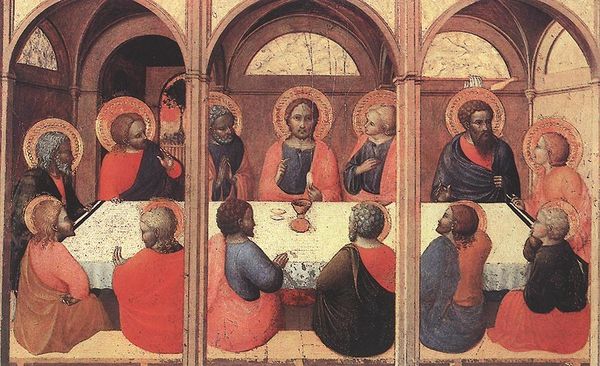

tempera, painting

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Overall, with engaged (modern) frame, 15 x 22 1/4 in. (38.1 x 56.5 cm); painted surface 13 1/2 x 20 3/4 in. (34.3 x 52.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Ugolino da Siena's "The Last Supper," painted around 1322 to 1333, using tempera. It’s… well, it's certainly a unique take on the iconic scene. It feels a little less dramatic, more like a somewhat awkward gathering. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond the immediate biblical narrative, I see a snapshot of medieval social dynamics and power structures reflected through a theological lens. Consider the figures' postures and halos: How do these visual cues establish a hierarchy? And how might this depiction reinforce societal norms of the time, particularly around faith and obedience? Editor: So you’re saying the painting is about more than just the Bible story itself? Curator: Exactly. The very act of depicting this sacred moment serves a purpose, one that often transcends pure religious devotion. It’s crucial to consider who commissioned the work, where it was displayed, and what message they hoped to convey to its viewers. What role does wealth and power play in the patronage of the art? Editor: I never really thought about it that way before. It's like the artist isn’t just illustrating a scene, but also making a statement about society. Curator: Precisely! Consider the marginalization of certain voices in both historical and contemporary tellings of religious narratives. Do you think this impacts how we receive art tied to theological subject matter? What stories do we not hear? Editor: This makes me think differently about history paintings in general, like there is always something left out! Curator: It is often in these omissions that the powerful presence of the oppressor and marginalized come into stark relief. Thanks for exploring that angle with me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.