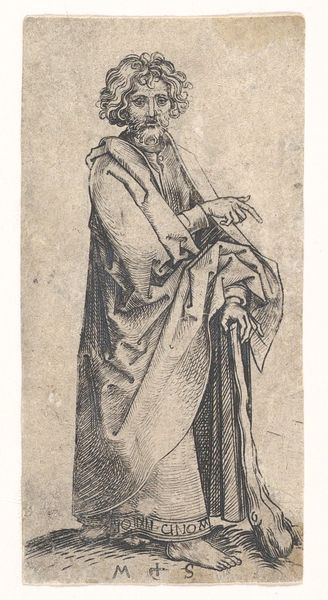

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

medieval

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 14.7 × 8.9 cm (5 13/16 × 3 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Let’s consider this engraving by Master ES, dating from around 1460 to 1465. It depicts the Apostle Simon Zelotes. The detail, achieved simply with line, is striking, don't you agree? Editor: It certainly has an intensity to it, stark almost, and slightly unnerving. The Apostle holds what appears to be a very large saw. I understand Simon Zelotes was martyred—is the saw somehow significant? Curator: The saw, indeed, became Simon's identifying attribute. Artistic depictions of saints often included specific objects connected to their lives, martyrdoms, or commonly associated miracles. For example, Saint Peter's keys. These became clear visual symbols for the largely illiterate population to recognize figures in Biblical narratives. Editor: So, the instrument of his death turns into his symbolic identity. It seems like a brutal abbreviation of a person’s life and belief into a single object, but such symbolic reduction, like a brand, clearly allowed for widespread identification. Curator: Precisely. Prints like these played a crucial role in shaping the cult of saints, disseminating their images across Europe. Master ES was very important in popularizing certain iconographies. Consider the cultural impact of images—how easily an agreed symbol can be shared and interpreted. Editor: The Apostle also has a halo above his head. He has this incredibly solemn look, holding that enormous saw like a burden. There's a gravity to the whole figure despite the simplicity of line and relative lack of ornamentation. Curator: Master ES had to carefully arrange a composition using almost exclusively linear means to convey a maximum of narrative and religious meaning. Think about this print circulating, quite possibly being hand-colored, in an era of intense religious observance, amidst shifting power structures within the church. These images were so politically potent. Editor: Yes, it seems to me to be less a portrait and more a visual abbreviation—emblematic, instantly readable for its intended audience. These saints were examples, paradigms, each instantly distinguished by these gruesome identifiers, constantly reminding the medieval public about their potential gruesome demise if they fell afoul of churchly politics. Curator: A chillingly effective application of symbolic imagery that was tied up in so many sociopolitical layers of 15th century Europe, so we've touched on how complex this simple seeming image is, hopefully, now listeners can appreciate it as we do. Editor: Indeed. Looking closely, the lines become powerful conveyors of stories that are both immediately readable and subtly deep.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.