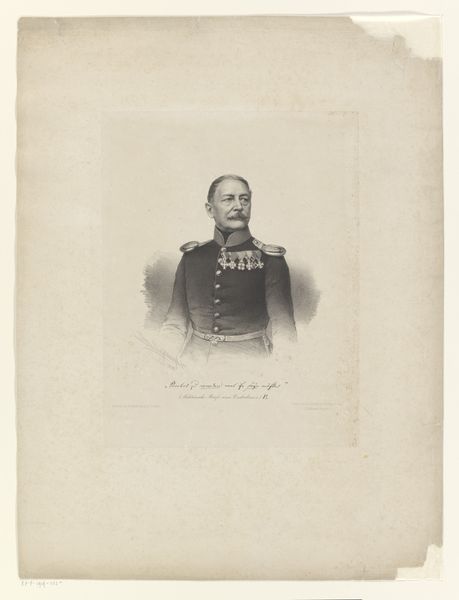

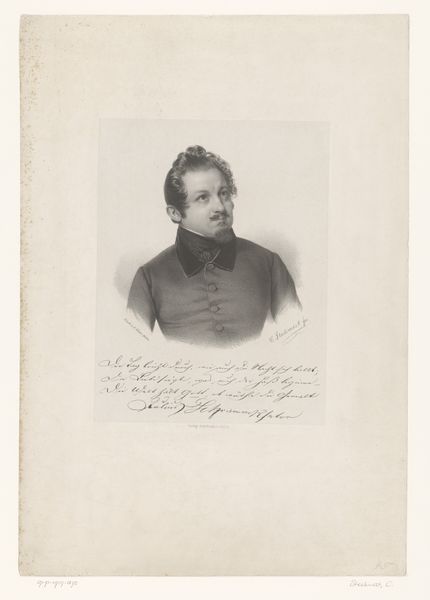

drawing, engraving

#

portrait

#

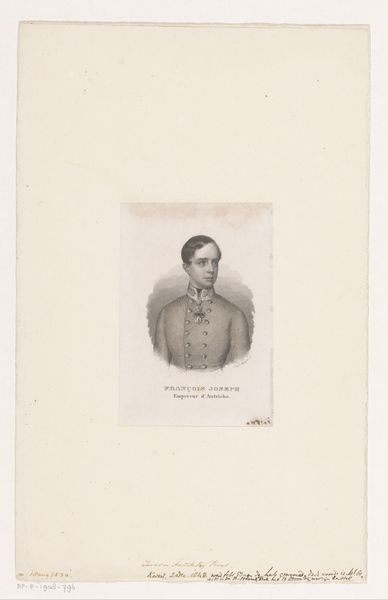

drawing

#

light coloured

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

romanticism

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 286 mm, width 241 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portret van een onbekende man, mogelijk Bucher," or "Portrait of an unknown man, possibly Bucher," by Jean-Baptiste Madou. Created sometime between 1806 and 1877, this artwork is an engraving. Editor: My immediate impression is one of constraint, almost melancholy. The light color and tight composition lend an air of formality and perhaps even repression to the subject's image. He is isolated on this white background. Curator: That resonates with its social context. Consider the function of portraiture in the 19th century. Beyond mere representation, portraits were crucial tools for constructing identity and projecting social standing, particularly within emerging bourgeois culture. This engraving’s precise lines reflect an ambition to portray social stature and propriety. Editor: Yes, there's a deliberate effort here. The military attire, the controlled posture – it's a performance of masculinity within a system designed to uphold particular power structures. The light and shadow play on the uniform and face, suggesting an internal conflict. It hints at the tension between public image and private self, doesn’t it? Curator: Absolutely, but I see the social coding running even deeper. If this is indeed Bucher, the uniform not only denotes military service but also symbolizes his allegiance to state power and potentially, colonialism and suppression, depending on his specific role. It invites a critical look at how the machinery of state co-opts individual identity. How might ideas of nationhood and imperial power impact the subject's experience of himself? Editor: It becomes a poignant visual statement, reminding us that portraits are not innocent depictions but complex negotiations between artist, subject, and society. These early photographic methods democratized the process, allowing a wider class of men—and, eventually, women—access to modes of visual representation they'd been excluded from. And as an engraving it democratized even further image making possibilities, correct? Curator: Indeed. The engraving itself allows for wider distribution of the image, furthering this play of visibility and influence. I appreciate the depth this reading allows us to understand the individual stories but their relationship with their sociohistorical circumstances. Editor: It changes our view from seeing it only as an artistic creation, but as something that truly has weight in a political environment. Curator: Precisely. It underscores the need to examine visual culture not as isolated artworks, but as active agents shaping perceptions, policies and even identities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.