painting, oil-paint

#

16_19th-century

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil painting

#

fruit

#

realism

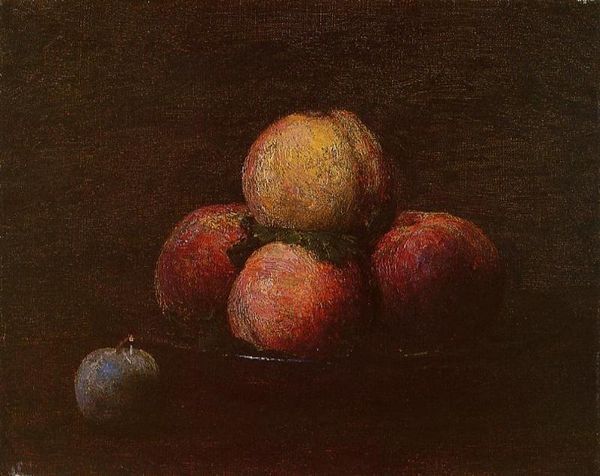

Dimensions: 61 x 44.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Gustave Courbet’s “Still Life with Apples and Pomegranates,” created in 1871, presents us with a bountiful, though rather earthy, collection of fruit arranged in a simple bowl. The painting is currently housed here at the National Gallery. Editor: My first impression is one of ripe abundance verging on decay. The colours are rich but muted, with a strong emphasis on browns and reds. It's as though Courbet captured the very moment of ripeness, the peak before inevitable decline. There's an intensity in its stillness, like holding your breath. Curator: That feeling of 'decline' isn't accidental, I think. Within the broader scope of art history, still lifes carry powerful Vanitas symbolism. Here, fruit stands for harvest and life’s bounty, but simultaneously foreshadows its transience, the inescapable fading of beauty, particularly during a period of immense sociopolitical turmoil in France. The pomegranates, in some traditions, are a complex sign of fertility, death, and resurrection. Editor: That context is crucial. This work appears near the end of Courbet’s career; during this time, the political atmosphere and social upheaval of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune certainly impacted his art. It raises questions: is he merely presenting objects, or reflecting on ideas of sustenance, decay, and, given his politics, the fragility of social order? The metal pitcher in the background strikes a cold, industrial contrast to the organic forms of the fruit; perhaps speaking to the industrial encroachment on the agrarian. Curator: Absolutely. This contrast creates tension. I think it represents not only physical realities of daily life during his time but, like a psychological portrait, captures how societal transformation affects perception of time and reality. It encourages viewers to reflect on both our contemporary sociopolitical state of affairs and human relationship with time. Editor: In the painting’s emphasis on real-world subjects—fruit and kitchenware, handled with his characteristic directness, devoid of idealization, we observe a powerful social message. Even the muted colours suggest something more real, perhaps even a call for society to return to basic essentials. This piece pushes us to understand the stories objects can tell about our lives and broader societal forces. Curator: A return to origins, perhaps, to fundamental human symbols. Looking at this, I also reconsider cycles: artistic cycles, the return to classic forms, or a personal return to simpler themes following major personal events or periods of historical change. It adds another layer to our observation of time and reality. Editor: Indeed. It also seems this painting speaks as much about historical shifts and Courbet’s personal history, challenging viewers to perceive art and life through an intricate web of interwoven themes. Curator: Well, after delving deeper, it seems Courbet offered us much more than simply apples and pomegranates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.