drawing, ink, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

medieval

#

form

#

ink

#

pencil

#

line

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

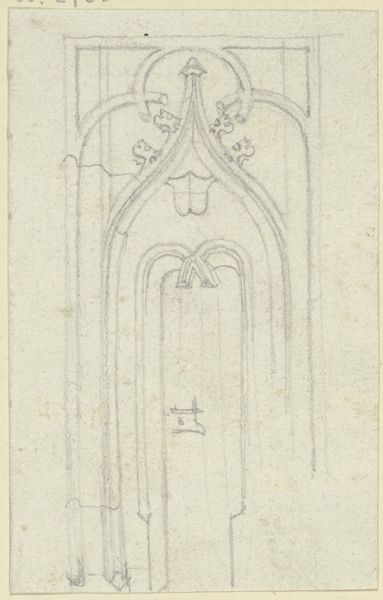

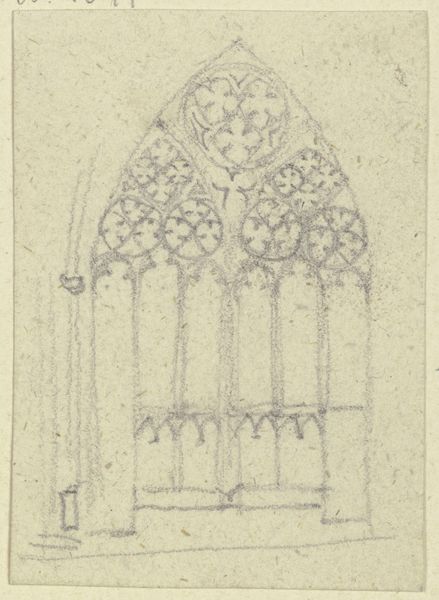

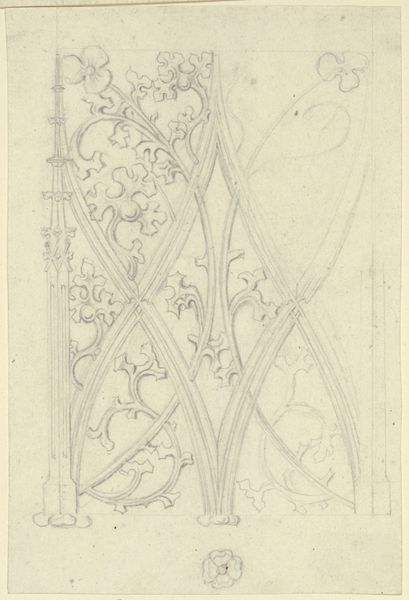

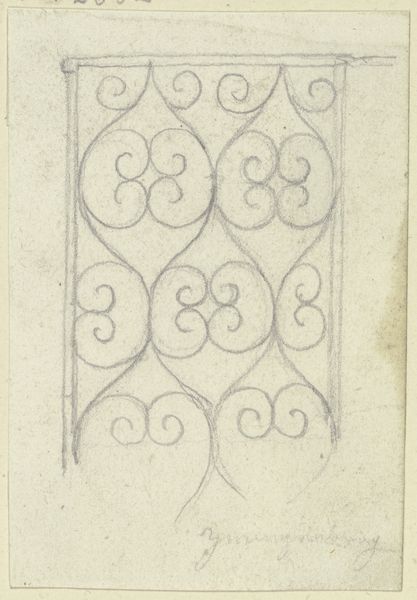

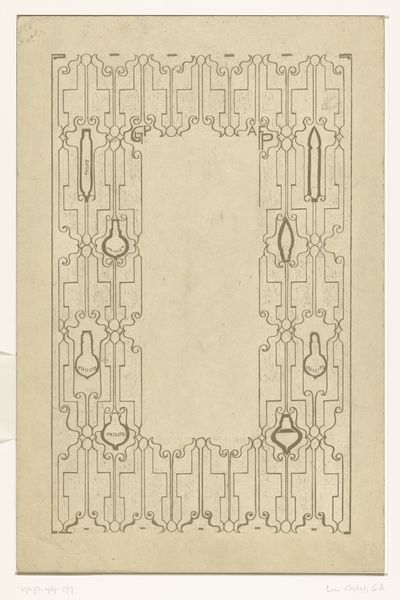

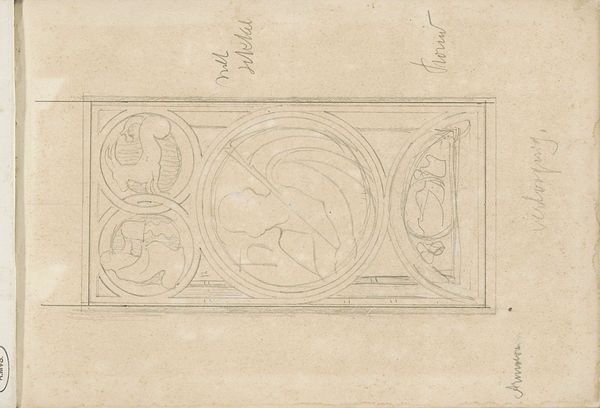

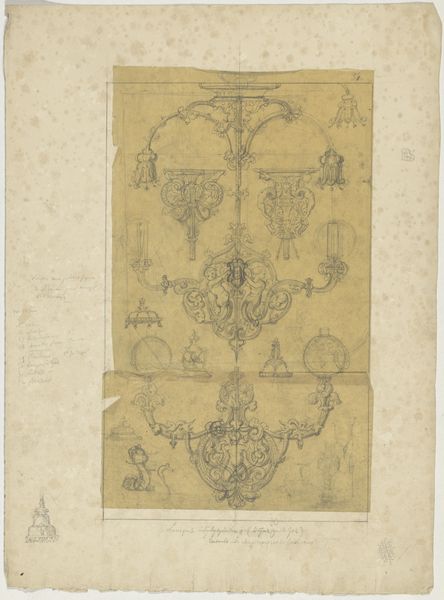

Curator: The drawing before us, entitled "Eisengitter sowie gotische Nase in einem Maßwerk", held at the Städel Museum, offers an intriguing study of Gothic architectural details. It's rendered in pencil and ink, focusing on line work to define form. Editor: It feels incomplete, almost ghostly, in its ethereal depiction of ironwork. You can see the hand of the artist through the varied line weights. Curator: Indeed. The work invites us to consider how such gothic forms echo deeper structural elements, like the pointed arch and the recurring trefoil, as symbols of aspiration and divine connection prevalent throughout medieval cathedrals. Do you find yourself reminded of anything similar? Editor: I'm most intrigued by the presumed social function of such highly crafted ironwork. We have an implied barrier between spaces, meant to safeguard while presenting beauty. This was both exclusive and highly visible. Did the craftsmen experience any conflict rendering art for this context? What access and materials were afforded to create these detailed lines? Curator: Those are incisive points. Thinking anthropologically, the iron grates represent a boundary that suggests ideas about sacred space, the separation of classes, and hierarchies made visual. The pointed "nase," as the title suggests, hints at both the ornamentation and, dare I say, the assertion of a specific architectural and cultural power. Editor: A barrier literally forged in the crucible of labor. And it's that forging—the actual labor process—that interests me. Think about the materials: iron extracted, processed, shaped under intense heat. Who managed these tasks, and under what conditions? This work gives us a beautiful product, but at what cost? Curator: Well, it’s undeniable that every mark here has resonance far beyond geometry. This detailed rendering speaks not only to an artisan's observation of design, but evokes ideas about belief and societal structure—encoded meaning if you will. Editor: For me, looking closer I think there is something more. It provokes critical thinking about artistry, the exploitation of labor, and access, especially at the confluence of "high" design. It really comes down to interrogating these narratives. Curator: It does underscore, quite literally, how aesthetic appreciation intersects with larger historical frameworks of material reality and belief systems. It really holds a special mirror up to both craftsmanship and ideology. Editor: Definitely, a powerful lens through which we can reflect on cultural legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.