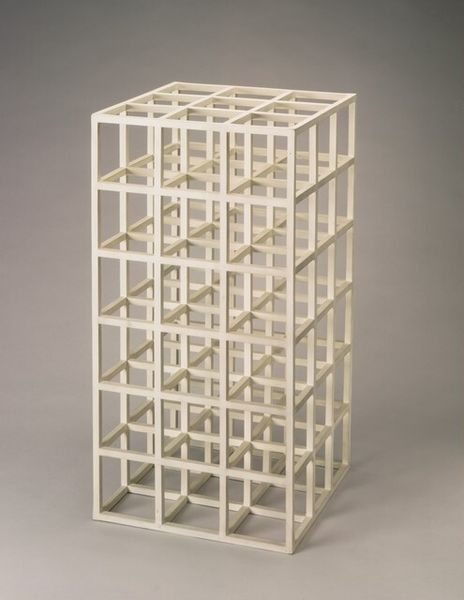

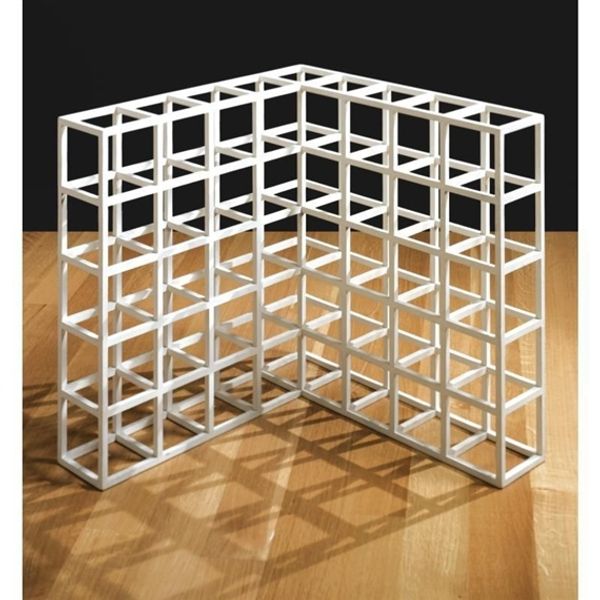

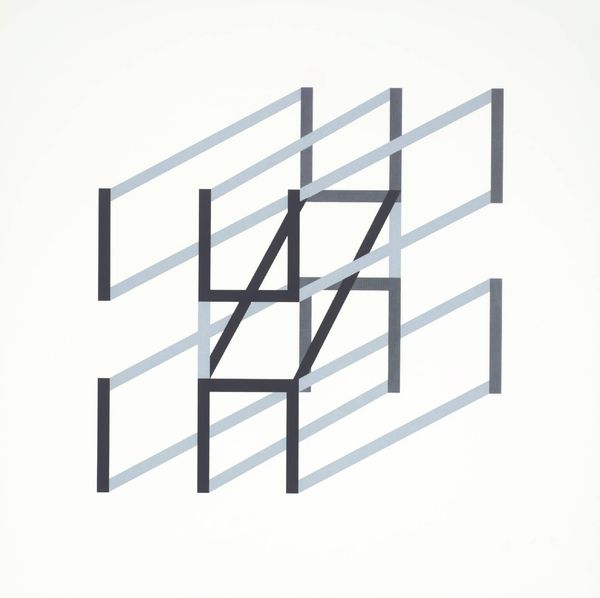

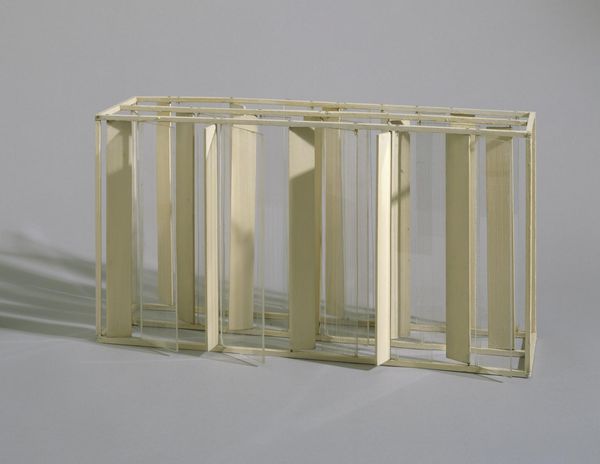

sculpture

#

render graph

#

architectural and planning render

#

3d model

#

3d rendering

#

architectural modelling rendering

#

conceptual-art

#

minimalism

#

plastic material rendering

#

furniture

#

virtual 3d design

#

form

#

geometric

#

sculpture

#

architectural render

#

abstraction

#

3d modeling

#

architecture render

Copyright: Sol LeWitt,Fair Use

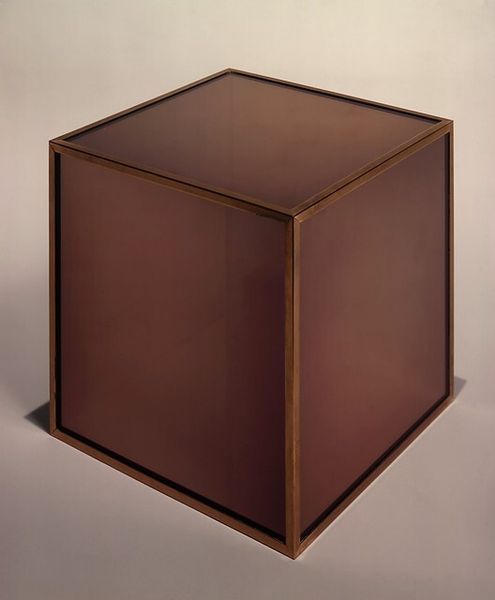

Editor: So, here we have Sol LeWitt’s "8 Part Cube" from 1975, a sculpture… well, more of a three-dimensional diagram, really. It’s interesting how the simplicity of the white cube is complicated by the interior structure. It seems to both reveal and conceal its own construction. What ideas do you think LeWitt was trying to explore? Curator: LeWitt was deeply engaged in challenging conventional ideas about what constitutes art. During the late 60s and 70s, the art world was questioning the role of the artist, the object, and even the gallery itself. Conceptual Art and Minimalism arose, in part, as responses to the perceived commodification of art, pushing back against abstract expressionism's emphasis on the artist's individual touch. This piece embodies that. It prioritizes the underlying concept, the idea of the cube, rather than a specific emotional or aesthetic experience. The cube is broken down, examined, almost diagrammed. Don't you agree that that structure questions institutional frameworks? Editor: I can definitely see that. It's like he's dissecting the very idea of a cube, removing any sense of monumentality. In doing so, he seems to question art's traditional role as something precious and unique, something to be passively admired. But why the focus on geometry? Curator: Geometry provided a vocabulary free from personal expression, a rational system accessible to all. This democratic approach aligns with the larger counter-cultural movements happening at the time, protesting against established hierarchies in the art world. LeWitt, in his writings, advocated for the artist as a kind of architect or engineer, someone who conceives an idea, which could then be fabricated by others. The concept is the art, and it should be openly available for anyone to interpret and realize. Doesn't that approach break down preconceived notions about the artist and how their work is made and received? Editor: Absolutely. I never thought about Minimalism as a counter-cultural statement, but it makes so much sense in that context. I used to see it as purely formal, about lines and shapes. Curator: It’s often been seen that way, particularly because museums themselves tend to isolate art from its original context. The institutional framework really shapes our perceptions. Seeing how these shapes come to life against social disruption provides additional depth. Editor: It really changes how I see LeWitt's cube, too. Thinking about the political context of the late '60s and early '70s, suddenly its rigid geometry feels charged with meaning. Curator: Precisely. Art and social history can work together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.