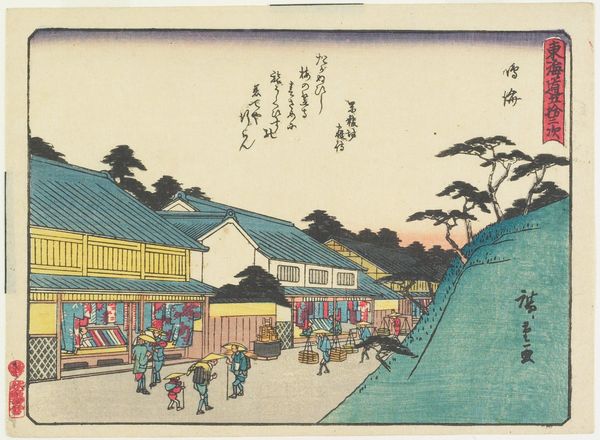

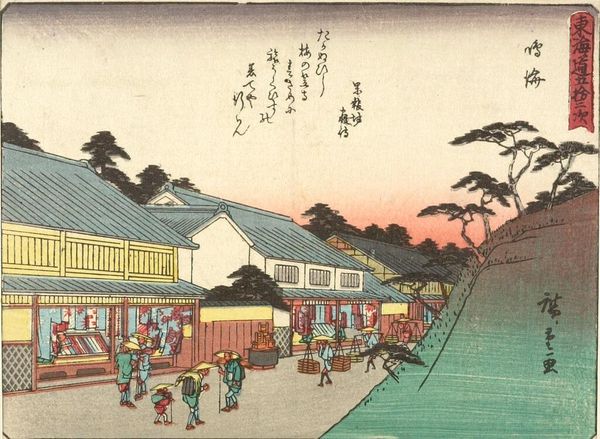

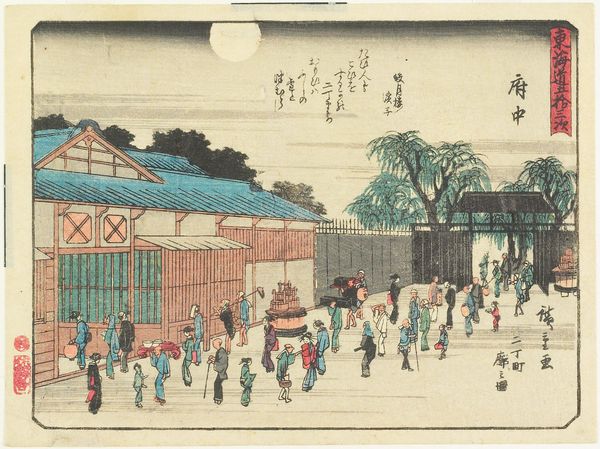

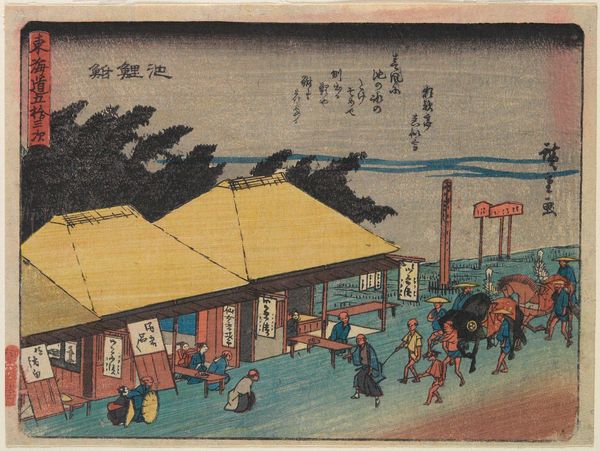

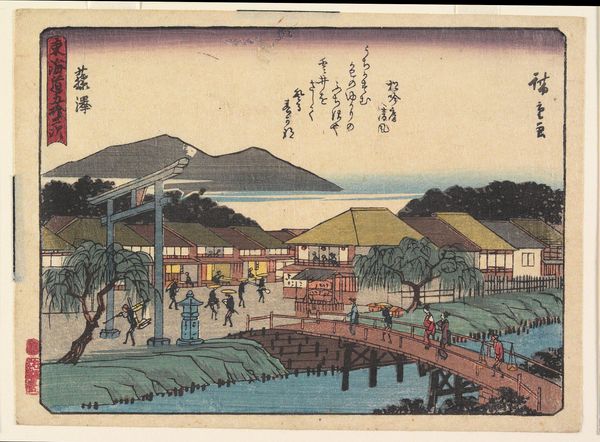

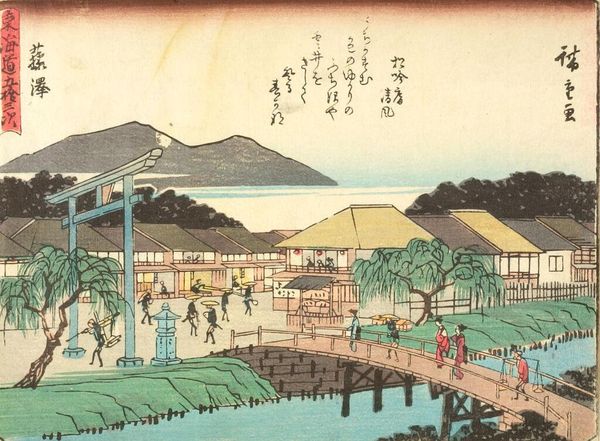

Dimensions: 6 1/8 x 8 1/4 in. (15.5 x 21 cm) (image)6 1/2 x 9 in. (16.5 x 22.8 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

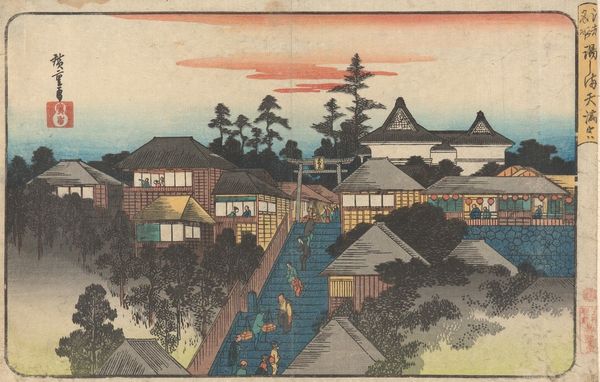

Curator: Let's explore this print, “Narumi,” by Utagawa Hiroshige, created around 1840 to 1842. It’s a woodblock print in the ukiyo-e tradition, currently residing here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: It has an intriguing feel—melancholic maybe? The cool blues of the buildings contrast so starkly with that warm, almost fiery sunset. I wonder about the physical process of carving all those lines… Curator: The interesting play of color and contrast reflects, perhaps, a deeper truth of 19th-century Japan, a society in transition. Consider the figures, common travelers. Hiroshige portrays them within the established societal hierarchies, even as the rising merchant class started gaining prominence. Their travel was often prescribed by class and trade. Editor: You see the rigid social structure, but I’m drawn to the laborers. The very act of carving each block would be so incredibly precise; each figure represents the countless artisans working to produce prints like this. Ukiyo-e wasn't just “art,” but rather commercial objects. And this example feels more down to earth, in contrast with the romantic depictions of courtesans, don’t you think? Curator: True, but even depictions of common people are stylized here to embody aesthetic ideals linked to gender and class, such as refinement and submission, depending on whether the individual is male or female. We can’t detach such concepts from understanding the representation of laborers and the broader implications embedded within it. The aesthetic doesn't erase those critical elements, in my opinion. Editor: I concede. We could endlessly debate whether form dictates social implications. But what's undeniable is the mastery displayed. Think of the different artisans—from block cutters to printers, each carefully imprinting the image and adding layers of meaning through the selection of color! Even the type of paper utilized would make the final expression ever so subtle. Curator: Yes, seeing how art reflects socio-economic conditions deepens my appreciation. The image invites dialogue, questioning norms of gender, race and identity in Edo-period Japan. Editor: Indeed. And seeing all that painstaking labor and all the many workers' involvement puts everything into an entirely different perspective for me, bringing us from art history to a labor dispute... food for thought, for sure!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.