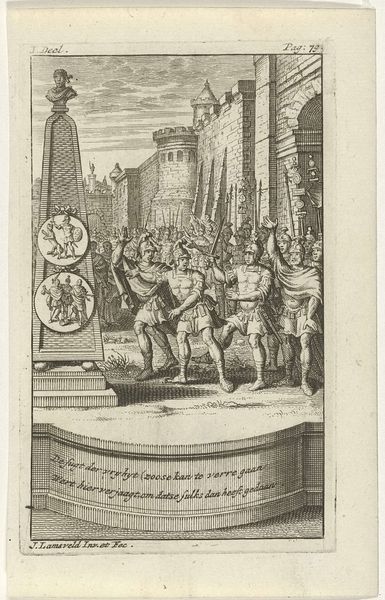

Leden van de senaatspartij zijn vastberaden om Julius Caesar te doden 1728

0:00

0:00

janlamsvelt

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Standing before us is a piece crafted by Jan Lamsvelt in 1728, titled "Leden van de senaatspartij zijn vastberaden om Julius Caesar te doden," or, "Members of the senate party are determined to kill Julius Caesar". This artwork, residing here at the Rijksmuseum, is an engraving, allowing for its wide distribution at the time. Editor: My first impression is one of stark austerity. The monochromatic palette and rigid figures create a sense of cold determination, even a kind of chilling resolve. You can see the lack of sentiment. Curator: Exactly. The imagery is directly connected to Roman iconography – the helmets, the architecture, the emphasis on civic duty, though twisted towards violence. The figures carrying their swords high reminds us how often symbols get repurposed in political struggle. What’s being expressed here in symbolic terms goes beyond simply the murder of Caesar. Editor: I see it as a brutal critique of political ambition and betrayal, especially as the figures, while seemingly united, lack any real sense of camaraderie. Their faces seem almost identical, suggesting perhaps that their individual identities have been subsumed by their shared purpose – a very dangerous kind of conformity that facilitates violence. Are we meant to identify with the conspirators or view them with suspicion? Curator: Consider that engravings, as printed media, were crucial for disseminating particular ideas to the populace. The clean, linear style suggests a deliberate construction of this historical moment for public consumption, maybe a call for resistance against powerful individuals that goes well beyond a reading of Julius Caesar. It uses Caesar's image and memory to signal an anxiety of authority. Editor: I completely agree. Placing this print within its 18th-century context is crucial. It prompts questions about whose story is being told and why. The act of illustrating and distributing the death of Caesar, isn’t a neutral act – it becomes a political intervention reflecting Lamsvelt's agenda. The artist also clearly alludes to gender roles; the focus here is on the power of male conspiracy and dominance in Roman political history. The almost hyper-masculine performance contributes to what one may critique today as the glorification of male power. Curator: Perhaps it's about the fear of tyranny in general and this work has been placed here as a reminder for future generations. Lamsvelt taps into deeply embedded visual codes associated with heroism and treachery. Editor: Looking at it through that lens, I think that both then and now it still stands as a chilling, very gendered warning against unchecked political power and the violence enacted in its name. Curator: It certainly gives one pause. The resonance of symbols across centuries, the ease with which they can be manipulated… it’s a disquieting reflection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.