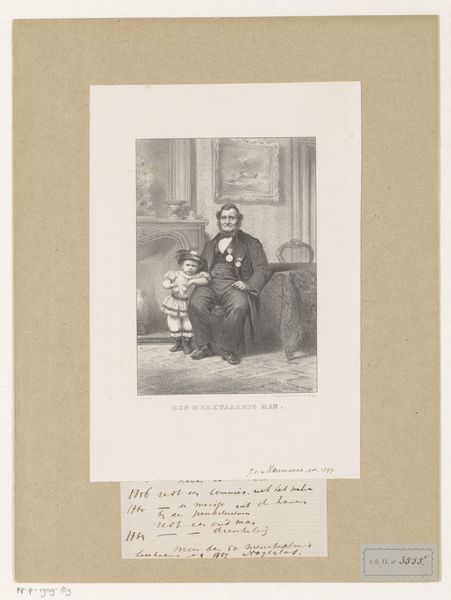

daguerreotype, photography

#

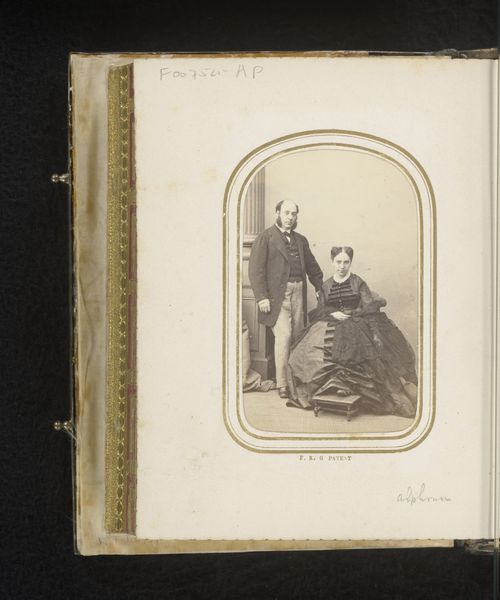

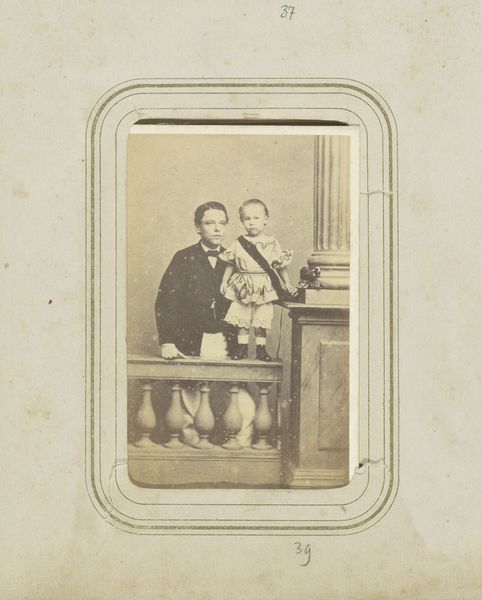

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

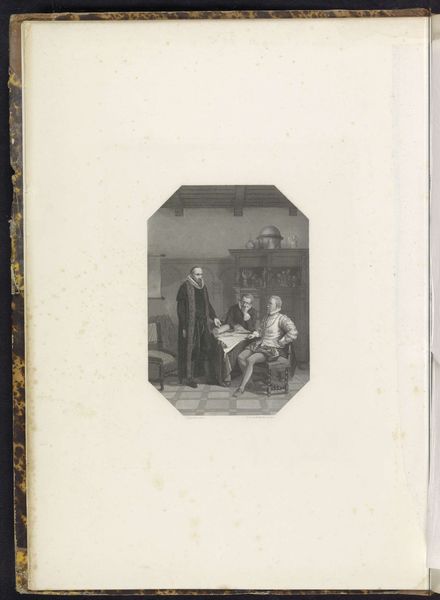

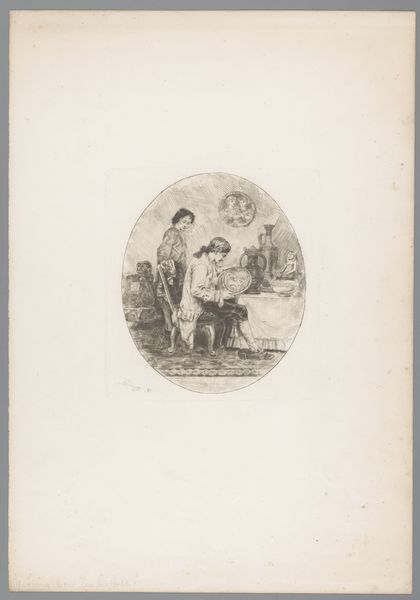

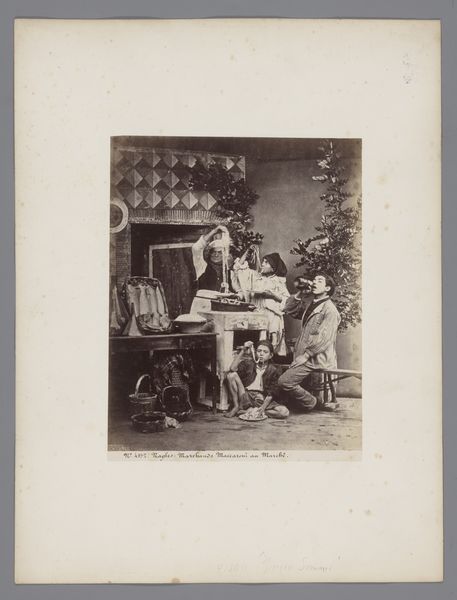

men

Dimensions: Image: 7 5/16 × 4 3/4 in. (18.6 × 12 cm); (a) Image: 8 in. × 5 1/4 in. (20.3 × 13.3 cm); (b) Mount: 14 7/16 × 10 5/16 in. (36.6 × 26.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This daguerreotype, attributed to Frederick Gutekunst, is titled "Dr. Joseph Parrish and an Idiot," created sometime between 1856 and 1860. It’s currently part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first reaction is unease. The lighting and the muted tones emphasize a starkness, almost a clinical observation. Curator: Well, let’s consider the period. This was a time when photography was both novel and seen as scientific documentation. Images like this often reflect the era's attitudes toward illness and disability, revealing more about societal perspectives than individual experiences. Editor: The balls—are they purely decorative, or do they signify something? I see the one held by Dr. Parrish resembles a globe, implying knowledge, power even. The young man, holding one to his ear, gives it an almost supplicant air. Perhaps representing intellectual yearning? Curator: It's plausible. Spheres have long carried connotations of perfection, totality. Here, the juxtaposition of these men with the globes hints at a commentary on knowledge and those deemed to lack it. It touches on the institutionalization of individuals labeled as "idiots," often based on questionable metrics. Editor: Right. So the photographic gaze itself becomes a tool of classification, reinforcing existing hierarchies. How did asylums utilize portraiture like this? Curator: Records like these would've been instrumental in patient management, case studies, and "scientific" investigations of mental conditions. These photographs became part of a visual taxonomy of the era. Editor: Fascinating—or rather, unsettling. I look at this now as an early form of objectification. It speaks to how photography contributed to shaping and reinforcing perceptions. Curator: It’s a powerful example of how art can act as a lens into historical power structures and beliefs. Even what may appear on the surface to be just documentation reflects deeply ingrained assumptions about difference and normalcy. Editor: So, the symbols themselves may seem inert but become profoundly meaningful within the context, loaded with ideology and institutional power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.