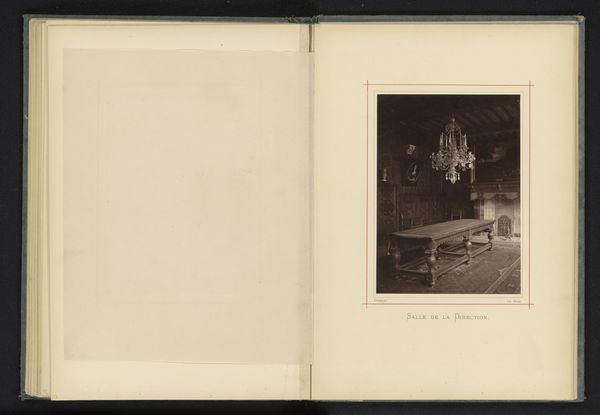

Curator: These are pages 4 and 5 from a photo book from the General Association of Rubber Planters on the East Coast of Sumatra, or A.V.R.O.S., dating to around 1924 or 1925. It’s currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is the heavy stillness, the quiet order of the space. It's almost melancholic, and certainly sterile in its representation of, what seems to be, a conference room. It highlights for me a strange disconnect to the brutal labor of the fields that gave rise to the need for such a formal, stately place. Curator: That is an astute observation! Indeed, there’s a profound visual symbolism here, perhaps unintended, between the staged elegance of the interior setting and the complex, often exploitative reality of rubber production during that colonial period. The arrangement evokes a particular kind of power. Editor: Exactly. These albumen prints – a photographic process reliant on egg whites for binding the photographic chemicals to paper – present us with a fascinating material contradiction. Delicacy imposed upon images tied to something harsh, far removed from clean, efficient meetings in chambers such as these. This feels more than an image. Curator: I agree. The chairs, precisely spaced, act as recurring visual cues. One thinks not just of colonial authority but also the cultural memory embedded in images of interiors. The composition even implies the exclusion and otherness projected onto the land’s workers themselves who are visibly excluded from the 'chambers'. The albumen is acting as the thinnest facade on which a vast landscape of social conflict plays. Editor: The very making of this photo book, printed ink on paper, reveals an elaborate network of extraction. Sumatran rubber flows West, becoming bound by processes intended to give order, give justification. These pictures naturalize inequality through mundane compositions and their placement in photo albums meant to circulate amongst European society. Curator: Well said. It is compelling to consider these seemingly simple images within the frame of that greater colonial project, where symbols of power are made tangible through architecture, photography, and publication. The images aren’t simply records. Editor: Precisely. To me, examining the means by which we encounter images from this era illuminates, like this space, so much more than initially meets the eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.