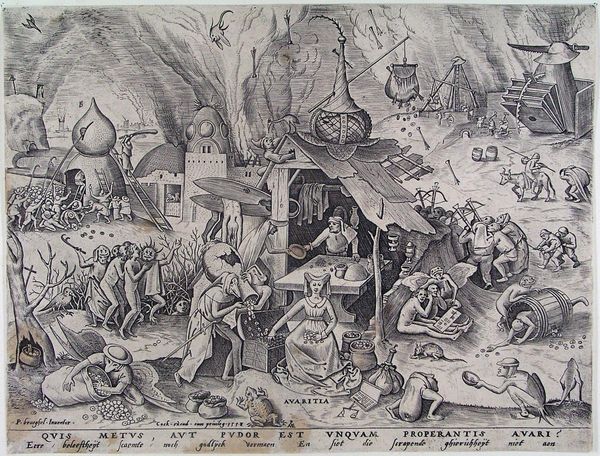

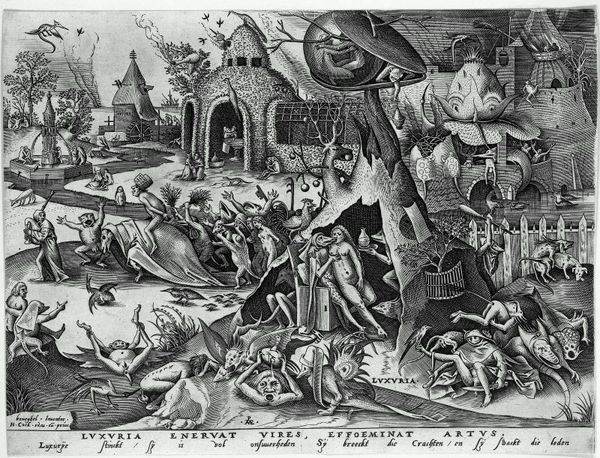

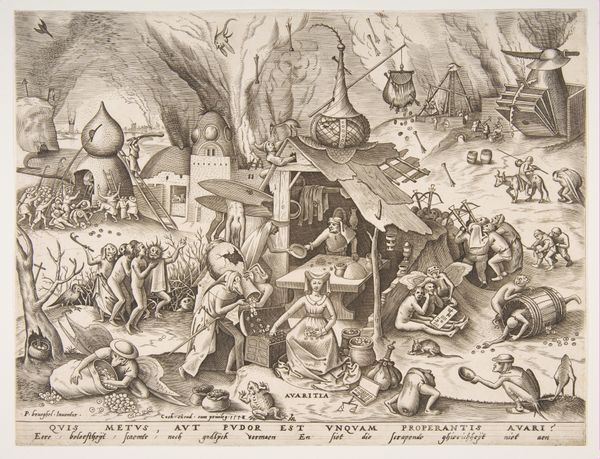

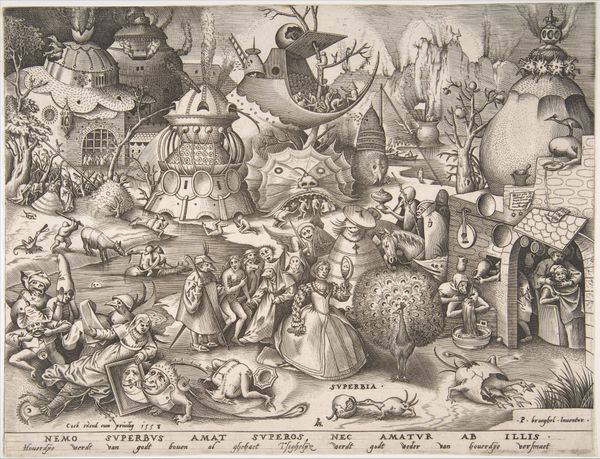

print, ink, engraving

#

ink drawing

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

christianity

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: Public domain

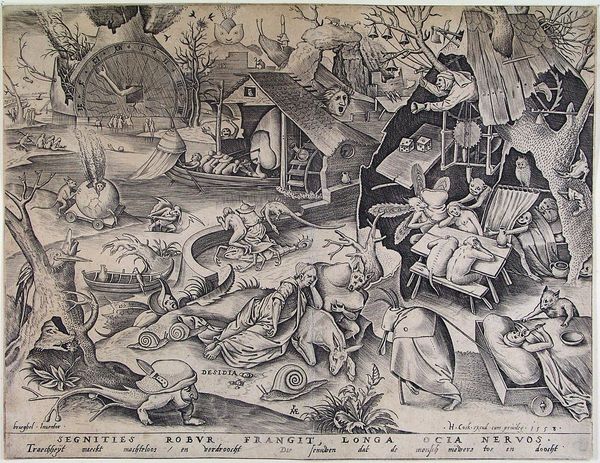

Curator: This intricately detailed print is Pieter Bruegel the Elder's "Envy," created around 1560. Bruegel, as always, offers a critical lens to his era, and the print exemplifies the complexities of Mannerist art. Editor: My immediate reaction? It's like peering into someone's darkest nightmare – a cacophony of unsettling figures and bizarre scenarios, all rendered in sharp, unforgiving lines. Curator: Absolutely. Bruegel masterfully visualizes envy not just as a personal failing, but as a destructive social force. The central female figure, Invidia, seems to be birthing monsters and inciting chaos all around. Note how her outstretched arms mirror a posture of aggression and incitement. Editor: The detail is incredible; every grotesque face, every distorted body speaks volumes. And look at how Bruegel uses symbols – the bag of money clutched by the reclining figure in the boat representing avarice, the pot of… limbs? A cauldron of malice, bubbling over. How does the choice of iconography reflect the broader anxieties about the societal order? Curator: That 'cauldron of malice', as you eloquently put it, connects directly to the socio-political context of 16th-century Europe. Bruegel critiqued the emergent mercantile class and religious hypocrisy, portraying a world driven by unchecked ambition and a desperate scramble for social status, with many losing their humanity. Even seemingly minor visual elements, like the burning building inside the monstrous head in the right background, signal the destructive capability of inner emotional torments. Editor: The image teems with hybrid creatures, half-human, half-beast, underscoring the dehumanizing effect of envy, maybe reflecting that the envious themselves become monstrous in their pursuit. The image evokes that sense of monstrous excess, and everything teeters on the edge of bursting. Is it about power structures – those who are envious of the elite? Curator: It functions both ways, because if one were to consider the religious implications, and its relationship to Catholic tradition, Bruegel addresses the disruption of social equilibrium, highlighting issues of inequitable systems with their subsequent ripple effects in that period. In this sense, "Envy" really acts as a mirror, holding up late-Renaissance society's ugliest truths. Editor: Well, it’s certainly an unsettling mirror, making me reflect on how even now, those symbolic forms retain an incredible psychological charge, evoking deep-seated fears about ourselves and society. Curator: Indeed, exploring “Envy” compels us to reconsider how the artist and his time regarded the intricate ties that hold society in an ambivalent dance between human desire and chaos.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.