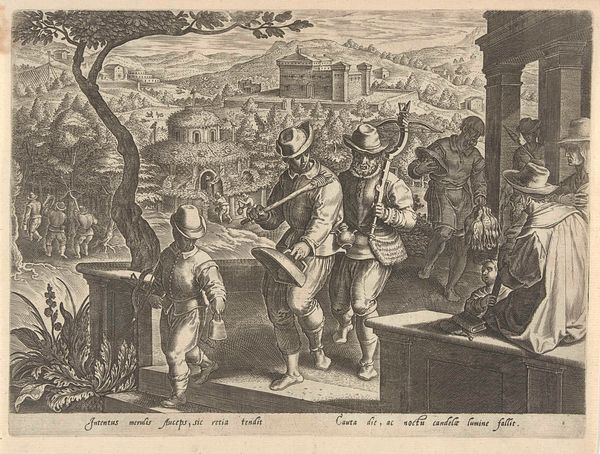

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 273 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to a striking engraving from the late 16th century, dating between 1594 and 1598. It’s entitled "Vrouwen verjagen een sater," or "Women chasing a Satyr," by Jan (II) Collaert, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It feels… intense. All that frantic energy etched into the scene, the clear foreground against the mountainous landscape. There is such distinct choreography to this chase. What medium are we seeing here? Curator: This is an engraving, so the materiality itself speaks to a printmaking process – the labor of incising lines into a metal plate. Look closely at the contrasting light and dark areas. It involved meticulously removing material, creating a reproducible image accessible to a wider audience than, say, an oil painting commissioned for a single wealthy patron. Editor: That accessibility is crucial. Consider the depiction of these women. They aren't passive figures; they are actively confronting, perhaps even punishing, the satyr. Is it about the perceived threat of unchecked male sexuality within a social order, reflecting broader anxieties about gender roles and female agency in the face of masculine power? I am also struck by the nudity in conjunction with weapon-carrying – is this to shame the satyr or elevate the women's position as somehow powerful in a pre-sexual era? Curator: It's fascinating how Collaert juxtaposes classical subject matter – satyrs are straight out of mythology – with the practical demands of print production. This print existed in a world driven by increasing access to art objects. It shows how reproductive techniques can spread and adapt traditional allegories or genre scenes for consumption in a quickly evolving market, democratizing art in its way. Editor: And that consumption, the cultural exchange inherent in its availability, allows for precisely these discussions we are having now! What social conversations do we think this imagery provoked during its contemporary consumption? Does the democratization come hand-in-hand with access for diverse audiences? Curator: Good point! Maybe, on this level, it provided a talking point – it could offer moral commentary on female virtue or simply titillate with a naughty scene and bare breasts, becoming absorbed into popular cultural understanding, impacting norms and expectations of art consumers through image availability. Editor: Agreed. Considering those competing layers enhances the way we see the piece now, reminding us that context truly shapes how we read not just the image but the historical moment it reflects. It all serves to inform our perceptions of women and social order – just like then, these threads stay woven into the tapestry of art-historical thought today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.