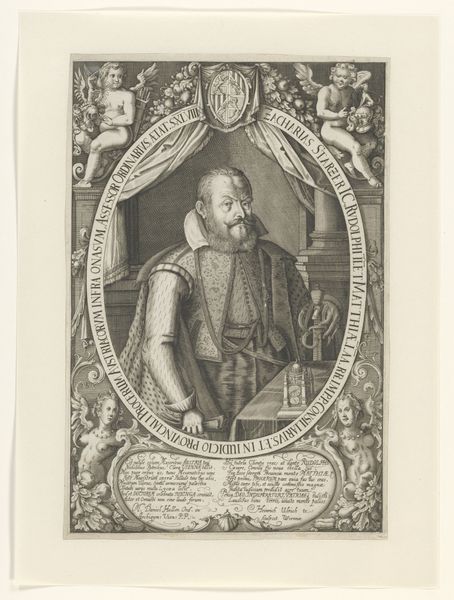

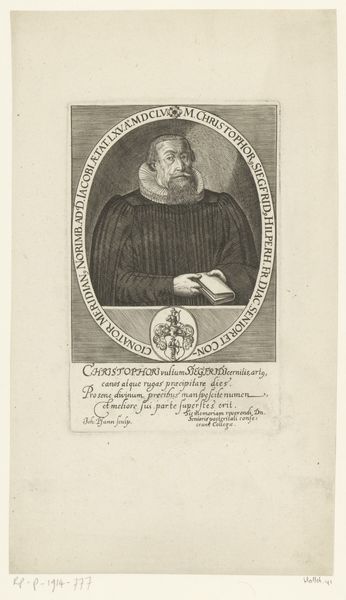

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 256 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Portret van Andreas Kunad," created in 1661 by Johann Caspar Hoeckner. It’s an engraving, quite detailed. There's a stern quality to it, befitting someone of obvious stature, maybe even self-importance. I'm struck by the elaborate collar! How do you interpret this work? Curator: Beyond the elaborate collar – a marker of status, certainly – let's consider the social and intellectual landscape of the time. Here’s Kunad, a rector and professor. How might his position have shaped his identity, and, subsequently, the portrait itself? Editor: He looks… scholarly? The books imply that, of course, and the severe gaze. Maybe he’s trying to convey authority? Curator: Precisely. It’s not merely about conveying authority, though. This image enters a broader conversation of power and representation. Who had the means to commission or create such portraits? Whose voices were amplified, and whose were silenced in 17th-century academic and religious spheres? Consider the text surrounding him—aren't these affirmations of his worthiness and intellect reinforcing very specific, likely exclusionary, power structures? Editor: So, by focusing on the historical context, we can start to understand not just who he was but what power structures were at play when this portrait was made? Curator: Exactly! By looking at portraiture through a lens that examines social, political, and economic forces, we see beyond the individual and begin to analyze broader societal values and biases. What does it mean to memorialize THIS man in THIS way, at THIS time? Editor: I hadn’t considered all the layers embedded in a portrait like this. I'm rethinking what portraiture can communicate! Curator: And that’s the beauty of art history. It's about engaging in an ongoing dialogue with the past, questioning narratives, and acknowledging whose stories get told—and whose don’t.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.