#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

ink drawing

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

portrait drawing

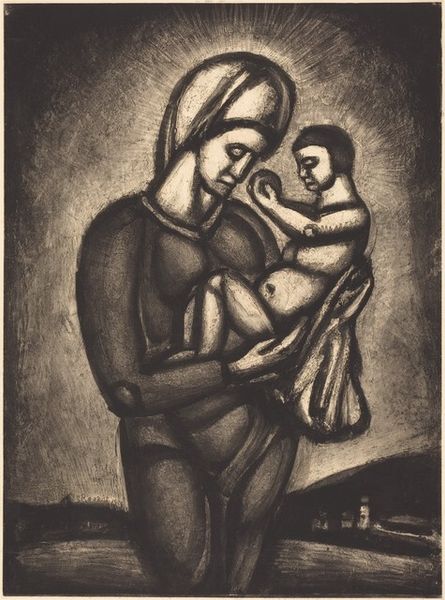

Dimensions: image: 34.61 × 25.08 cm (13 5/8 × 9 7/8 in.) sheet: 50.8 × 34.93 cm (20 × 13 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

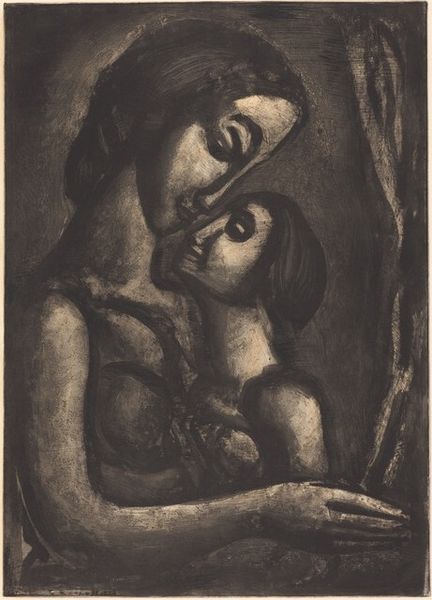

Curator: We’re standing in front of Georg Ehrlich’s "Pietà," created in 1923. It's a print, and strikes me as quite intimate in scale, almost like a personal meditation on grief. Editor: It’s emotionally charged, isn't it? The starkness of the ink combined with the rawness of the lines—it immediately conveys immense suffering. I see how the work, reminiscent of similar iterations across history, seems like a visual manifestation of mourning, something timeless. Curator: Precisely. And let's consider the socio-political climate of 1923, a time of significant upheaval in Europe following the First World War. Ehrlich, an Austrian Jewish artist, was deeply aware of the pervasive social anxieties and economic hardships. This "Pietà," therefore, is not just a religious image; it’s a powerful commentary on the profound sense of loss and displacement experienced by many after the war. It becomes a symbol for anyone affected by great distress. Editor: The formal arrangement bolsters that reading. The figures are huddled together in the foreground, but look at the skeletal, almost abstract quality to the figure’s faces. They suggest a world devoured by trauma. What do you think that compositional choice conveys, beyond a narrative of agony? Curator: It’s the stripping away of all non-essentials that leaves behind this visceral emotion. This echoes movements within expressionism during that time, to not simply depict but convey deeply subjective feelings. The formal qualities like line weight and texture help with this. Look closely at how the background fades into obscurity; that stylistic touch pushes the immediate feelings of the subjects, as well as their narrative, to the forefront. Ehrlich uses line as if to echo both emotional anguish and the search for understanding beyond traditional structures. Editor: The cyclical element of the print becomes unavoidable. You can't miss the art historical weight of the piece itself: motherhood, death, faith. Curator: True, and even within the formal representation, this particular arrangement underscores not only the inevitability of loss, but perhaps even a redemptive possibility. Editor: In the end, Ehrlich uses a historical language to depict something deeply personal. It invites contemplation on grief itself. Curator: A synthesis that elevates it to a poignant symbol.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.