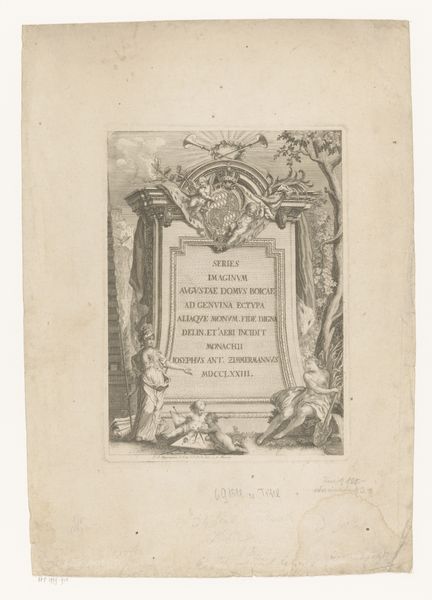

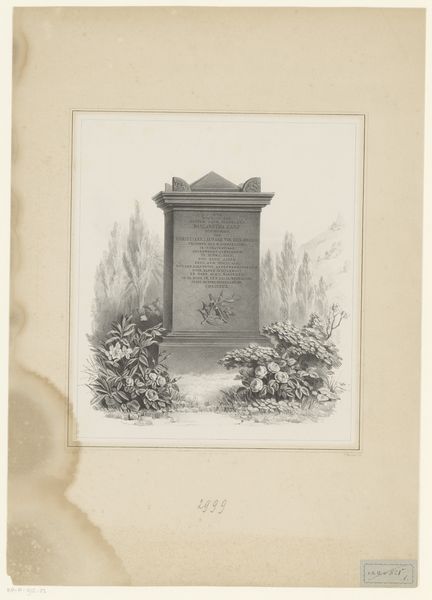

Passie van Christus naar ontwerp van Hans Holbein de Jongere 1784

0:00

0:00

christianvonmechel

Rijksmuseum

graphic-art, print, paper, engraving

#

graphic-art

#

neoclacissism

#

ink paper printed

#

parchment

# print

#

light coloured

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

form

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 262 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

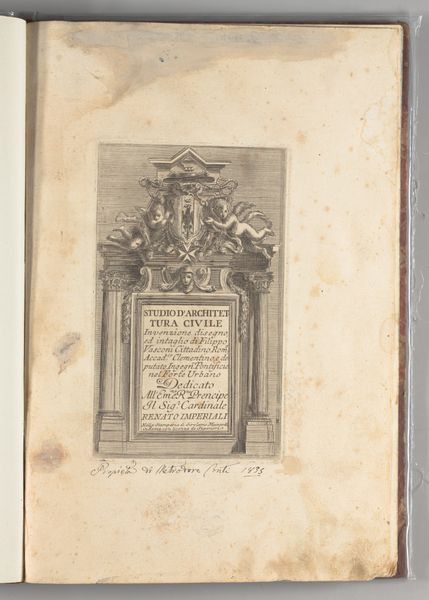

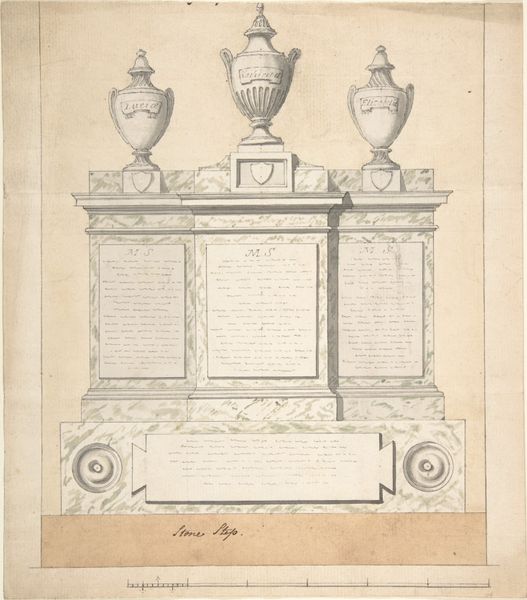

Curator: This engraving, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, presents a rather formal title page, “Passie van Christus naar ontwerp van Hans Holbein de Jongere,” dating back to 1784 and credited to Christian von Mechel. Its crafted with ink on paper, showcasing graphic artistry with some academic leanings and leaning into neoclassicism. Editor: It looks like an old, ornate tombstone, but much smaller and delicate. The two cherubs sitting on top don’t really soften its hard lines and solemnity, and they seem more like statues. It's very cool toned and gives the whole art piece a sombre vibe. Curator: I find the cherubs interesting! Here we see the common thread of integrating classical and Renaissance motifs into depictions of profound religious narratives. The garland seems to me like an indication of impending events and the suffering to follow. It invites the viewer into a deeper contemplation beyond the aesthetic, and is also about creating a bridge for contemporary understanding. Editor: Interesting. Given its context in the late 18th century, in Basel, one wonders what impact, if any, Enlightenment thought had in its production, publication and subsequent reception, when rationalism and religious belief were constantly under negotiation and challenge. Curator: What the Neoclassical style evokes for me is a sort of reasoned austerity—an effort to lend solemnity and importance. Also, remember, this is a graphic reproduction of what were already well known drawings from earlier. These accessible versions meant that broader society could have access to these kinds of artworks Editor: I do wonder what role this image played back in the 1780s. Perhaps there was a tension in Christian Mechel's Basle, as there was throughout Europe at the time, between Enlightenment thought, nascent modern secular society, and persisting power of institutional religion, like the Reformation legacy embedded in Holbein. I think about how prints helped disseminate ideas, visually. Curator: Yes, that is also another layer; the piece acts as a cultural object with an interplay between the form, subject, and broader societal forces shaping the creation and the reception. A neat object for considering memory! Editor: Indeed, from socio-historical to visual rhetoric, this print seems simple enough, but offers a surprising number of entry points into our European past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.