drawing, pencil

#

architectural sketch

#

drawing

#

quirky sketch

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

initial sketch

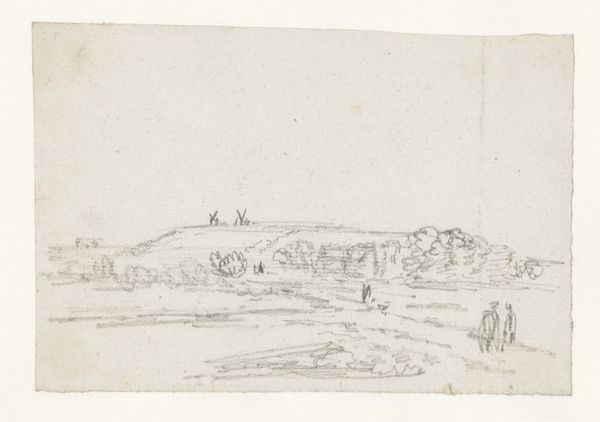

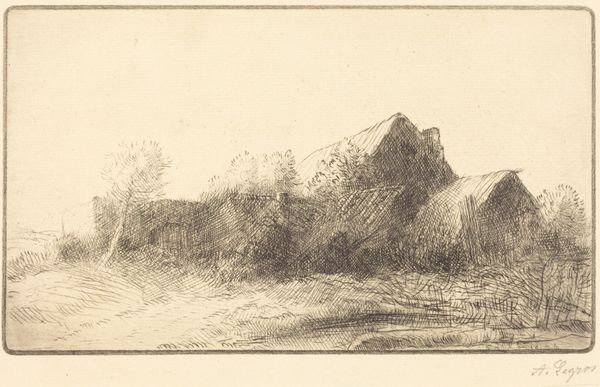

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 158 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re looking at a drawing by Andreas Schelfhout, titled "Sketch of a Landscape with a Ruin and Trees," likely created sometime between 1797 and 1870. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is melancholy. It’s washed in this delicate, almost mournful light, evoking a sense of abandonment, with a lonely figure near the ruins. It's small, subtle, with much empty space. Curator: Precisely. Schelfhout was a key figure in Dutch Romanticism, and he understood how to manipulate our perceptions of landscape. The ruins serve as a poignant symbol of time's relentless march, while also engaging the picturesque ideal—something that speaks to evolving class structures and an understanding of human impact on nature. The lone figure becomes a metaphor for human vulnerability within a landscape marked by history. Editor: And is the scale of the landscape itself then a representation of dominant patriarchal forces oppressing the individual? The figure is quite dwarfed. It suggests themes that resonate in modern dialogues surrounding individual agency within broader historical contexts. There’s an assertion that landscape and ruins become reflections of personal struggles—emotional states materialized in the external world. Curator: To broaden that, in 19th-century Dutch art, these landscapes held a public significance, helping construct and disseminate cultural identity. These drawings allowed artists like Schelfhout to translate observed locations into national symbols. The choice to include the figure provides a sense of perspective, but it may also represent a common observer who can identify with this view, in addition to serving religious themes. Editor: A valid point. It begs us to examine whose perspective is validated by representing this landscape. Does this idealized Romantic scene challenge or reinforce certain socio-political frameworks and assumptions related to privilege? Who, ultimately, does it include and exclude, in its celebration? And is the aestheticization of ruins—almost fetishizing decay—problematic when considered against the lives and conditions of the actual local communities and class? Curator: This piece definitely creates opportunities to discuss how cultural identity and national narratives have always been intricately linked to aesthetic representations and the art world, in ways that promote progress, however perceived. This pencil drawing continues to resonate because of its historical and contextual framework. Editor: Indeed, its ghostly impression persists through how we understand our relationships between individuals, narratives, and structures within landscape representations, even to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.