drawing, print, etching, ink, charcoal

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

impressionism

#

etching

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

horse

#

charcoal

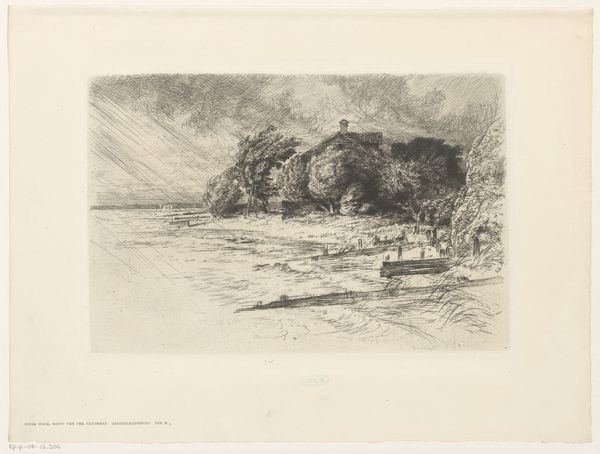

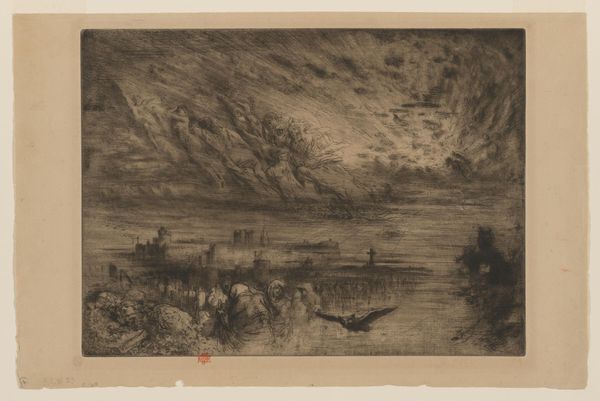

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We are looking at Félix Hilaire Buhot’s print titled "Onweer", likely created between 1857 and 1898. It’s currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. The artist employed a range of techniques: etching, drawing, and working with ink and charcoal to depict this landscape. My first impression: there is a sense of urgency to the composition with the large cloud formations, which have a sense of darkness about them. Editor: The visual weight definitely pulls me into that sky. This is an intriguing mix of delicacy and force. Considering Buhot’s involvement with Impressionism, it's tempting to connect this weather scene to broader anxieties around industrialization, especially climate change. The rural landscape here almost becomes a stage for modern ecological drama, a space threatened by larger, unseen forces. The figures feel so small, they appear overwhelmed by what's looming over them. Curator: Absolutely. You can read a tension into this work in terms of humankind versus nature, that struggle plays into an even older visual vocabulary. Take, for instance, the presence of storm clouds and windswept trees, evoking established symbols of turmoil. Think, the deluge, the wrath of God, nature's indomitable will... Are those biblical overtones in conflict with the era’s burgeoning scientific rationality, do you think? Editor: Perhaps there’s an integration there, not necessarily a conflict. Consider that during the period of the "Onweer"'s creation, natural disasters became ever more politicized. The rapid developments of modernity demanded explanations and accountability, so to use the deluge as an artful backdrop perhaps infuses those conversations with greater historical nuance, and lends an interesting new edge to conversations on modern culpability. Curator: A very crucial point, I'd say, one that reminds us of art's unique position as a dialogue between the then and the now, speaking through signs, symbols and stories across generations. Editor: And it really reveals a certain contemporary thread, allowing a late nineteenth-century landscape to still resonate within a very twenty-first-century crisis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.