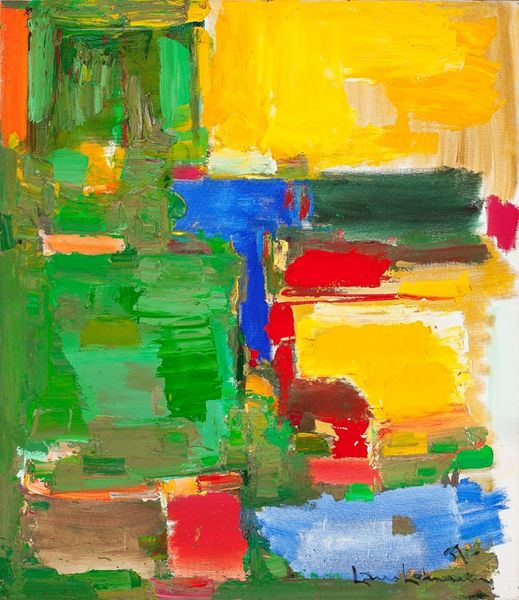

Copyright: Hans Hofmann,Fair Use

Editor: Hans Hofmann's "Landscape" from 1935, rendered in acrylic, strikes me as both chaotic and strangely serene. All of these vivid brushstrokes seem so raw and immediate. What strikes you most about Hofmann’s process here? Curator: I see Hofmann engaging directly with the materiality of paint itself. Look at the dripping passages—he’s allowing the paint to perform, to act according to its own physical properties. This rejects any illusion of depth in favor of celebrating the here and now of artistic labor and the visceral quality of applying pigment. Does the gesture emphasize speed or delay to your eye? Editor: Hmm, it almost seems contradictory—some areas are so fluid, dripping down the canvas, implying a quick action. Others look deliberate, almost sculpted, which would have required more time and careful manipulation of the acrylic paint. Curator: Precisely! And think about acrylic paint in 1935. It was still quite new. So, consider how Hofmann was investigating its properties, how he was quite literally pushing its limits. It also asks us to think about who had access to new materials, like this paint, during the Great Depression. This seemingly simple act of making becomes enmeshed in questions of material access. How does that context change your understanding? Editor: I hadn't considered that at all. Knowing it was made during the Depression changes things. It wasn’t just about aesthetic exploration but possibly a statement about access to resources, or even a meditation on simple means and nature? Curator: Exactly. And the vibrant colors. Where do those come from, materially speaking? Editor: I see what you mean! Pigments aren't just colors; they are also raw materials, often extracted from the earth or synthesized. I see now this “Landscape” embodies not just the image of nature, but its very substances, alongside the touch of the artist, shaping the landscape in pigment and time. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.