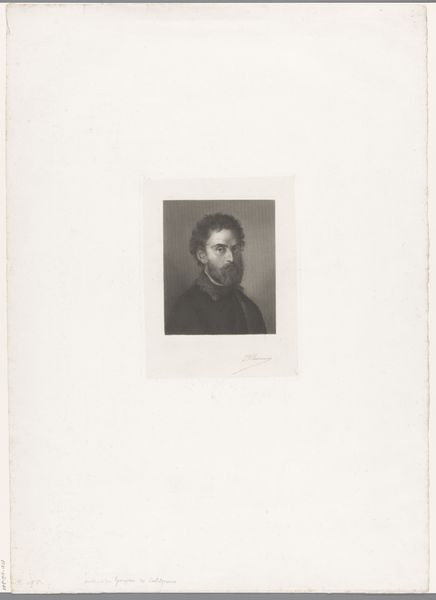

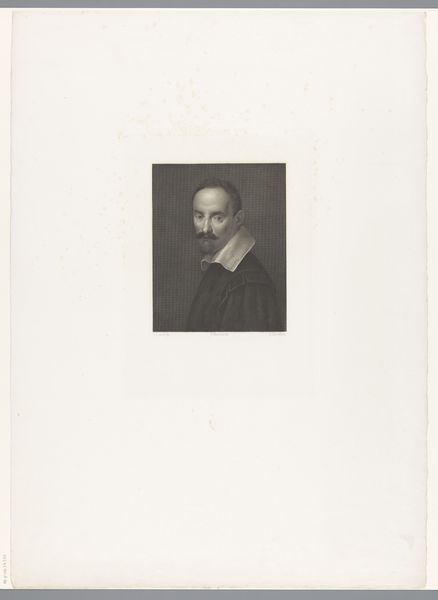

Dimensions: height 414 mm, width 295 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

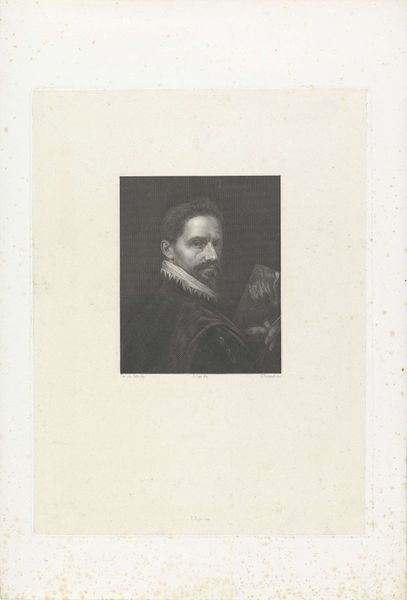

Curator: Ah, this engraving of Domenichino painted by himself...there's a vulnerability there that kind of grabs you, doesn't it? It's Charles Townley’s interpretation of baroque style, printed in 1778 using ink. It's really striking, isn't it? Editor: It certainly has a unique character, but the pervasive shadows create a melancholic tone. Note the strategic distribution of light and dark, creating chiaroscuro effect. It reminds us that engravings as prints are, in their very nature, contrasts: shadow and light, void and presence. Curator: Yeah, I think there's something lovely about how honest it feels, y’know? There are no attempts to, like, hide behind perfect lighting or flattering angles. Just this person looking right out at you, like he is in your room with you, almost 300 years after its conception. Editor: And let us consider what it means to ‘see’ or to ‘show’ an artist at work. The inclusion of what appears to be an engraving tool invites the viewer to actively imagine the creative processes—art about the process of creating art. Curator: It makes me wonder, what was it like back then? Were the tools themselves something to admire, maybe the only things some people ever owned that were of obvious quality? It is history in a frame, almost literally frozen and unmoving and existing perfectly as it did hundreds of years before. Editor: From a formal perspective, this also highlights something crucial about art. An image has both depth and surface and these formal structures invite the beholder to appreciate them actively. Notice too, if you will, the line quality. Curator: Totally. There’s a starkness about how Charles approached it that really amplifies the honesty in the original, y’know? It is hard, unflinching. He wants you to truly see the core of Domenichino in the barest medium possible. Almost an anti-Baroque. Editor: Baroque pieces often play with perspective and movement and the themes they evoke, but the simplicity presented here lends it an intellectual heft often missing in artwork from this era. What an illuminating print—pun very much intended.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.