drawing, paper, pencil, graphite

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

impressionism

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

graphite

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

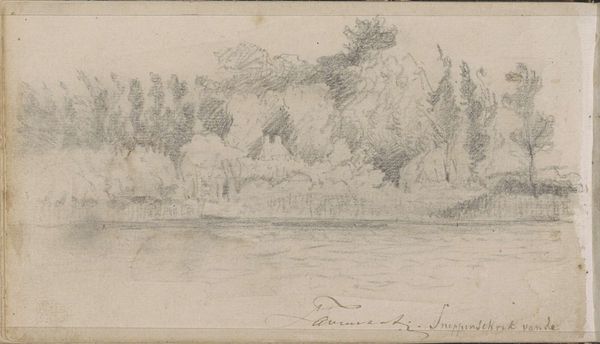

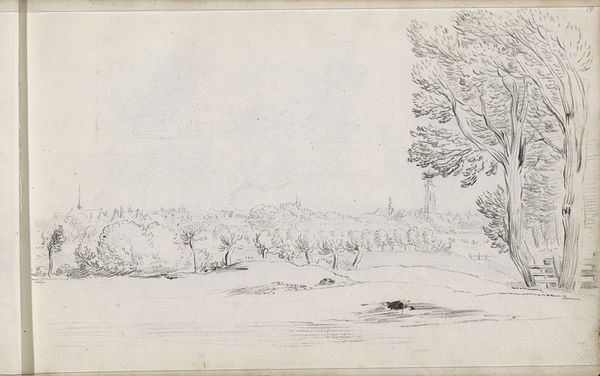

Curator: Immediately, I am drawn into the peaceful stillness of this landscape, a reverie captured in soft graphite. It almost feels like a whisper of a place, doesn’t it? Editor: Indeed. This is "Bergschenhoekse Polder" by Johannes Tavenraat, made between 1864 and 1868. The use of pencil and graphite on paper lends it a fleeting, almost ephemeral quality. Considering its place in the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch landscape tradition speaks volumes here. Curator: Fleeting is precisely the word. It's like catching a memory just before it fades. The solitary tree standing tall amid the low-lying land evokes a sense of resilience and quiet dignity. What do you think? Editor: I see something deeper. Polders are, by definition, reclaimed lands. Their existence speaks to the ceaseless labor of the Dutch people to reshape their environment. So this isn't just a peaceful landscape; it represents a complex relationship between humans and nature, the constant negotiation and manipulation of the land for survival. It raises critical questions about environmental sustainability, the anthropocene and its legacy. Curator: Ah, I hadn't considered that angle! You are so right; there is more at play than a simple bucolic scene. It’s as if Tavenraat sensed the weight of history pressing upon this seemingly serene locale. Perhaps it’s a comment about stewardship or even our hubris when reshaping natural space. Editor: Precisely. This is also the time of growing industrialization. Even within such a humble drawing we could ponder about the impact of agrarian labor, social classes, and how those without power constantly navigate changing ecosystems. There is beauty in the simplicity of Tavenraat’s drawing, but one should see what exists within this seeming tranquility. Curator: It's amazing how a few pencil strokes can open up such profound lines of thought. I think I now see Bergschenhoekse Polder with fresh eyes. Thanks for the history and analysis! Editor: My pleasure! There’s power when art is activated with theory and historical insight. Let's leave our listeners to unravel these nuances for themselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.