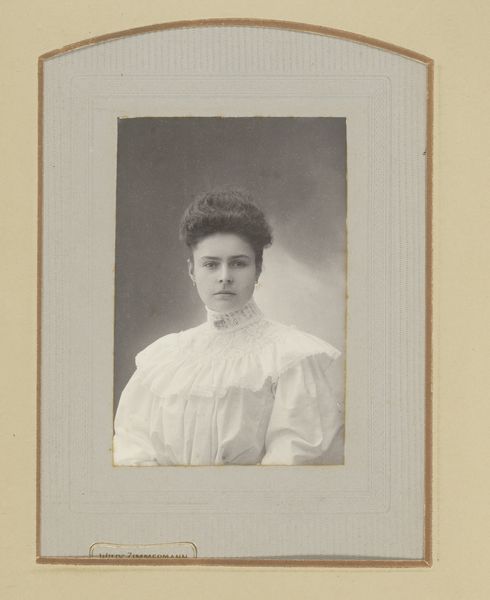

Portret van mevrouw Marie Jeannette de Lange (1865-1923), later echtgenote van Jan Bouman c. 1885

0:00

0:00

kameke

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 95 mm, height 260 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a captivating albumen print, a portrait of Marie Jeannette de Lange, circa 1885, now residing at the Rijksmuseum. She would later become the wife of Jan Bouman. What strikes you first about this piece? Editor: It's ghostly, almost ethereally pale. The limited tonal range lends a feeling of timelessness but also, frankly, a sense of the constraints of early photographic technology. The frame also reminds me of how precious this form of record-keeping was for families at the time. Curator: Absolutely. The albumen print process, where egg whites were used to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper, was quite labor-intensive. But look at the composition—her gaze is directed off to the side, creating a sense of thoughtful contemplation, pulling us into her interiority. In the context of the 1880s, what narratives about women does this evoke? Editor: Well, in that era, photography was becoming a powerful tool for constructing and reinforcing bourgeois identities. The subject’s dress is simple, but her carefully styled hair suggests middle-class respectability. We need to think about who had access to this technology, who could afford to sit for portraits like these. What's being materially represented but, moreover, what stories of class are told or excluded? Curator: Precisely. While appearing as a simple portrait, the image underscores issues of representation and power, class and gender norms—Marie's position is passively active, poised at a moment between availability and constraint, a reflection, perhaps, of women's limited social agency in that period. Editor: It makes you consider the material reality of photographic production itself. How were these portraits consumed? Were they displayed prominently or kept privately? I wonder, too, about the photographer – were they aware of the kind of status construction this represented? Curator: Those are crucial questions to consider. And through her gaze, we become active participants in this discourse, questioning the societal conditions that shaped her image and existence. It gives space to her representation to be much more. Editor: The tactile nature of the print, the almost sepia-toned hues speak volumes about the labour and material involved, which contrasts rather heavily to how quick and effortless making such image might appear now. This image serves as a quiet statement to such modern advances in both image production and, indeed, perception. Curator: Indeed. It’s a beautiful example of how historical photography can spark reflections on materiality, labor and wider themes of identity. Editor: Definitely makes me more aware about how material and image-making shapes our stories even to this day!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.