photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

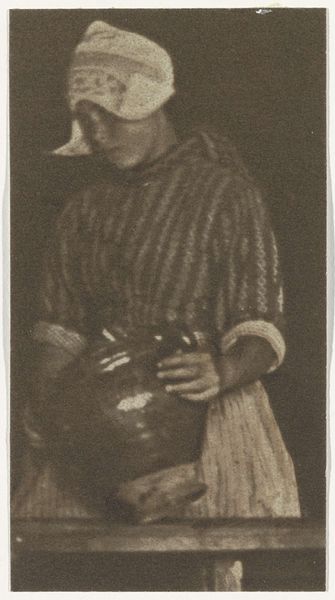

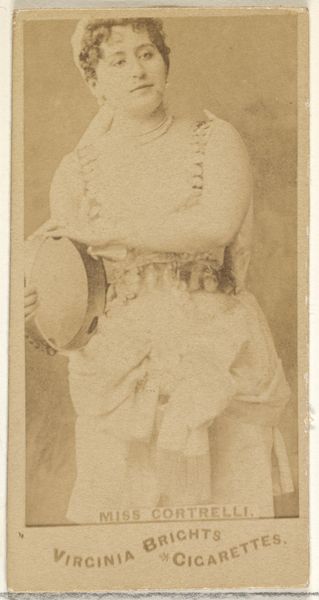

Curator: Hill and Adamson’s calotype, titled “Newhaven Fishwife,” made between 1843 and 1847, captures a moment in the daily life of a working woman. This salt print photograph currently resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately, the sepia tones give it such a sense of history, almost like peering through a faded dream. There’s something both strong and vulnerable about the woman’s gaze; she feels so present, you know? Curator: Absolutely. Photography during this period, particularly the calotype process, allowed for a degree of realism previously unseen. However, we have to also remember the power dynamics inherent in image-making during this period, particularly concerning gender and class. Who gets represented, how, and why. Editor: True, true. It feels like she's posed, and yet there is this quiet intimacy. I almost want to write a poem about it, something about the sea's strength being mirrored in her posture and steady look. The folds of her dress and that basket she carries seem full of unspoken stories, salt, labor, all the while thinking "Who am I here beyond her gaze and her basket?". Curator: Those stories are undoubtedly complex. As we analyze this portrait, we also confront questions around representation of working-class women. For instance, how do her clothes and stance impact our reading of her socio-economic position and labor within the societal framework of Victorian Scotland? Editor: Maybe the art is the negotiation with it, her negotiation as much as theirs! That’s why this work is so alive and keeps me searching to feel her within this space as she is forever carrying. Curator: Agreed. What is so striking is precisely that tension. Hill and Adamson crafted this piece amidst a burgeoning industrial era, reflecting evolving views on both art and the laboring classes. It encourages ongoing interrogation of gender, class and early photography. Editor: For me, it's an emotional experience as much as an intellectual one. The muted light, her half-smile, everything is inviting you to join, or complete a moment, to bring yourself in. Curator: This photographic work leaves a lasting impact—pushing beyond straightforward representation toward something far more profound, a nuanced and, perhaps still opaque narrative of life in 19th-century Scotland. Editor: Precisely, I'm left thinking about her and feeling this echo. That’s what keeps art breathing— it becomes an invitation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.