#

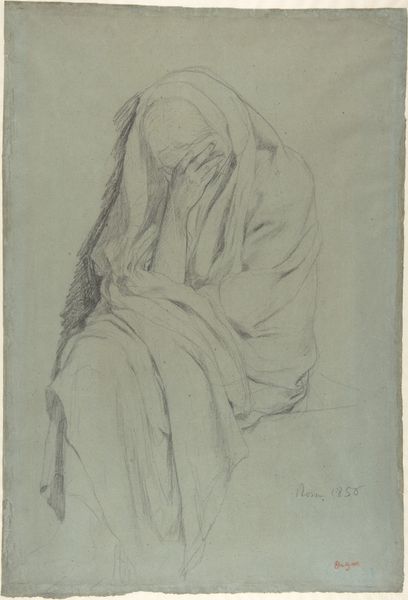

pencil drawn

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

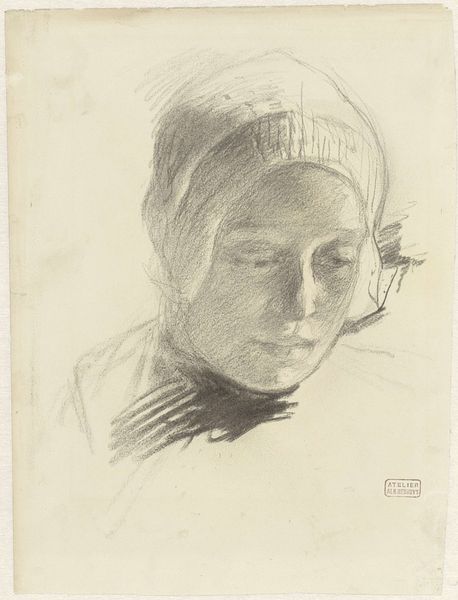

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

pencil drawing

#

sketchbook drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 349 mm, width 237 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

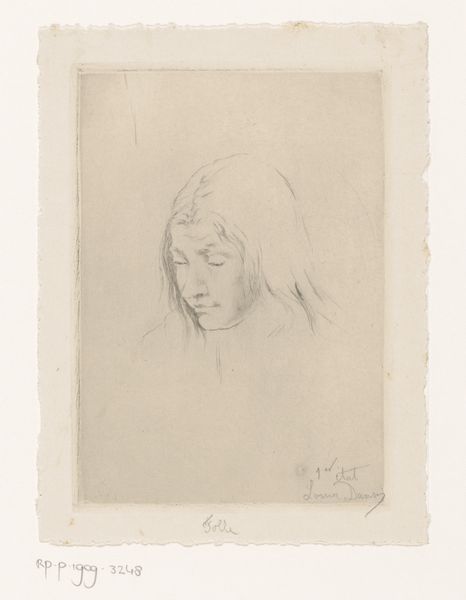

Editor: Here we have "Boerin met kap en doek," or "Farmer's Wife with Cap and Cloth," by Albert Neuhuys, created sometime between 1854 and 1914. It’s a pencil drawing on toned paper. The subject's downcast gaze and the muted tones give it a really somber feel. What strikes you most about it? Curator: The weight of generations, immediately. Notice how the cap and cloth, the very articles of clothing, act as both a literal and symbolic enclosure? They speak to a life lived within boundaries, both chosen and imposed, hinting at a cultural identity inextricably linked to the land and its hardships. Editor: I see what you mean. It’s like the clothing *is* the story. But it’s just a sketch; how much can we read into it? Curator: Sketches often reveal the raw emotional core, don’t you think? Neuhuys chose to depict not just a woman, but an archetype. Consider the significance of the downward gaze, a posture of humility, perhaps resignation, echoing centuries of rural life dictated by forces beyond individual control. What narratives do *you* find embedded in that posture? Editor: I guess it does invite a deeper consideration, especially when you consider how clothing can signify social standing and even cultural identity. I was only thinking about it formally. Curator: And that is valid. Now consider how our present gaze intersects with this past. What do *we* project onto this image? What does this image reflect back to us about our own cultural moment? Editor: Wow, I never thought about how much the viewer's background could shape the art's meaning. It definitely encourages more thoughtful observation. Curator: Precisely. Art becomes a dialogue, a conduit through which past and present continuously converse and challenge each other. The symbols resonate, shaped by the cultural memories we each bring.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.