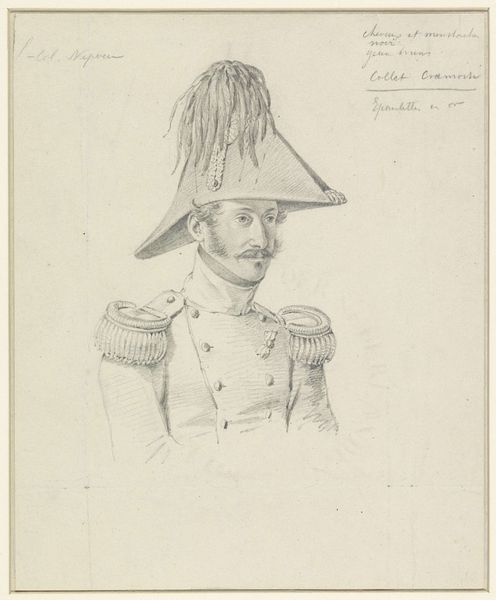

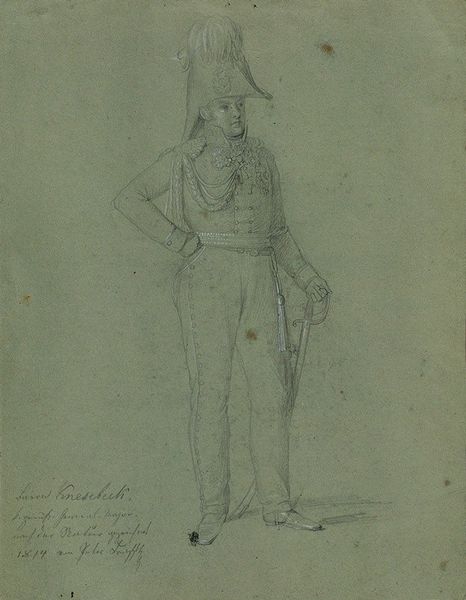

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

facial expression drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

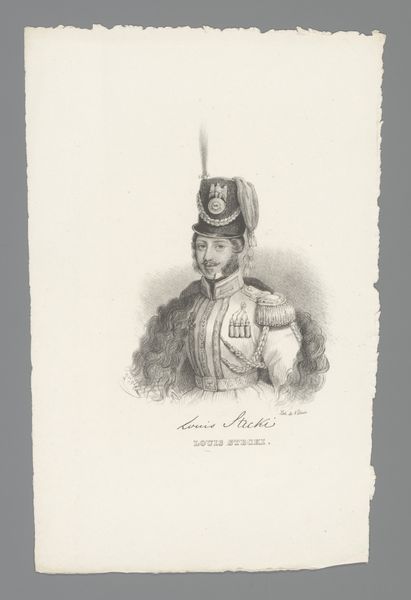

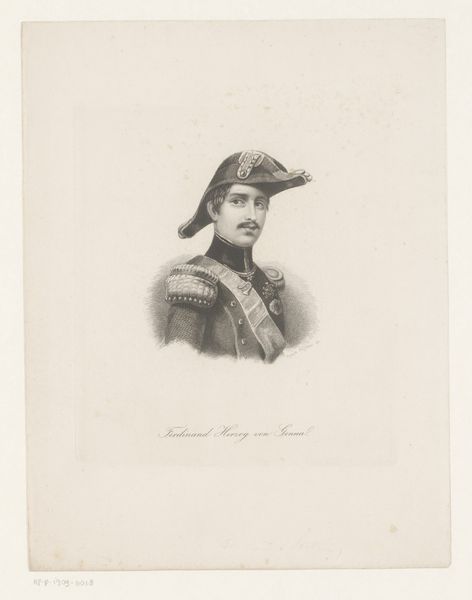

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jacob Joseph Eeckhout’s “Portret van Figuelmont,” a pencil drawing from the early to mid-1830s currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: There’s a kind of vulnerable austerity to it, isn’t there? The light pencil work almost softens the severity of his military dress. Curator: Precisely. The drawing is an intriguing artifact of the era, depicting a man, likely an officer given the uniform and embellishments. The artist, Eeckhout, was well-regarded for his portraiture, moving within the higher circles of society at that time. The level of detail in the facial features is rather striking. Editor: Absolutely. But looking closer, it also exposes something of the power structures inherent in portraiture. Figuelmont is portrayed with a rather grandiose feather headdress. This speaks volumes about class and status and about the role of the military and military portraits in upholding certain ideals during that period. Curator: And note the inscription above the subject’s head indicating specific colours like ‘plume noir’ (black plume) – those annotations were perhaps meant for a future colourist working on a full painted rendering, so possibly the portrait served a functional, pre-production purpose. Editor: Right. Those added notes and textual directions further expose the labour behind images like these, the layers of work often unseen in finished works, reinforcing how images don’t arise in a vacuum but from a space where many are involved. What did military service mean for someone like him, for his community? I’m very curious about that context. Curator: That's a valuable perspective, highlighting the portrait as a staged representation with a political and social purpose, well beyond pure likeness. The inscription points towards artistic practices of the time and provides material context. Editor: It also offers a small point of access. As an activist, I want to leverage any access I can get into historical material and put pressure on these historical hegemonies, bringing social awareness to the forefront, making history speak to a more democratic present and future. Curator: And through that social awareness, art engages directly with the concerns of contemporary audiences, fostering civic dialogue and helping people reconsider dominant cultural narratives and beliefs. Editor: Precisely. This image, with its quiet and intense presence, provokes important discussion about hierarchy, about labour, about what it means to look and be looked at.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.