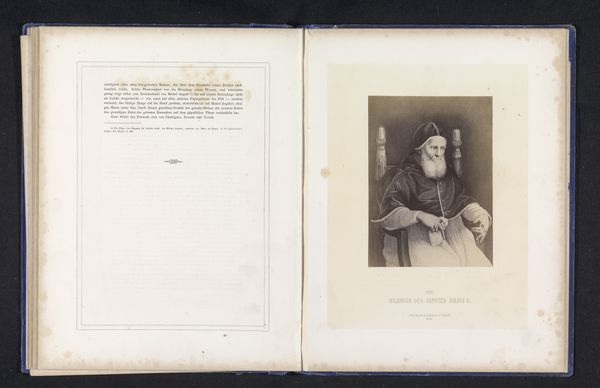

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij, voorstellende een portret van een oude vrouw before 1883

0:00

0:00

oil-paint

#

portrait

#

oil-paint

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

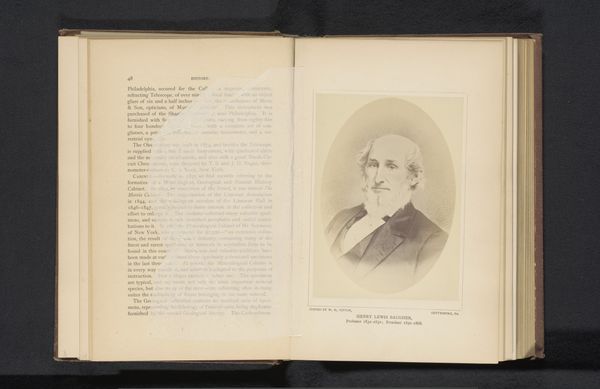

Curator: Let's examine this photogravure of a portrait painting, which, records indicate, was created before 1883. My initial impression is that this is quite tender rendering. Editor: It evokes a kind of humble solemnity, doesn’t it? The figure's aged face and hands seem burdened by experience. I’m drawn to the material contrast: delicate embroidery against her aged hands—a juxtaposition of luxury and labor perhaps. Curator: Precisely! Looking through the lens of social and cultural constructs, this piece reflects the gaze placed on older women, especially in the context of 19th-century European society. It brings up themes of aging, invisibility, and the way older women’s identities were, and still are, marginalized within society. The anonymity of the artist further complicates this reading; we don’t know who created either the painting or the photo-reproduction! Editor: Indeed. The reproduction process itself raises some intriguing points. Here we have a portrait—an intimate representation—made through layers of material processes, from oil paint to the photographic print. What gets lost and what’s amplified during the material and social labor of each copy? Also, how does the medium itself – photogravure – impact how the masses can consume the high art? Curator: Considering its historical context, this piece speaks to issues of representation. The shawl, for instance, might have socio-economic connotations— a mark of status or cultural belonging. The artist—whoever he or she was—might have been offering a silent commentary on these subtle class markers, too. Her wrinkled face and stooped shoulders, these were often left unremarked upon by portrait artists during that time. Editor: It also hints at the means of living. Think of all the steps: planting, milling, weaving. Who benefitted and who suffered at the creation of each product on display? What choices were forced on women laborers to subsist? I wonder about her connection to her garments: did she craft the flowers? Curator: I appreciate that you pushed us beyond merely the portrait, the subject, and its emotional qualities to see that social network. Considering her posture, the slight downcast of her eyes… it reads almost as an acknowledgment—if not an outright rebellion— against patriarchal standards of beauty, too. A silent power. Editor: Absolutely, and understanding the conditions that allowed art like this to exist allows us to consider more ethical frameworks when looking at work today. Curator: Examining her expression and considering the cultural narratives prevalent then offers new ways of engaging with discussions surrounding age, gender, and representation in art now. Editor: Indeed, there are many angles from which to discuss social practices, both past and present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.