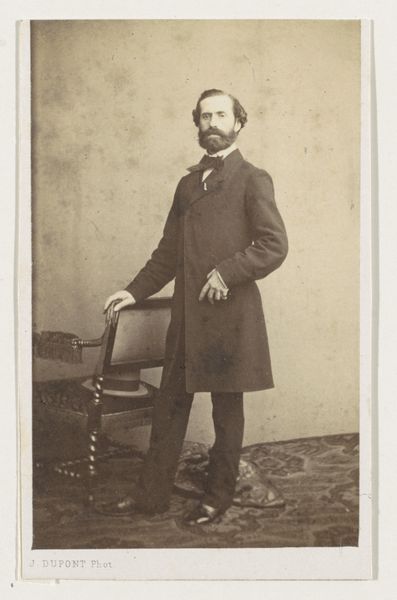

Dimensions: Image: 13.7 × 9.1 cm (13.7 × 9.1 cm), arched top Sheet: 14.2 × 9.6 cm (14.2 × 9.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

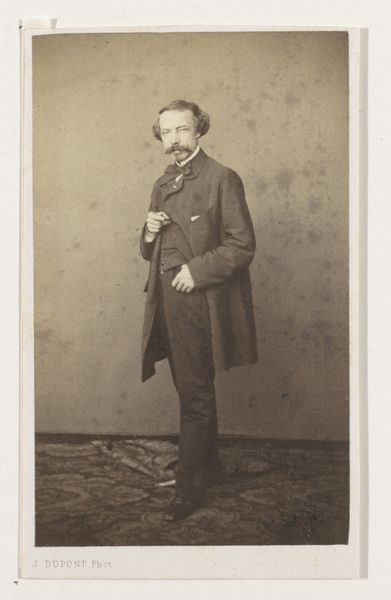

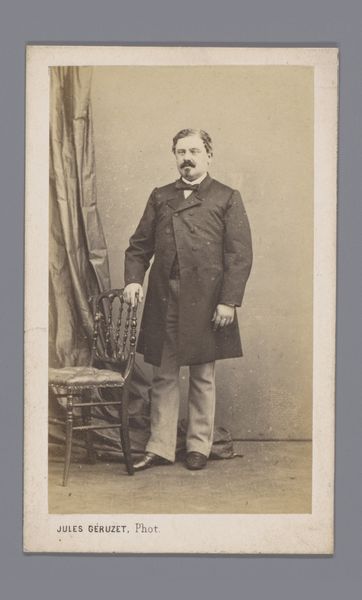

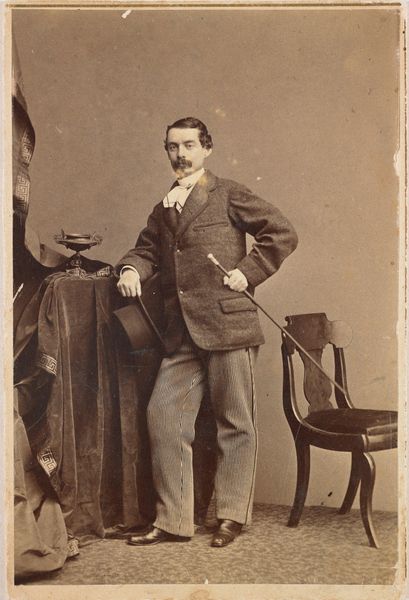

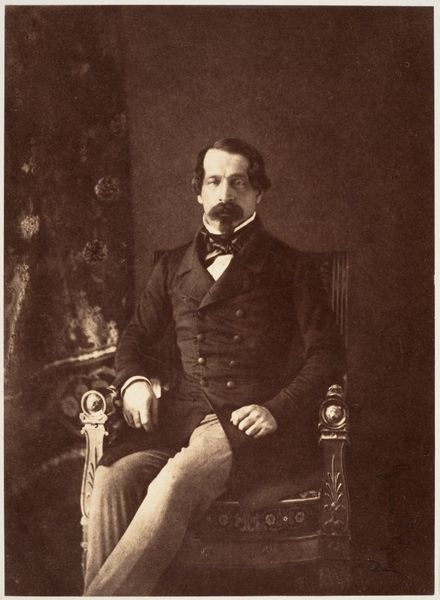

Editor: This daguerreotype from 1860 portrays Emperor Napoleon III. I’m struck by the formality and stiffness of the image; everything from the pose to the column feels incredibly staged. What stands out to you in this portrait? Curator: For me, it's about the material production of the image itself and its subsequent consumption. Consider the expense and time involved in creating a daguerreotype in 1860. Photography, still relatively new, was rapidly becoming a tool of the bourgeoisie. Editor: In what way was it a tool? Curator: Well, think about it. It democratized portraiture to some extent, but access to it was still determined by social class and capital. The labor involved – from the photographer, Olympe Aguado, to the assistants, the studio production - all represent a significant economic investment and a very conscious performance of power and status. Napoleon isn’t just presenting himself; he's presenting a carefully crafted image *of* himself, circulated and consumed as propaganda. Notice the elaborate drape. That fabric was purchased, labored over by weavers. Its presence is material statement, too. Editor: So, it’s less about the *art* of the portrait, and more about its production and the statement it makes about Napoleon’s power and status through those means? Curator: Precisely! We have to consider what its mass reproduction achieved in controlling his public image. Editor: That's fascinating, I hadn't considered the economics of photography in quite that way. Seeing the materials as a form of constructed messaging definitely shifts my understanding of it. Curator: Glad to offer a fresh perspective. Now you know what questions to ask next time you see a portrait of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.