photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

black and white photography

#

landscape

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

cityscape

#

monochrome

#

modernism

#

monochrome

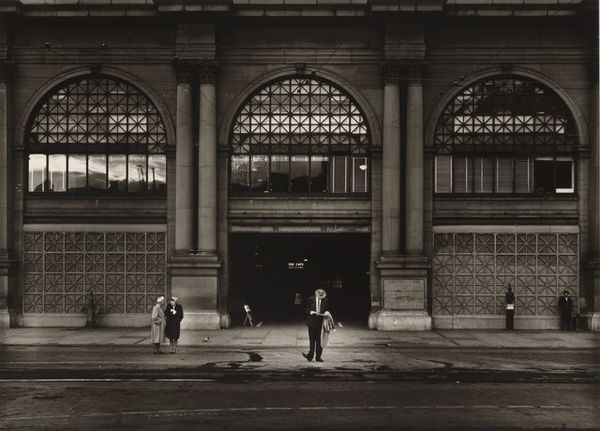

Dimensions: image: 22.9 × 34.5 cm (9 × 13 9/16 in.) sheet: 24 × 35.5 cm (9 7/16 × 14 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

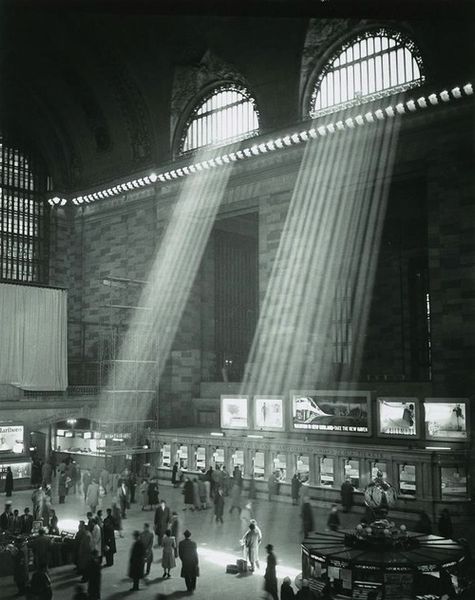

Editor: Here we have David Vestal's "Penn Station, New York," a gelatin-silver print from 1964. The way the light filters through those immense arches...it's stunning, but also makes me feel a little melancholic, perhaps due to its grand scale. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a lament, an elegy even, embedded in light and shadow. Look at those soaring arches—cathedral-like, almost religious in their aspiration. Vestal captures the soul of a monument just before its desecration, or, more accurately, a sacrifice. Consider how railway stations in this period functioned as gateways, thresholds to new beginnings, hope. Editor: Sacrifice? I hadn’t considered that. Curator: The old Penn Station wasn't just a transit hub, it was a symbol of civic pride and architectural ambition. By photographing it in 1964, just before its demolition, Vestal is, perhaps unconsciously, chronicling a profound cultural shift. Notice the almost ghostly figures populating the space. They appear to be caught between two worlds: the fading grandeur of the past and the sterile modernity that was to come. What stories do you think those commuters carry? Editor: That’s fascinating. I guess the image gains a new layer of meaning, knowing it captured a place right before it was lost. I hadn’t really thought about what a cultural symbol the station would have been at the time. Curator: Exactly! Vestal's photograph is not just about architecture; it is a meditation on time, memory, and the price of progress, it reminds us that physical structures often embody the intangible values we hold dear. Editor: I'll never look at black and white photography the same way. There's so much cultural information packed in the frame. Curator: Precisely. Understanding the context unlocks an emotional and historical landscape far beyond what’s immediately visible.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.