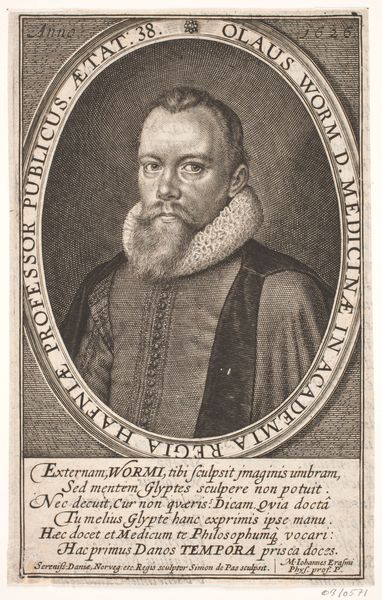

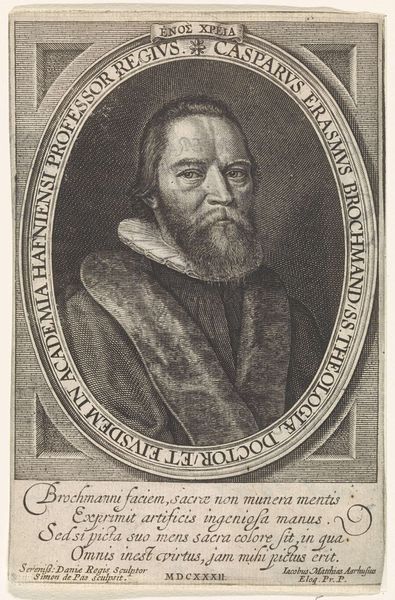

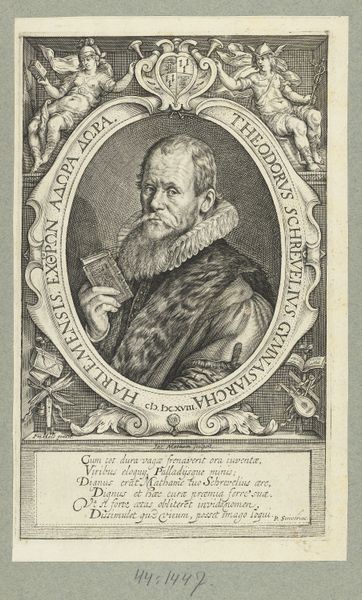

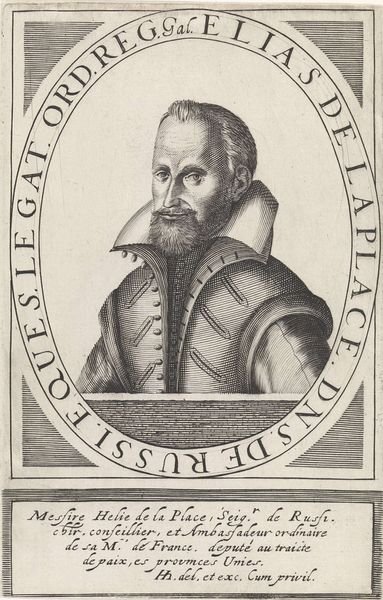

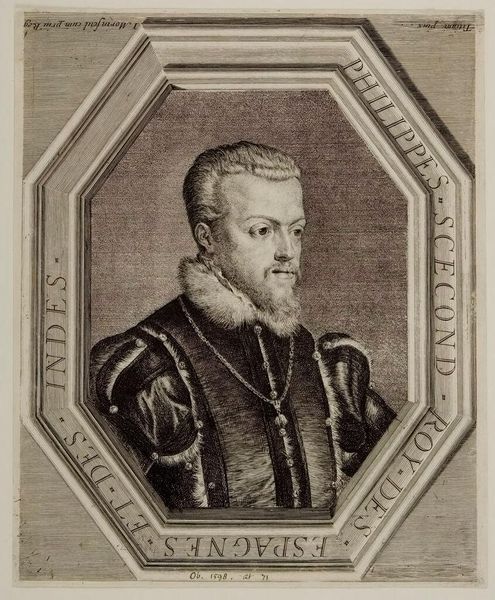

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: There's a real stoicism about this print, isn't there? So contained. So self-possessed. The detail… almost jewel-like. Editor: You're right; it does project a particular mood. For me, it's severity. Let’s contextualize the piece a bit. What we have here is a 17th-century engraving—the “Portret van Willem Lodewijk, graaf van Nassau-Dillenburg”—currently residing at the Rijksmuseum. It depicts William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg. Curator: It is anonymous, and I love that! Who gets to claim ownership? Maybe we all do? But regardless, that engraving, the detail on the ruff, the beard... It's such concentrated labor, rendered so precise. The sitter’s gaze almost pins you to the spot. A starched soul. Editor: And deliberately so, I think. Engravings such as this circulated widely, effectively performing early image politics. William Louis, cousin of William of Orange, was a key figure in the Dutch Revolt. The clean lines and formality served to project authority and strength to solidify his public image. Curator: Image politics... that feels so strategic and almost... well, calculating. I tend to look at portraits—especially these older ones—and wonder, what was the mood in the studio that day? Were they playing music? What did they talk about? The artist had to know they were making history, right? Did it give them butterflies? Editor: They were certainly aware of the stakes. Printmaking was integral to Dutch identity in the 17th century. It allowed for widespread dissemination of images and ideas, cultivating public sentiment. Think of these portraits not as capturing a fleeting moment but constructing a lasting symbol of leadership during turbulent times. Curator: Symbols… always symbols. Sometimes, I feel like my eyes are too slow. Too ready to be caught up in the detail, and I miss what everyone wants to read from it. It’s not that the history isn't interesting; it’s that… I want to feel the history instead. I want to know what it was *like.* Editor: I understand completely. But perhaps appreciating how these images were crafted to influence viewers centuries ago gives us a sharper understanding of how visual culture functions in our world today. It allows a little bit of empathy to enter the soul...a window. Curator: A window indeed... leading straight into a well-defended heart. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.