Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

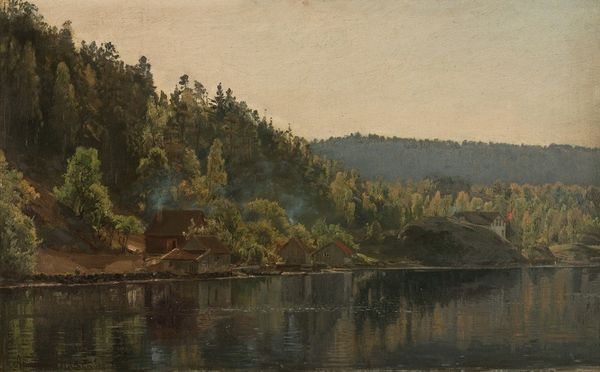

Editor: So, here we have Amaldus Nielsen’s "Tjern ved Rølland, Mandal," painted in 1873, using oil on canvas. There's a still, almost brooding quality to this landscape. The textures in the hills especially seem to pop out. What strikes you when you look at this? Curator: Well, let's think about the materiality of the paint itself. Notice the thickness and layering, especially in the hills you pointed out. This wasn’t just about representing a scene; it was about the *act* of painting. What does that act tell us about the artist's relationship to the land, and the process of production itself? Editor: Hmm, it suggests he was really immersed in the physicality of the place... the roughness of the terrain. Curator: Exactly. And think about who had access to these materials, and the means of exhibiting such a painting in 1873. Oil paint wasn’t cheap, and landscape painting was becoming increasingly popular among the bourgeoisie. Nielsen isn't just showing us a scene, he's participating in a whole system of art production and consumption tied to class. Editor: So the choice of materials and the landscape genre itself speak to a specific social context? Curator: Precisely. We see the labour and resources embedded in the canvas, the oil, even the way the artist applies the pigment. This piece then isn't merely representational, but part of an economic and social network. Editor: I hadn't considered how deeply connected materials are to broader social structures. I guess looking at the materials is a way to connect to what was available or trendy back then? Curator: Indeed. Thinking materially encourages us to move beyond the surface and interrogate the social and economic conditions that shape the work. What else do you notice? Editor: It definitely makes me appreciate it from a fresh angle. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.