drawing, intaglio, paper, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

book

#

intaglio

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

charcoal art

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

pen

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

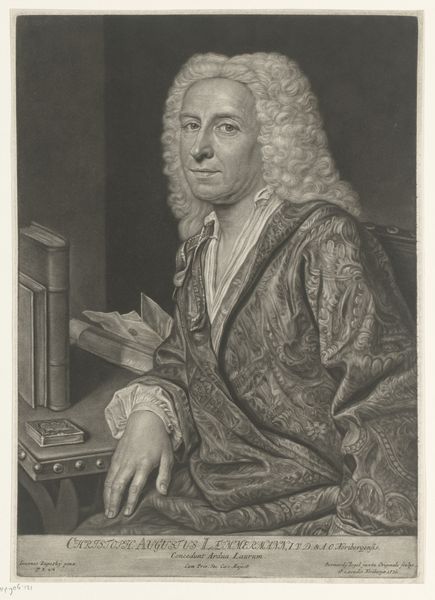

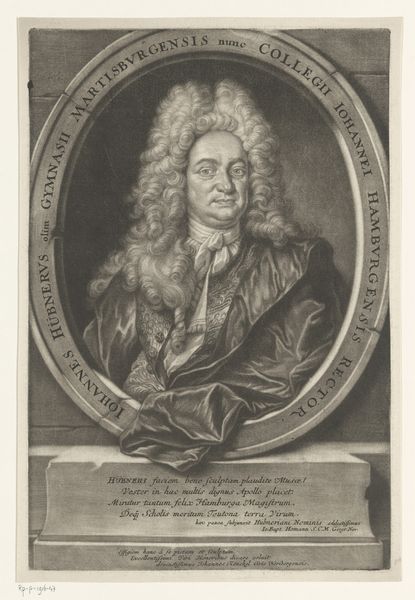

Dimensions: height 350 mm, width 252 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Gottfried Thomasius, created between 1727 and 1746 by Valentin Daniel Preissler. It's rendered using a combination of pen, charcoal, and intaglio on paper. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the formality and staged nature of the piece. The severe pose, combined with the almost theatrical lighting, really places Thomasius within a very specific social and intellectual framework. Curator: Exactly. Let’s consider Preissler's method. The labor invested in achieving such fine details with pen, charcoal and intaglio—the way he carefully constructed textures on the paper— speaks to the importance of skilled craftsmanship within the Baroque era. There’s an interplay of handmade versus reproductive quality, since intaglio allows for printmaking. How would this impact his reach to his audience? Editor: Absolutely. And if we look closer, who *is* Thomasius and what statement is being made here? The prominent book he holds speaks to the growing culture of scholarship and print media’s role in disseminating knowledge during the period. The background reinforces this identity; note the implied access to vast libraries. Thomasius's elevated status can be contextualized with broader access to education for bourgeois citizens in the Early Modern era. Curator: Preissler isn’t merely depicting him. Consider the precise pressure of the pen strokes to render the subject's clothing: the expensive fabric, buttons, elaborate cuffs… Each aspect deliberately indicates social standing. He's manufacturing a very particular image of a prominent intellectual for public consumption, showing that portraits, engravings or any form of visual culture can produce hierarchical roles. Editor: That brings up an interesting point about the artist's role, too. Who commissioned this piece and why? Considering that printed intaglio engravings could be circulated broadly, there’s clearly an intended audience and message embedded in this representation of learned status and access to knowledge. This creates a cultural authority—we see these repeated even in modern forms of self-presentation. Curator: Ultimately, this portrait serves as a record of production practices prevalent in the Baroque period, evidencing a keen interest in social stratification and material wealth within artistic representations. Editor: Agreed. Understanding that representation helps us deconstruct visual power dynamics that are, frankly, still circulating today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.