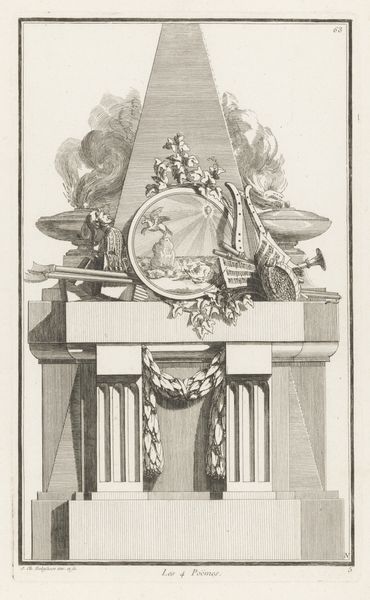

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 123 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

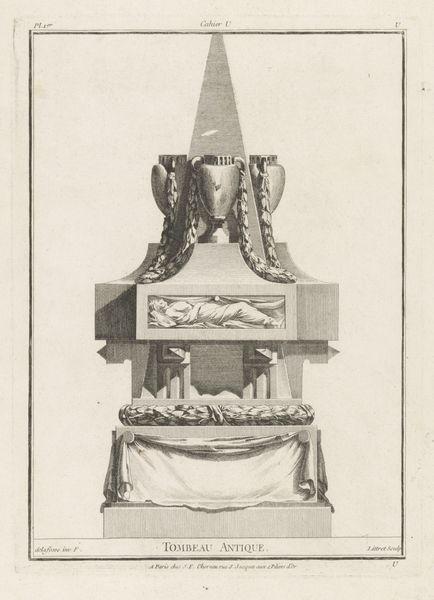

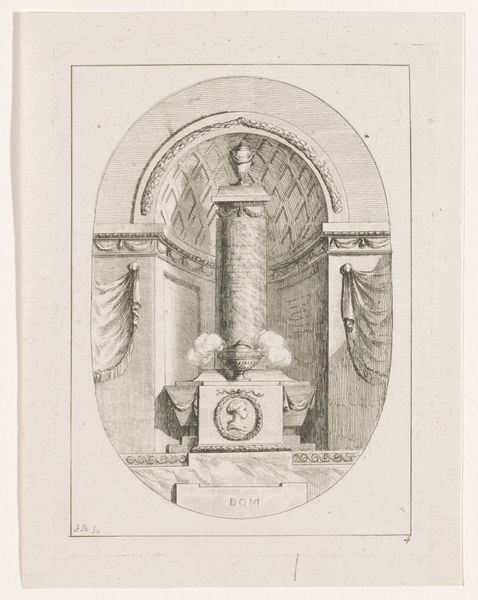

Curator: We’re looking at an engraving from the late 18th century, titled "Tombe op voetstuk" or "Tomb on a Pedestal," created by Juste Nathan Boucher. It’s held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It feels almost stark, in a way. So precise, a little cold, perhaps fitting given the subject matter. The level of detail in the engraving is impressive, considering. Curator: What interests me here is Boucher’s process. Look at the texture he achieves purely through line work, varying the pressure to suggest shadow and depth on the pedestal's stone surface. Think of the labor involved in each etched line, replicating a three-dimensional architectural form for print. The distribution networks alone meant the replication and distribution to potentially many, many viewers! Editor: Absolutely. And situating this within the social context, the rise of the merchant class in the 18th century saw elaborate tombs become statements of wealth and status, beyond the traditional aristocracy. "Tombe op voetstuk" becomes not just an artistic representation, but also evidence of the changing social structures of the era, echoing a fascination with mortality and memory and social elevation, perhaps even aspirations of social mobility. Curator: Precisely. These kinds of engravings played a crucial role in disseminating architectural trends and funerary design. Imagine workshops using them as guides for constructing actual memorials. There is such interplay of function, production, and aesthetic value that collapses distinctions between 'high' art and skilled craft. Editor: Considering that France was on the brink of revolution at the time this engraving was created, you can interpret this obsession with grand tombs almost as a counterpoint to the social unrest and impending upheaval, an almost anxious attempt at legacy building in uncertain times. I read an ambition of bourgeois patrons who try to insert themselves into narrative of social memory usually only accessible to monarchs. Curator: An interesting thought. I am compelled by the level of specialized labor demanded by printmaking. From the quality of the paper, the metal plates used for the engraving, all the way to the printing and distribution networks that made works like these accessible across geographical boundaries. Every element involved is significant, beyond Boucher’s artistic intention alone. Editor: Indeed. Ultimately, the image reminds us that representations of death are rarely just about death. They reflect society’s anxieties, ambitions, and ever-shifting power dynamics. Curator: A striking example of how printmaking mediates between material culture and social history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.