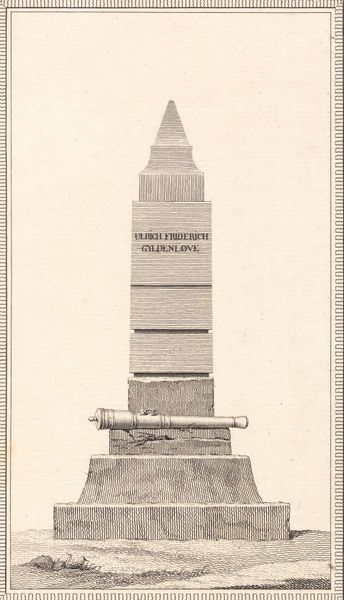

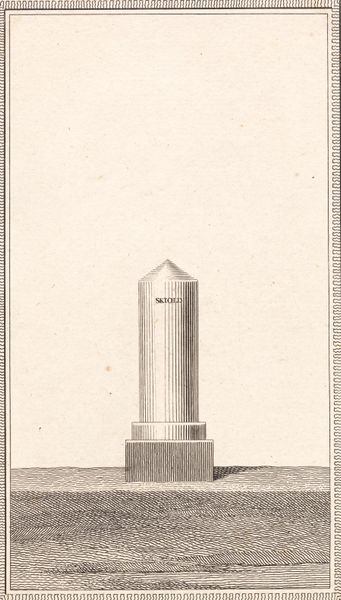

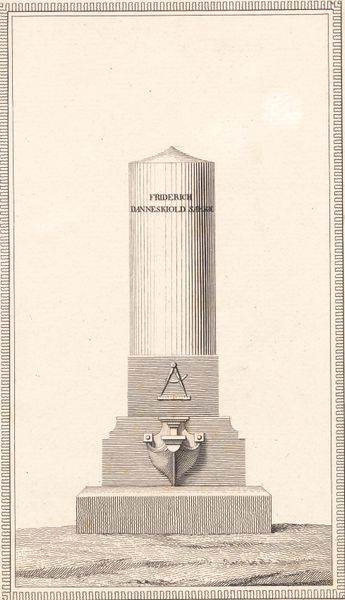

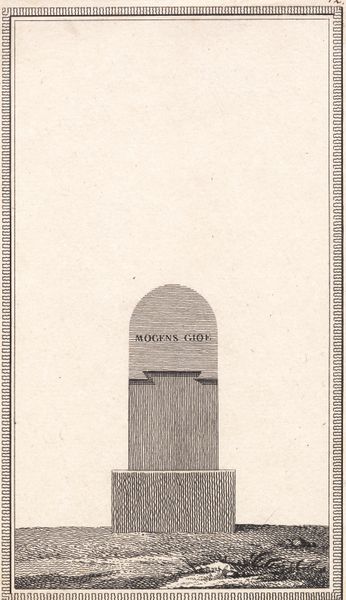

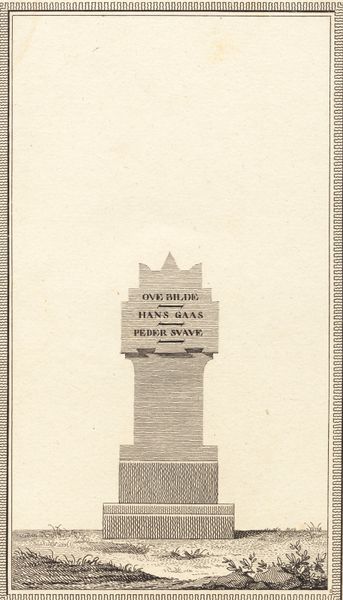

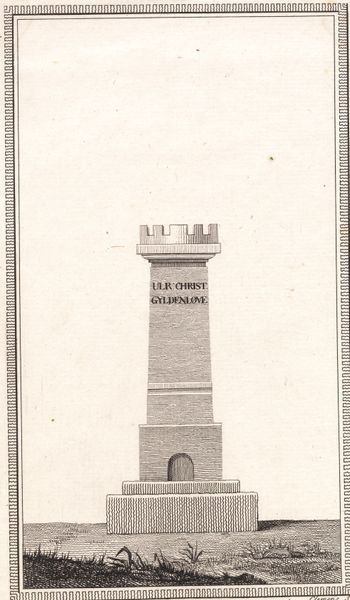

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

line

#

cityscape

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: 179 mm (height) x 103 mm (width) (billedmaal)

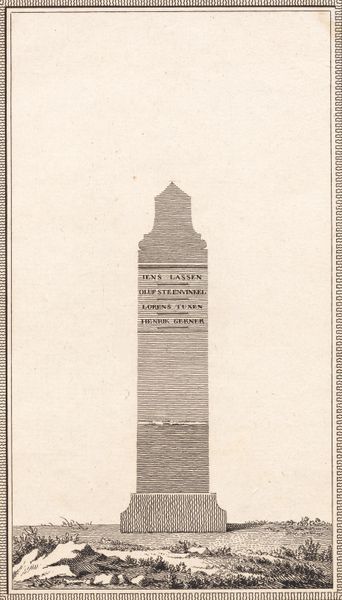

Editor: Here we have J.F. Clemens' "Daniel Rantzau", an etching from around 1780. It depicts a tall, thin obelisk rising from a stepped base. It feels…severe, almost oppressively simple. What’s your take on this print? Curator: This work, seen through a materialist lens, begs the question: what function did prints serve? Etchings like this made imagery widely accessible. Instead of unique, handcrafted monuments, we get a mass-produced *representation* of one. What does this say about commemorating power and status in the late 18th century? Editor: So you’re saying it's less about the specific person, Daniel Rantzau, and more about the act of memorializing *itself* being democratized through printmaking? Curator: Exactly! Consider the labor involved. An engraver meticulously carves the image into a plate, then countless prints are pulled. How does the repetition of this process affect the meaning of the image, and the consumption of imagery? Does it dilute the commemoration, or amplify it by sheer ubiquity? Editor: I see your point. I was focused on the stark visual, but you've shifted my perspective to the *means* of its creation. Curator: It is interesting to consider if the artist had ever seen the monument themself. Could the act of representing be as important, or more, as the presence of the obelisk it represents? Editor: It's fascinating how something that appears so straightforward on the surface reveals so much about production and cultural consumption when we look at it that way. I’ll never see prints the same way again. Curator: Material concerns shape our understanding. Now we must consider, where were these sold, to whom, and why?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.