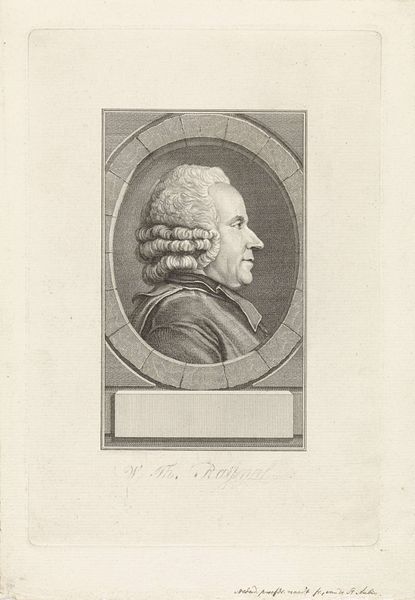

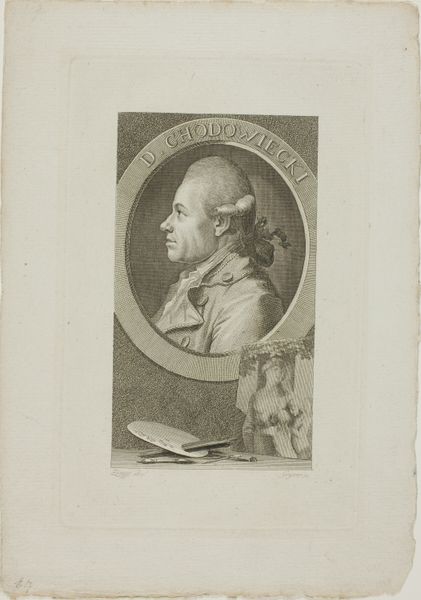

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 85 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

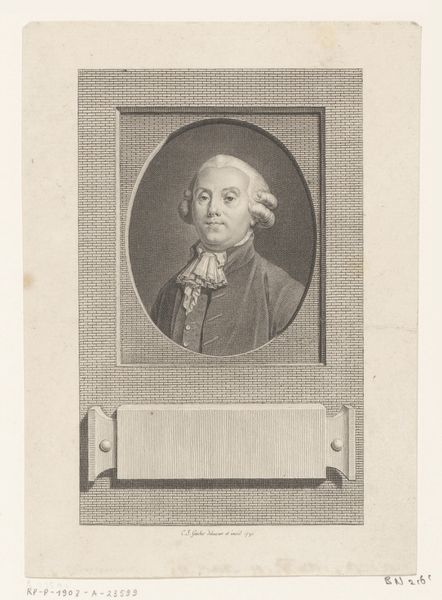

Curator: This is a portrait of Johann Georg Rosenberg, dating from 1749 to 1804. The artist is Gottlieb Leberecht Crusius, and the artwork is an engraving. What strikes you first? Editor: He seems intensely… proper. I get this overwhelming sense of powdered wigs, strict etiquette, and a general fear of messing up your shirt ruffles. Very neat, very contained. Curator: Well, engravings of this period were precisely about communicating status. The precision of the lines, the meticulous rendering of details, those are all signifiers. We’re talking about early capitalist society, a rising merchant class. How do you show you've "made it?" Commission a portrait. Editor: It feels impersonal, though. Less about capturing a person than presenting a brand, like an early form of PR. All that formality makes it hard to find any hint of the *real* Rosenberg behind the societal mask. Curator: It's also about production, and consumption. Consider the labor involved, the skilled craftsman transferring an image to a copper plate. Each print is then distributed and consumed. This availability challenges older aristocratic ideas of a singular artwork intended for private viewing by only the elite. This brings portraiture to a wider bourgeois public. Editor: The frame is clever – giving a sense of depth without feeling overtly showy. The profile view is almost scientific, objective... Like cataloging, "here is a specimen." Curator: Profiles were popular! They were affordable to produce and disseminate. The market value was much cheaper compared to painting with oil on a canvas. Demand determined production values, shaping accessibility and driving the aesthetic we now perceive. Editor: Even with the stiff formality, I can almost see a glint of humor in his eyes. Maybe it's just wishful thinking, or maybe that’s Crusius poking through the pretense. Curator: The medium makes the man, perhaps? Engravings facilitated a wider consumption of portraiture among the rising merchant class. This speaks to shifts in artistic labor and broader socio-economic trends. Editor: The experience changed my view a little. Initially it was stuffy and aloof, but considering its original context – as a sort of mass-produced status symbol – makes me rethink it all a bit. It’s an insight to 18th century anxieties about appearance. Curator: Absolutely. Art always acts a mirror to cultural currents. Understanding those flows provides context. Thanks for sharing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.