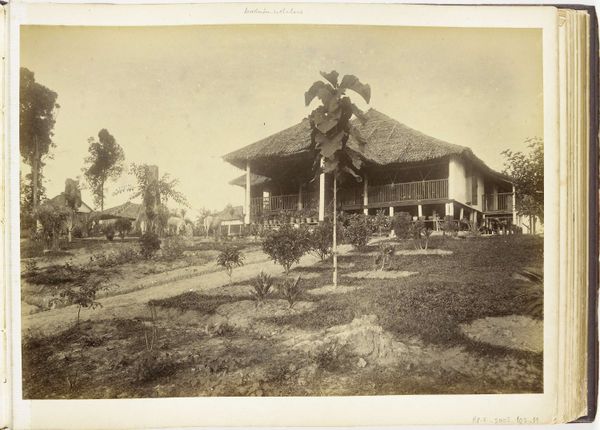

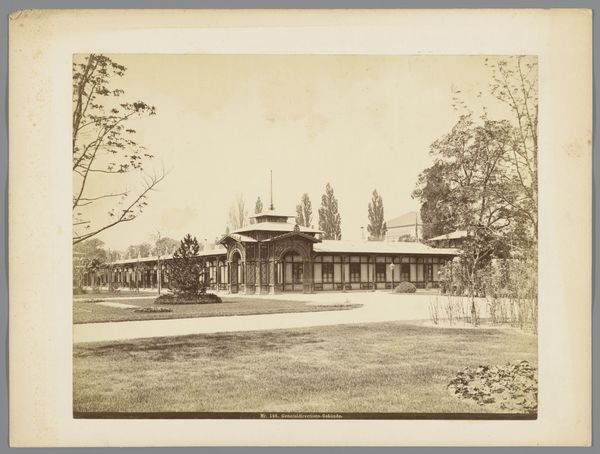

Moskee of Mesjid met minaret en bijgebouwen in Kota Baru, vermoedelijk op Sumatra 1891 - 1912

0:00

0:00

christiaanbenjaminnieuwenhuis

Rijksmuseum

photography, site-specific

#

landscape

#

photography

#

site-specific

#

19th century

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 289 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This photograph, taken between 1891 and 1912, presents a view of the Moskee of Mesjid with its minaret and outbuildings in Kota Baru, likely located in Sumatra. It's attributed to Christiaan Benjamin Nieuwenhuis. Editor: My first thought is how the light almost seems to cling to the textures, doesn’t it? You can practically feel the coarseness of the thatching and the smooth, almost rendered look of the minaret. The muted tones really emphasize those material differences. Curator: Yes, it's interesting how Nieuwenhuis captures this Islamic structure within the context of the Dutch colonial presence in the region. Photography like this played a crucial role in shaping perceptions of the 'East' back in Europe. This image functions, in some ways, as a tool for documenting and, perhaps, subtly asserting control. Editor: Absolutely. And when you think about the labor involved in constructing this mosque, the photograph sort of flattens it out, doesn’t it? All that intricate work in wood and plaster—the hands that built it—becomes just a visual detail. But considering the social context, this mosque becomes an amazing example of local craft production using indigenous resources in a colonized landscape. Curator: Exactly! The architecture merges local tradition with Islamic design principles, while the image itself participates in a colonial visual culture. It becomes this complex layering of cultures and power structures. Consider how photographs were often displayed in exhibitions and used in ethnographic studies to construct a particular narrative about colonized people. Editor: Right. It's easy to romanticize these historical photographs, to lose ourselves in the exoticism. But foregrounding materials—what things are made of and how that production impacts the cultural, political, and environmental—really does anchor the photograph in material reality. Curator: Thinking about the broader history, it's worth pondering the ethical responsibilities tied to the conservation and display of such imagery today, and how institutions like the Rijksmuseum, where this photograph resides, approach that challenge. Editor: Definitely. So much information about the original social conditions—of material exploitation, even—can be lost without a mindful unpacking of colonial images. The surface allure distracts from the complex production chains. Curator: This has really broadened my thinking. Editor: Mine too, these are always fascinating cross-examinations of image and historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.