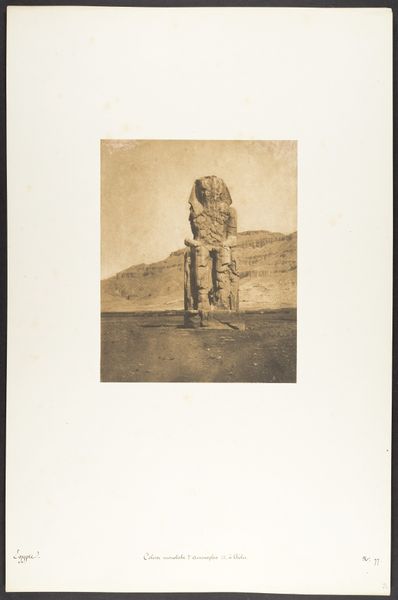

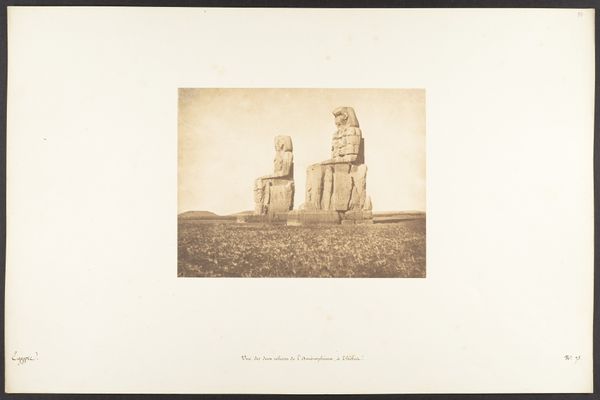

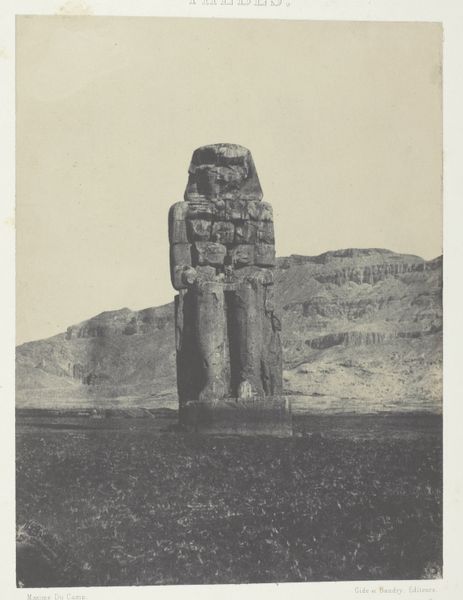

Colosse restauré d' Aménophis III, à Thèbes (Statue vocale ou Colosse de Memnon) 1849 - 1850

0:00

0:00

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: Image: 7 13/16 × 6 5/16 in. (19.8 × 16 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

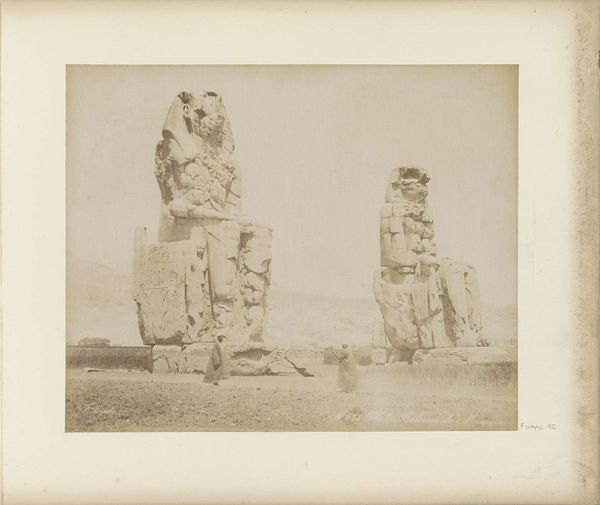

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, captured between 1849 and 1850, presents the Colossi of Memnon at Thebes. The photographer, Maxime Du Camp, immortalized these imposing sculptures of Amenophis III. Editor: The immediate impression is one of solemn grandeur, though scarred by time. The statue seems almost otherworldly against the landscape, and the sepia tones contribute to a feeling of immense age and loss. Curator: Indeed. Du Camp's photographs, commissioned by the French government, served to document Egypt’s monuments and reflect France's colonial ambitions during that era, seeking to possess knowledge of other cultures through photographic reproduction and study. This photograph participates in a broader history of Orientalism. Editor: So, it’s a depiction meant to inform, but also implicitly to control? The angle makes the sculpture dominate the landscape and that reinforces ideas of power and ancient, impenetrable knowledge. How was it originally intended to function for the Egyptians, though? Curator: The Colossi served as guardians of Amenhotep III's mortuary temple, a symbol of his divine power and connection to the gods. These served a powerful function, until their collapse, which created sounds interpreted as divine utterances. These became sonic sculptures for a while and contributed to ancient religious practices in the Theban necropolis. Editor: Interesting how their 'usefulness' evolved. Even in this ruined state they held sway over people's minds. It brings forth the question of how we understand cultural patrimony, then and now. And what did it mean for Du Camp and his French contemporaries to claim and represent these ruins? Curator: The photograph allows a controlled and, perhaps, decontextualized engagement. Its function shifts. What was once an important component of royal religious ritual gets transferred to the scientific study of antiquities. This tension underscores our ever-evolving relationship with the past, always framed by power structures. Editor: I see now a meditation on resilience, a witness to countless seasons. Thank you, for helping me to observe how power, ruin, and memory intersect in this seemingly straightforward landscape. Curator: And, for helping me understand the multiple roles it played between historical context, artistic appropriation, and contemporary significance. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.