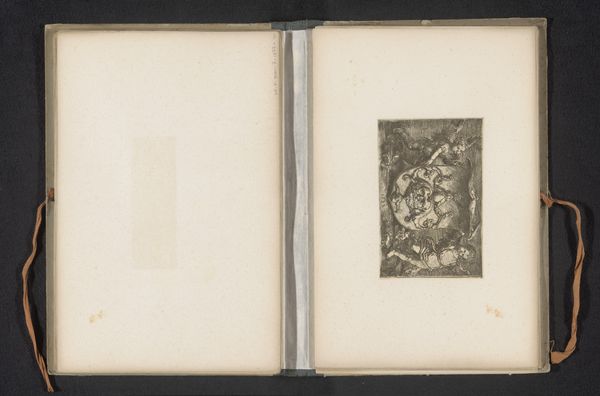

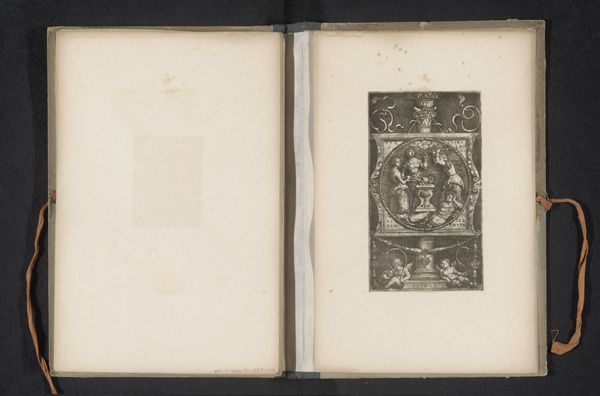

Reproductie van een prent van groteske ornamenten door Hans Sebald Beham before 1871

0:00

0:00

simonautoovey

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ornament, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

ornament

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 27 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, here we have an intriguing item from before 1871 in the Rijksmuseum collection. It’s a reproduction of a print showcasing grotesque ornaments, originally by Hans Sebald Beham. Editor: It looks like a secret language… Or the start of one, anyway. This lone image set against so much empty space feels deliberately placed, like a singular thought in a whole blank notebook. Curator: That negative space is powerful, isn’t it? These kinds of prints played a key role in disseminating artistic ideas during the Renaissance. Beham and other artists created these ornamental designs which were then used by artisans—goldsmiths, sculptors—to decorate all sorts of objects. It’s a really interesting case study of how art impacts the broader culture. Editor: And yet, within that rigid social role, I see playfulness. "Grotesque" feels apt here. The forms seem pulled and stretched, creatures barely holding themselves together, grinning. It has that Northern Renaissance macabre streak. Does that dark whimsy also fit within the historical context? Curator: Absolutely. These "grotesques" were often deliberately absurd, inversions of classical forms. Think of them as a visual rebellion against perfect symmetry and proportion. They provided an outlet, a safe space to explore the irrational. In a time of strict social hierarchies, the grotesque allowed for symbolic inversions of power. Editor: So it's sanctioned chaos, almost? Like a controlled burn to prevent a bigger fire. It feels incredibly relevant even now. Sometimes, the only way to deal with the overwhelming is to distort it, to poke fun at it. I am wondering what Beham's state of mind was when he put the design on paper and its correlation with social events happening at the time. Curator: Well, looking at the social upheavals of the 16th century with the rise of Protestantism and the peasant wars, you see how these grotesque designs gained even more significance as tools for visual satire and social commentary. The artists were indeed living and working in an era marked by rapid and disruptive changes. This certainly affected Hans Sebald Beham himself since he was exiled from Nuremberg. Editor: Incredible. The idea that something seemingly as simple as ornament could carry such weight. The object here looks to be more about the relationship between this dark yet also beautiful pattern against an infinite array of opportunities on the paper to expand, and perhaps express more. Curator: It’s a potent reminder that even what appears to be mere decoration is steeped in cultural meaning. And the reproductive print ensures these ornamental ideas never vanished and evolved through time! Editor: That makes me rethink my first impressions. What started as seeming chaotic, or rebellious actually feels carefully constructed, maybe even cautiously executed in a world demanding the complete opposite. Curator: Exactly. Art never exists in a vacuum. Understanding the conditions that produce it is essential to appreciating its true power. Editor: Food for thought then!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.