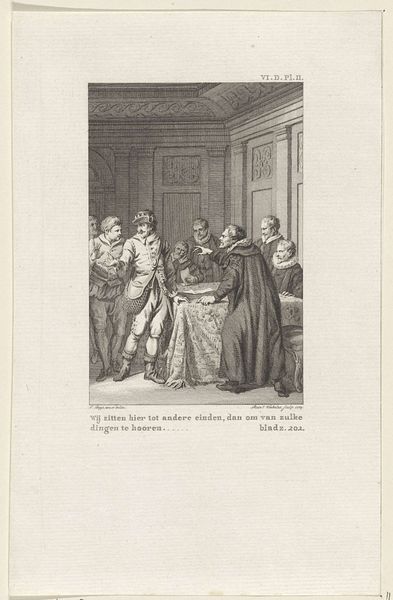

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

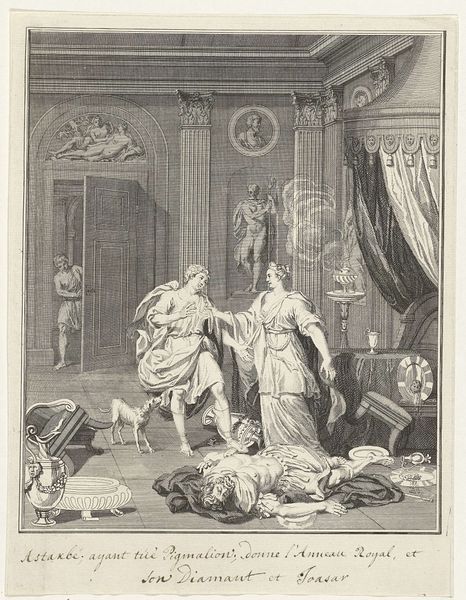

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

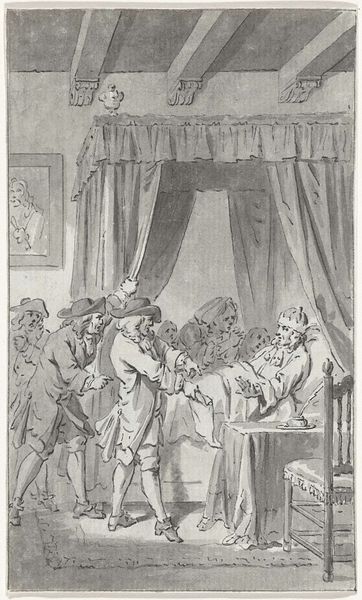

Editor: This is "The Murder of William of Orange, 1584", an engraving by François van Bleyswijck, likely created between 1681 and 1746. The drama! The moment captured is just...violent. The stark contrast created by the engraving technique really heightens the tension, wouldn't you agree? How do we begin to unpack the historical weight and artistic intent here? Curator: Indeed, the image's power lies not just in its depiction of violence but also its staging within a politically charged landscape. Engravings like these were often commissioned and disseminated to shape public opinion, weren’t they? How do you see this particular image functioning in terms of constructing a narrative around William of Orange? Editor: I guess it’s trying to paint him as a martyr? The assassin is right there, gun smoking, but William is elevated on the stairs, seemingly caught in a moment of leadership despite the attack. Does the location - is that Delft behind them? - play into this narrative, and the whole idea of nationhood being constructed? Curator: Precisely. Delft becomes a backdrop, a stage even, for this political drama. Consider the intended audience and what this location signifies for them. Wouldn’t you say that prints like these were powerful tools in the hands of those trying to build and solidify a Dutch identity and rally people to the cause, especially given William's prominent role? Editor: It makes so much sense when you frame it like that. It’s more than just art; it’s a calculated piece of propaganda, using both imagery and location to stir up feelings and create a sense of shared national identity. The narrative literally being *engraved* onto the collective consciousness. Curator: Exactly. It pushes us to think about the social function of art, its role in shaping public memory and political agendas. Images, and particularly widely disseminated prints, became key tools to forge a public identity. It certainly made me consider who exactly art served then, and how images shape beliefs. Editor: And, perhaps even more critically, it begs the question: whom does art serve today? Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.