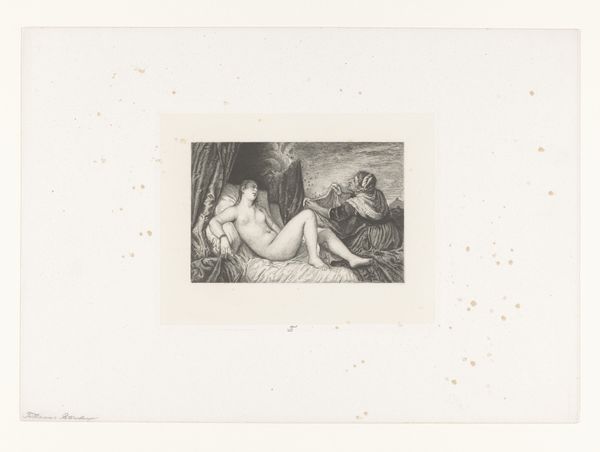

Dimensions: height 183 mm, width 253 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

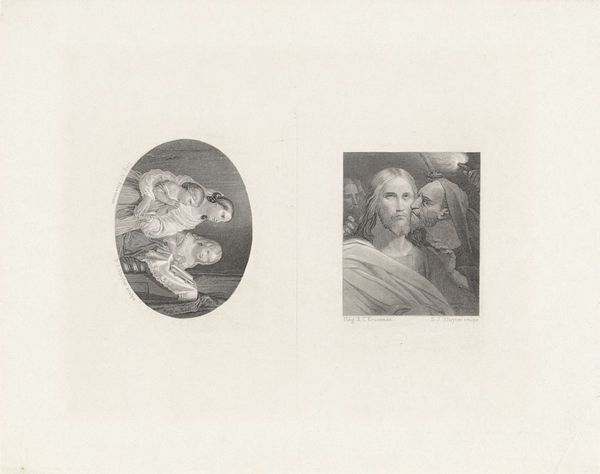

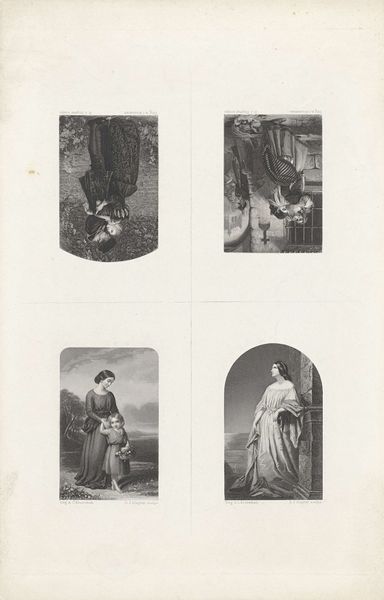

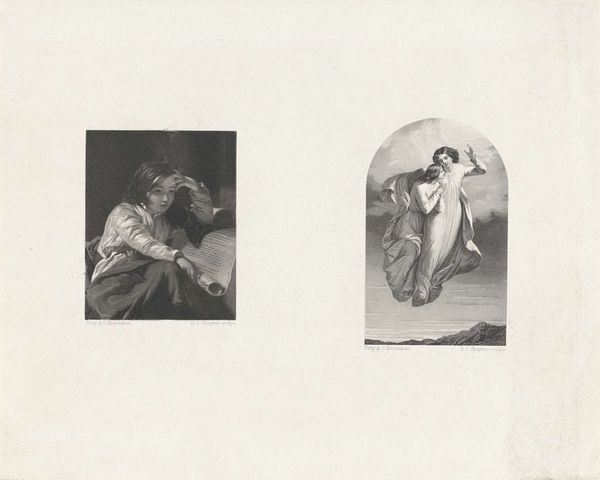

Curator: This engraving from between 1842 and 1873 is entitled "Young Woman on her Doorstep - Christ and John," attributed to Dirk Jurriaan Sluyter, now held at the Rijksmuseum. It's comprised of two separate panels on one sheet. Editor: It's striking how these small scenes invite contemplation, despite the difference in settings: an exterior scene filled with flourishing flora alongside an enclosed moment of interiority and spiritual connection. I’m struck by how both appear heavy with feeling, even solemn. Curator: I find the duality intriguing, both aesthetically and within the context of 19th-century artistic production and dissemination. The print medium democratized art; engravings allowed images to be reproduced widely, reaching broader audiences. This potentially creates interesting consumption habits between the two works. Editor: True. The image of the woman alone almost seems plucked from everyday life. Yet the engraving technique, demanding precise labor and skill, elevates it. Do you feel the two relate in any way? Perhaps two depictions of longing, just placed on differing plains? Curator: I appreciate the read as mirroring moments in time, with one existing on the earthly, and another elevated to a more divine stance. Placing these scenes together creates an odd narrative, because in isolation I wouldn’t expect a historical painting or religious iconography adjacent a portrait. But, of course, the image of Christ embraces the Romantic-era trend of emotional rendering, drawing from history painting traditions and giving it wide appeal to various consumers and belief systems. Editor: Indeed, viewing practices shaped what was valuable; what something stood for. And what someone was willing to consume or place in their domestic life. I keep returning to the composition - I believe Sluyter forces a conversation between piety and the quiet dignity of women's everyday lives through clever placement. Both prints create a sense of intimate interaction for the consumer. Curator: So, by reflecting on the societal contexts that surround even the making of this art, we reveal the intricate web of forces— labor, technology, belief, desire, and expectation—that shape how we come to view this composite image today. Editor: Absolutely. What once might have seemed just decorative, produced for easy domestic consumption, holds much deeper reflections about culture, religion, gender, and print culture, viewed in this manner. It certainly encourages revisiting accepted interpretations of this era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.