painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

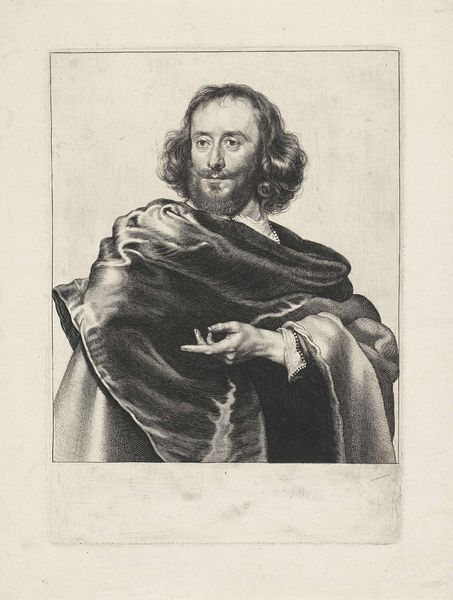

Curator: Here we have Nicolaes Maes’s "Portrait of a Man," created sometime between 1650 and 1660. Its somber mood is striking, don’t you think? Editor: Indeed. Immediately, my eye is drawn to the way the impasto captures the heavy woolen cloak, and the tight weave of the under-sleeves beneath, alluding to a social standing interwoven with skilled labour. Curator: Observe the meticulous detailing of the face. The subject's gaze and posture invites analysis—it seems almost staged within its realistic qualities, adhering, naturally, to many principles of Baroque portraiture, although the realism gestures towards other considerations too. Editor: Staged perhaps, but let's not dismiss the artist's materials: where were pigments sourced, what was the ratio of binder to pigment to yield the translucent depths? Was this canvas made by a specialist workshop and the implications this held within Dutch guild society? The man might have had someone handcraft his coat, someone else make his bands, someone prepare Maes' supports—labor everywhere that painting smooths away. Curator: Fair points. Nevertheless, the play of light and shadow across his brow creates a dramatic tension, reflecting the internal state we’re asked to contemplate. Note, too, how that small amount of light throws up the rich texture. Editor: Agreed, and the quality and weight of these pigments affects its visual experience to say the least! What was affordable, and who afforded it, I ask? Even if not an explicit commission of display of mercantile power, this is most likely of merchant origins at the very least. It does suggest an aspiration and integration of bourgeois values too though. Curator: So, despite this painting's formal elements initially suggesting an interiority and character analysis of an individual—the semiotics of color, posture, expression, do seem deliberate—your contextual reading reminds us of the painting's connections to the economic and labour frameworks of 17th-century Dutch society. Editor: Exactly. And vice versa! His careful, clean presentation also subtly elevates everyday life. Material realities in art always work to construct a kind of story – this Dutch story makes me look harder for the hidden labor of those involved in that moment. Curator: That’s a compelling connection to explore; I am forced to reconsider my more focused readings in lieu of a wider, and material, historical lens. Editor: Yes, our dual scrutiny has broadened and refined a deeper narrative, hasn’t it? I certainly have much more food for thought!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.